Theological and scriptural grounding

It is better to go to a house of mourning than to go to a house of feasting, for death is the destiny of every man; the living should take this to heart. (Ecclesiastes 7:2 NIV)

In addition to various individual factors or, as Worden calls them, mediators ofmourning (see 37-43), human reaction to loss is also determined by social variables (ibid. 43). Social frameworks

within which we operate, social roles we play, as well as religious subcultures “provide us with guidelines and rituals for behavior” (ibid. 44). Furthermore, religious teaching and the differing degrees of its internalization provide a person with either inner strength and support in times of loss and grief or with pain, disorientation and despair. The Christian Church offers its children the sustenance of hope and joy through its teaching of theology, anthropology, ontology, ecclesiology, and soteriology. In this paper I shall only briefly outline the main themes of Orthodox Christian teaching concerning death and dying, since each one of the aforementioned areas has been covered in great detail by the ancients and the moderns alike. In this brief exposé I will rely heavily on the work and teaching of Aleksei Osipov, a professor of theology at the Moscow Theological Academy, because he, in my opinion, though being a modern, carefully carries forth the treasure of

the teaching of the ancients.

within which we operate, social roles we play, as well as religious subcultures “provide us with guidelines and rituals for behavior” (ibid. 44). Furthermore, religious teaching and the differing degrees of its internalization provide a person with either inner strength and support in times of loss and grief or with pain, disorientation and despair. The Christian Church offers its children the sustenance of hope and joy through its teaching of theology, anthropology, ontology, ecclesiology, and soteriology. In this paper I shall only briefly outline the main themes of Orthodox Christian teaching concerning death and dying, since each one of the aforementioned areas has been covered in great detail by the ancients and the moderns alike. In this brief exposé I will rely heavily on the work and teaching of Aleksei Osipov, a professor of theology at the Moscow Theological Academy, because he, in my opinion, though being a modern, carefully carries forth the treasure of

the teaching of the ancients.

Theology

The core of Christianity is its belief in God. Moreover, it is a religious belief. One of the meanings of the word “religion” may be understood through the Latin word religō or repairing (re-) of the connection with God (-ligō). As Osipov shows in his work Put’ razuma v poiskah istiny (“The Path of Mind in Search of Truth”), not all beliefs are religious in nature.

Some of them hide real materialism and atheism behind a religious façade. In others, an overt mysticism is mixed with conscious and overt rebellion against God. Yet others… lack the very idea of the necessity of a spiritual connection between human and God. (112)

Christianity, on the other hand, is preoccupied with restoring of the lost connection, finding the lost Paradise, returning home like the prodigal son (Luke 15:17), or attaining salvation from bondage to decay (Rom. 8:21 NIV). Unlike other Christian denominations, Orthodoxy goes further than the restoration of iustitia originales and speaks of theosis, the potential of him or her who was created in the image of God (Gen. 1:27) to achieve the likeness of God (Gen. 1:26). Thus, the issue of proper theology becomes paramount to an Orthodox Christian. If we are to strive for the likeness of God, we must determine what He is like. In other words, as I mentioned in my paper τελοσ δε αγνειας υποθεσις θεολογιας,

[Orthodox] worldview is theocentric and the goodness is understood not in what God can give or save from, but in God [Himself]. In other words, “the measure of all things” in this world view is not the man, as Protagoras suggested, but God Who is the etalon, the fundamental principle of life. The ultimate goal in this case is not in acquiring good things that God bestows, but God Personself, or in the words of St. Seraphim of Sarov, “the acquisition of the Holy Spirit of God”; and since the God of Christian revelation is Love[3] (1 John 4:8), then acquisition of the Holy Spirit can be viewed as the acquisition of love and not only (or mainly not) as an action directed toward the person, but also as an action directed from the person. Of course, Christian revelation speaks about love as the highest human term that can be used, but there are certainly others: truth, purity, wisdom, righteousness, etc. All of these words, of course, cannot with any degree of adequacy describe God; and many of them lack precise definitions themselves. Who can give a precise definition to the word ‘love,’ for example? To say ‘love,’ however, is not to say nothing at all. Words like that give us the correct vector, point us in the right direction; for example: God is purity—not filth, God is truth—not falsehood, God is love—not hatred. (7-8)

In Life After Death in World Religions, Pendelhum tentatively attempts to define love through actions:

Acting out of love is acting for the good of others without asking whether they deserve it. (32)

It is, therefore, important to note that the death of a person is precisely the time when the action of the whole life, the force directed or vectored and applied, culminates: the person is at last united with the aspiration of his or her very being, reaches the destination to which he or she traveled for years and decades. This destination, seemingly different for different people, according to Christian beliefs is either toward God or away from God. The direction of this movement is determined by that which if often called the spirit of a person.

