The third installment of the talk on iconography with Father Sergious, the head of the icon-painting studio and icon painting school at St. Elisabeth Convent:

The third installment of the talk on iconography with Father Sergious, the head of the icon-painting studio and icon painting school at St. Elisabeth Convent:

Some of the ancient images and monuments that have reached our time are dated around the fifth century and include the Crucifix on the panel of the doors of the Basilica of Saint Sabina in Rome and on a tablet in the British Museum. Let us take the panel on the doors of Saint Sabina. We are not accustomed to seeing such imagery as we are used to seeing crucifixion in its completed and canonical form. A form with was developed over centuries. However, this panel depicts an image of three people with the two thieves and Christ in the

center. Here we do not see any traces of the cross itself. The image of the cross is implied from the position of the arms and the figures of the people who are crucified.

The central figure is clearly larger than the other two but at the same time, there is no halo and no inscription, which would confirm that

it is Christ. If we look strictly at the physical appearance of the central image, we can see features that closely resemble Christ, including long hair and a beard. Here, all the figures are bare, wearing only a breechclout. This scene is quite concise, as we do not see the dogmatic teachings of the church, the image does not tell us an in depth and commonly acceptable explanation of the event. It appears to be limited and compressed and cab be viewed more as a symbol that reminds us of something we know rather than an image or picture.

The initial appearance of the cross as a symbol came quite late in relation to the history of Christianity. It is generally associated with the vision of Emperor Constantine (4th Century) before a deciding battle. The Emperor saw a particular sign in the sky. It resembled a cross with interconnecting letters “X” and “P” and heard a voice saying, “In this sign conquer”. The next day he advanced with the