It is, therefore, important to note that the death of a person is precisely the time when the action of the whole life, the force directed or vectored and applied, culminates: the person is at last united with the aspiration of his or her very being, reaches the destination to which he or she traveled for years and decades. This destination, seemingly different for different people, according to Christian beliefs is either toward God or away from God. The direction of this movement is determined by that which if often called the spirit of a person.Anthropology

Christian teaching speaks of a human consisting of the “spirit, soul and body” (1 Thess. 5:23 NIV). While we do not hesitate in defining the body as the physical part of a human and the soul as “the innermost aspect of man, that which is greatest value in him” (Catechism of the Catholic Church 363), the spirit is not so easily defined. The same Catechism of the Catholic Church, for example, says that “’spirit’ signifies that from creation man is ordered to a supernatural end…” (367)—hardly a definition capable of settling anyone’s curiosity. In his lectures on Christian Anthropology, Osipov offers a more expanded view of the spirit. In my paper τελοσ δε αγνειας υποθεσις θεολογιας I give a brief synopsis of Osipov’s view as I understand it:

Of course, it is impossible to give an adequate definition of spirit. Firstly, it is because God is Spirit, that is to say the Spirit is the source, first cause, and the primary principle of all existence and, as is well known, primary elements do not have definitions.[4] Secondly, defining spirit we must necessarily place limits and draw boundaries for God, Who does not have limits or boundaries. However, I think it may be possible to talk about the qualities of the Spirit, especially as they relate to a human. I propose to accept the idea related by A.I. Osipov, and think about the spirit not as some sort of substance or “thin” matter, but as a vector, a direction, a goal of yearning. Therefore, a human spirit can be defined by that goal which the person ultimately wants to reach, the direction in which the person’s vector points. And if that ultimate goal is Goodness, that is to say God Who is the ultimate Goodness, then through this yearning for goodness, moving toward it, a person becomes like God, Who is not only the ultimate Goodness, but also is the ultimate movement toward goodness, or the vector that always points in one direction—goodness. (4-5)

This vector or human spirit, therefore, determines the destination of the last journey of the departed. Technically speaking, the only thing that really matters is the direction in which the vector of the human spirit is pointing at the time of death. However, just as the acceleration of an athlete determines the direction of the jump, so does the life of a person determines in which direction the vector will point (Osipov, O smerti [“On Death”]).

Thus, having been separated from the body, the soul either enters into the joy of her Lord (Matt. 25:21), or, having spent earthly life hiding from God (Gen. 3:8) and indulging in passions, the soul finds itself bound to the spirits of those passions which torment her and tear at her as hyenas tear at their prey. Those who have not set their vector on achieving the likeness of God, will not only be unable to unite with God, but “as smoke is blown away by the wind… [and] as wax melts before the fire” (Ps. 68:2 NIV) they will seek a place away from God’s Countenance and “go away into everlasting punishment” (Matt. 25:46 NIV). Yet fleeing they will be unable to flee from God’s presence because “through Him all things were made; without Him nothing was made that has been made” (John 1:3 NIV).

Ontology

All creation exists within God, the Source of all existence. In the words of St. Gregory Palamas:

God is and is called the nature of all that is in existence, for everything is in Him and exists because it is [in Him]… (qtd. in Osipov, Put razuma v poiskah istiny 369)

In other words, both the living and those whom we call departed are fundamentally in the same condition—they exist within the existence in God.[5] The difference is that the living are given time to come closer to God’s likeness or conform themselves more to God’s laws of existence, while the departed do not have such an option.

Likewise, the Scripture insists on the common existence of both the living and the departed and on their connection through God:

…even Moses showed that the dead rise, for he calls the Lord ‘the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob. He is not the God of the dead, but of the living, for to him all are alive. (Luke 20:37-38 NIV)

Ecclesiology

The connection between the living and the dead becomes even more clear within the context of Orthodox ecclesiology. According to Osipov, the Orthodox Church teaches of the organic connection between the living and the departed as members of Christ’s Body (O Tserkvi [“On the Church”]; cf. 1 Cor. 12:27). As in a human body, where an ailing member receives healthy blood and healing from the healthy members, the members of Christ’s Body are able to offer and receive help, healing and comfort through the living, organic connection (see Rom 12:4-5, 1 Cor. 12:12, ). Perhaps, it is this view of ecclesiology that has supported the ancient practice of offering prayers and sacrifices for the departed—a practice which otherwise makes little sense in purely anthropological studies.

Soteriology

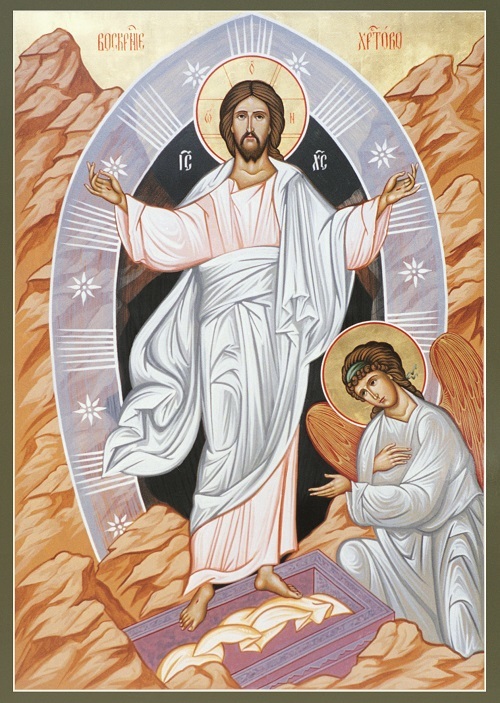

Thus, helping and comforting each other, both the living and the departed members of Christ’s Body can hope to attain salvation. According to Kuraev, Christianity teaches that having sinned, the first humans became ill with death and this illness is transmitted to all of their descendants (Vostok I Zapad [“East and West”]).. The task of salvation, therefore, is not merely in pronouncing that humans are forgiven—such a pronouncement is nice, but quite useless to those who are not only on death row, but also suffer from a terminal illness. In His salvific act, Christ not only declared the forgiveness of sins, but also offered a way to cure from the terminal illness: “Jesus answered, ‘I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.’” (John 14:6). As Pendelhum states in Life After Death in World Religions,

Christianity is unique among world’s religions in the nature of the claims it makes about its founder. He is seen not merely as a teacher or example, but as someone whose life and death are accorded a cosmic significance that holds the key to the cure of the deepest ills of the human condition. (31)

Through His incarnation, death and resurrection Christ offered salvation within his Body. Christ is the only One Who defeated death and the only One Who rose from the dead, thus, victory over death and the way to resurrection and life can be found only within Christ’s Body:

Once you were alienated from God and were enemies in your minds… But now he has reconciled you by Christ’s physical body… (Col. 1:21-22 NIV)

I am the living bread that came down from heaven. If anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever. This bread is my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world. (John 6:51 NIV)

Both the living and the departed, therefore, are receiving salvation and are able to offer and receive help and comfort, according to Orthodox teachings, through “His [Christ’s] Body, which is the Church” (Col. 1:24). Those members of the Body, who have not succeeded at fully rejecting their sinful passions, are still attached to them and tormented by them after they depart this life, are able to receive, however limited, comfort from the Church through prayers and other means. Being unable to repent after the death of the physical body, the reposed, through the prayers of the Church, are able to have strength and maintain hope of salvation. In the words of St. Epiphany of Cyprus:

Those who are living and are left (on the earth) believe that those who are dead and departed are not lacking existence, but are alive before God. As the holy Church teaches us to pray for our traveling brethren with faith and hope that the prayers are beneficial to them, the same must be understood about those who departed this world. (qtd. in St. John [Maximovich])

Communal scriptural and theological grounding

Give graciously to all the living; do not withhold kindness even from the dead. (Sirach 7:33 NRSV)

The Orthodox Church does not have strict theological definitions and explanations for why it adheres to the ancient practice of honoring the departed ones in prayer. The nature of our relationship with this millennia-long practice is well illustrated by the following episode from the life of St. Macarius of Alexandria:

St. Macarius of Alexandria once asked the angels who escorted him in the desert, “When the fathers were told to make offerings for the reposed in the church on the third, ninth, and fortieth day, what good does it do to the soul of the departed?” An angel answered, “God did not allow anything to be in the Church which is not good and useful; rather, He established heavenly and earthly Sacraments in His Church and commanded to do them.” (qtd. in St. Feofan)

The importance of the prayer for the departed is further supported by accounts such as the following:

Before the canonization of St. Theodosius of Chernigov (1896), a priest-monk … who changed vestments on the relics became tired and, sitting near the relics, he fell asleep and saw the saint, who appeared to him and said, “Thank you that you labor for me. I also ask you that when you serve the Liturgy, please remember my parents”; and he gave the names (priest Nikita and

Maria). Before this vision their names were unknown. A few years after the canonization, at the monastery where St. Theodosius had been the abbot, there was found his commemoration book, which confirmed these names and confirmed the truth of the vision. “How can you, a saint, ask for my prayers, when you yourself stand before the Heavenly Throne and give to people God’s grace?” asked the priest-monk, “Yes, this is true,–answered St. Theodosius,–but the offering at the Liturgy is more powerful than my prayers.” (qtd in St. John [Maximovich])

Maria). Before this vision their names were unknown. A few years after the canonization, at the monastery where St. Theodosius had been the abbot, there was found his commemoration book, which confirmed these names and confirmed the truth of the vision. “How can you, a saint, ask for my prayers, when you yourself stand before the Heavenly Throne and give to people God’s grace?” asked the priest-monk, “Yes, this is true,–answered St. Theodosius,–but the offering at the Liturgy is more powerful than my prayers.” (qtd in St. John [Maximovich])

Likewise, the theologians of the Church confirmed the importance of the prayer for the reposed:

One must not deny that the souls of the reposed receive comfort from the piety of the living, when the Sacrifice of the Mediator is offered for them or when alms are given in the church… (Blessed Augustine; qtd. in St. Filaret of Moscow)

Even if a sinner is departed, as much as we can, we must help: not by tears, but by prayers, supplications, and alms, and offerings. For these were not just thought up, nor is it in vain that we remember the departed in the Divine mysteries… but that from this they might receive some comfort. (St. John Chrysostom; qtd. in ibid.)

The Orthodox Church, therefore, continues to lift up Her prayers and bring offerings to the Holy Altar for the departed not only on the days described in the workshop section above, but also at every public service that is held in the church, on several special days throughout the year and especially during Great Lent. The Church does it not only for the benefit of the reposed, but also for the benefit and comfort of the bereaved, facilitating the grieving process and healing the broken hearts.

Rituals of the Church

The office of Holy Oil

Significance for the grieving and pastoral care opportunities: The grieving are encouraged to offer active prayer for the person who is suffering; the text of the service offers hope of recovery and end of suffering. The text of the service anticipates, works through and offers answers to some of the common questions that the bereaved may have: Why is the person suffering? What are the causes and reasons for suffering? What is the meaning of human life and human suffering? Can suffering end? How can we help? The grieving are guided through the process of making sense of the suffering of the loved one through Christian ontology and anthropology explored within the text of the service of Holy Unction.

Additionally, as priests (up to seven) are invited to perform the service, there is opportunity for counseling and the employment of the network of community resources. The service calls for 7 priests to get together at the bedside of the suffering person. Even in cities, where the concentration of churches and clergy is higher than in the country, the gathering of seven priests would represent several parishes. In the countryside, the priests gathered for the service may represent not only several parishes, but also more than one deanery. Even if the number of priests available to attend the service is smaller, which is usually the case in the Western American Diocese of the Russian Church abroad, several pastors gathered together not only represent the prayers of the larger Christian community on behalf of the afflicted, but also are able to offer their combined pastoral experience to benefit the family as well as a variety of community support services and other resources.

“O Physician and Helper of them that are suffering, O Redeemer and Savior of them that are in afflictions: Do Thou Thyself, O Master and Lord, grant healing unto Thine afflicted servant; show compassion, have mercy on him (her) who has grievously sinned, and deliver him (her), O Christ, from his (her) iniquities, that he (she) may glorify Thy divine power” (Kathisma hymn, Tone 4).

The office at the parting of the soul from the body

Significance for the grieving: The suffering person and the grieving family and friends are faced with the reality of the fast-approaching death. It is reminded over and over during the service that the time for death has come; instead of fighting the reality of death in their minds and hearts, the grieving are eased into the communal prayer of farewell. During these short moments before crossing the threshold, perhaps the most important moments of the whole life, the departing one and the grieving ones are encouraged to abandon the futile and atheist thrashing and fighting against the inevitable, and instead to concentrate their minds and spirits on the process of the passing, and to join together in a prayer of repentance, hope, and joyful anticipation of the motherly embrace of the Most Holy Theotokos, as the departing one passes. Through the gentle yet firm guidance of the prayers and as part of the community, the grieving are assisted in beginning to accomplish the first task of mourning—“to accept the reality of the loss” (Worden 27).

Quotes from the canon:

“Behold, the time for help! Behold, the time for protection! behold, O Sovereign Lady, the time for which, day and night, I fell down and warmly entreated thee” (from Ode 1).

“As the wings of a sanctified dove, stretch forth thy most-pure and all-honorable hands, and shelter me under their protection and shelter, O Sovereign Lady” (from Ode 4).

“Look down on me from above, O Mother of God, and mercifully attend now unto the visitation that has come upon me, that, gazing on thee, I may depart from thebody with rejoicing” (from Ode 6).

The office after the parting of the soul from body Main themes: prayers of the living for the peaceful repose of the departed; hope of the remission of sins and the future resurrection rooted in the love and compassion of Christ.

Significance for the grieving: At the time when the soul of the loved one has departed the body, when the grieving family and friends have lost any hope for a recovery of the afflicted one and the realization of the loss sets in with a sense of helplessness, the beautiful words of the church service invite the grieving to accept the reality of loss (Task 1 [Worden 27]), to begin working through the pain of grief (Task 2 [Worden 30]) in a guided way, and to begin to emotionally relocate the reposed (Task 4 [Worden 35]).

In inviting the grieving to actively participate in the prayer for the reposed, the Church gently guides them out of the sate of possible initial shock and despair which may be experienced at the time of death and into active realization of the reality of death through active participation in the supplications:

“I will pour out my prayer unto the Lord, and to him will I proclaim my sorrows. For my soul is filled with afflictions, and my life has drawn near to Hades. And like Jonah I will pray: Raise me up from corruption, O God.” (Ode 6 Irmos)

“Opening my lips, grant me a word to pray, O kindhearted Savior, for him (her) that has now departed, that he (she) find rest, O Master.” (Ode 1 Troparion )

“In the place of Thy rest, O Lord, where all Thy Saints repose, give rest also to the soul of Thy servant, for Thou lovest mankind.” (from litany)

“Again we pray for the repose of the soul of the servant of God, N., departed this life; and that he (she) may be pardoned all his (her) transgressions, both voluntary and involuntary.” (from litany)

After the initial rather short service, the grieving have time to continue working through the pain of loss in a variety of ways: by lovingly preparing the body of the departed one for burial, by taking turns reading the Psalter, and by taking some quiet time to rest, contemplate, pray, cry, or give and receive comforting.

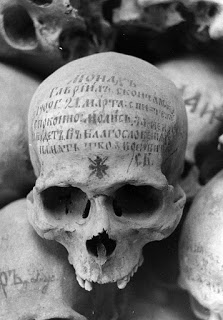

The preparation of the body and the reading of the Psalter Details (see The Great Book of Needs 3:110-112): The body is washed with water (bodies of priests and bishops are anointed with oil), dressed and placed in the coffin. The washing of the body is a practice common to various religions and was apparently inherited by the Christian Church from Judaism. Already in Acts 9:36-37 we can see a mention of the washing of the body of a reposed Christian woman by those who were close to her. The body is kept in the house for 1-3 days and then it is taken to the church for burial services. Sometimes a shroud is used in place of a coffin, but in Russia a wooden coffin is traditionally used along with the shroud. Men serve men and women serve women in preparing the body for burial. The Psalter for laymen or Gospel for priest or bishop is read continually until the burial.

Significance for the grieving: The grieving are guided to further acceptance of the reality of death through the preparation and handling of the body. The physical contact with the body of the loved one not only provides a very tangible way of working through the first Task of Grieving (Worden 27), but also helps comfort the bereaved by giving them an active role in the taking care of the loved one even after his or her death. This ability to actually do something for the benefit of the reposed, may help deal with the feeling of guilt by the bereaved, which appears to be common among the surviving family and friends (see Worden 59-60). The last acts of taking care of the body of the loved one may provide the grieving family and friends with an outlet for their love and affection and a way that their desire to do something for the reposed one may be realized in a very tangible and physical way. The very communal nature of the task, the involvement of many family members, on the other hand, provides for the ministering to those who are overtaken by emotions and feelings of loss.

The changing of the environment in which the reposed is missing through symbolic actions, such as the covering of the mirrors helps avoid the so-called “’mummification,’ that is retaining possessions of the deceased’s in a mummified condition ready for use when he or she returns” (Worden 28), which often points to “denying the facts of loss” by the bereaved (see ibid.). Often a photograph of the departed one is displayed in a visible place and a black ribbon is placed across the bottom corner to denote the repose.

Further work through the pain of grief is facilitated through the reading or hearing the Psalms. The grieving may readily identify with the intense emotions of distress and despair as depicted in some psalms and be gently guided to hope of healing and resurrection as the psalm-singer reflects on God’s help and love for His people.

The all-night vigil for the departed

Significance for the grieving: The vigil is the beginning of the burial service. The body leaves the house and is left at the church overnight, which facilitates the early stages of Task IV of the mourning process by shifting the focus from the family of the reposed to the whole community. After the intense hours and days of the loss being the family’s loss and the reposed being the departed member of the family, a symbolic transformation takes place, in which the loss becomes that of the community and the reposed becomes the departed member of the said community. The entire community joins in prayer for the departed, thus helping the closest family members and friends to begin “to emotionally relocate the deceased and move on with life” (Worden 35). Thus, the bereaved symbolically give the reposed one to the community and join the community in prayers and psalmody. Further opportunities for ministering to the grieving are afforded to the clergy and the community members.

Quotes: “For the sake of the holy sufferings which Thou didst endure for the sake of the faithful, O Christ, give rest unto him (her) that has fallen asleep in the hope of life eternal with the Saints.” (Apostikha of Tone 2)

“The souls of the righteous are in the hands of God, and no torment will ever touch them. In the eyes of the foolish they seem to have died, and their departure was thought to be an affliction, and their going from us to be their destruction; but they are at peace.” (Wisdom of Solomon 3:1-3 NRSV)

“For Thou art the Resurrection, and the life, and the repose of Thy departed servant, N., O Christ, and unto Thee do we send up glory, together with Thy Father Who is without beginning, and Thy Most-holy, Good and Life-giving Spirit, now and ever, and unto the ages of ages.” (Exclamation)

The Liturgy and the burial

Significance for the grieving: The final stages of the earthly presence of the departed happen in a communal setting and are adorned with ritual. Prayers of hope and resurrection are offered by the community as well as prayers for the grieving. The burial takes place immediately after the Liturgy; the funeral service may also be performed separately from the Liturgy. The highly ritualized “last kiss” just before the casket lid is closed seals the process of seeing the reposed one depart and provides a tangible symbol of closure for the grieving. The casket lid is closed in the presence of the family and friends, and the grieving carry or accompany the body to the gravesite. This procession, of course, is reminiscent of seeing the loved one off to a long journey, when family and friends would walk with him or her for a while to a symbolic threshold. The sense of closure is further developed at the gravesite where, after lowering the casket into the grave, each person present puts a certain amount of dirt into the grave, thus “sealing” the grave and ritually acting out the emotional closure which is to take place. The honor of throwing the first handful or spadeful of dirt into the grave is usually given to those closest to the reposed.

The commemorations (3, 9, 40-day, anniversary of death)

The commemorations on the third, ninth, fortieth day after death and on anniversaries thereafter are one of the most ancient Christian practices and have been observed for most of the history of Christianity. Already the Apostolic Constitutions, a fourth-century document, refers to those commemorations as an “ancient pattern”:

“Let the third day of the departed be celebrated with psalms, and lessons, and prayers, on account of Him who arose within the space of three days; and let the ninth day be celebrated in remembrance of the living, and of the departed; and the fortieth day according to the ancient pattern: for so did the people lament Moses, and the anniversary day in memory of him.” (Apostolic Constitutions 8:42; ANF 7:498)

Significance for the grieving: As Worden mentions, the funeral services are conducted very close to the day of the loss, and “often the immediate family members are in a dazed or numb condition and the service does not have the positive psychological impact that it might have” (79). Through the ancient “3-9-40” pattern, the community gets an opportunity to observe the grieving and offer further support and healing as needed. Likewise, the grieving are offered an active approach to expressing their grief through prayer and participation in communal services. The services, through communal theology, ontology and ecclesiology, offer a spiritual link with the reposed and hope for continued life, thus battling the extreme feelings of irreversible loss. The reposed is mentally and emotionally relocated as he or she is thought of as following through the stages of afterlife. Yet a link between the departed and those who remain is retained through communal ecclesiology, in which there is an organic connection between the living and the reposed. Through pastoral applications, this link is allowed to achieve a unique degree of intensity which depends on each individual: from the most intense and personal to merely a formal one for those who need more space.

Pastoral applications, areas of future development and conclusions

Do not avoid those who weep, but mourn with those who mourn. (Sirach 7:34 NRSV)

Writing about the pastoral applications of church services and their role in the grieving process, Bishop Athanasius (Sakharov) writes:

The Holy Church does not stop our tears for the reposed. On the contrary, in certain instances She urges us to cry, for this is the natural outlet for grief, a comfort for the heart. Into the mouth of the dying one She puts a request, “my relatives in the flesh, and my brethren in the spirit, and my acquaintances, CRY, sigh, wail: for now I am leaving you.” Immediately, She repeats this request at the time of the last kiss as if from the reposed, “Seeing me speechless and breathless lying before you, cry for me, brethren and friends, relatives and acquaintances.” And from herself She urges those around the casket, “we are all shedding tears when we see the lying corps, and [we] approach to kiss and to say: behold, you have left those who love you and you do not speak with us anymore, friend.”

The words of the services present a validation for a natural human response to grief, supporting the feelings of the bereaved and offering the pastor a unique opportunity to learn the skills of caretaking from the wisdom of the generations of Christians and Christ Himself:

… Jesus began to weep (Jn 11:35). Not only did Jesus make himself the model of compassion for all those who mourn but in his own Gethsemane, recognizing his own human need for the compassionate presence of others, he asks his friends to stay with him in the garden. (Roussell 56)

Far from being preoccupied exclusively with the fate of the departed, the Church takes care of the grieving through its services and rituals. In the sections above, I have examined some elements of church services and rituals in their connection with facilitating the grieving process as well as some aspects of Orthodox teachings as they pertain to death and dying. It appears that in the combination of rituals and teaching the Church offers a treasure chest of effective tools for a pastor to be able to offer help to the bereaved. But in order to use these tools effectively a pastor must not only be proficient in theology, but also in psychology and sociology, especially as these disciplines relate to the process of grieving. The task of educating a pastor within the Russian Church abroad if further complicated by the multicultural dimensions within the Russian community in the U.S. As Rosenblatt points out in Ethnic Variations in Dying, Death, and Grief: Diversity and Universality, “across cultures, people may differ in what they believe and understand about life and death, what they feel, what elicits those feelings, the perceived implications of those feelings, the ways they express those feelings, the appropriateness of certain feelings, and the techniques for dealing with feelings that cannot be directly expressed” (18). The reality is this observation may be experienced within a Russian-speaking community in the U.S. which consists of members who belong to different age groups and immigrant generations, who come from different regions of the former Soviet Union and varying socio-economic backgrounds, display vastly different degrees of linguistic and cultural assimilation into the American society, and whose understanding of Orthodox theology varies from below negligible to very good. All of these factors make the task of a pastor more challenging and rewarding as the pastor operates on multiple cultural levels to meet the needs of his parishioners.

In closing, I should like to share a quote, which, in my opinion, best summarizes the challenges that pastors face and the direction in which they should develop their pastoral skills in caring for the bereaved and the grieving:

Grief and bereavement ministry challenge us to view life and its limitations realistically. In the context of a personal, dynamic and (w)holistic approach, care providers are asked to reflect on their own personal and professional ways of coping with loss and grief. To view all aspects of one’s life—with its shadows, vulnerabilities, weaknesses, possibilities, skills and strengths—opens one to a high degree of empathy for the suffering of others and facilitates quality personal and professional caregiving. (Roussell 3)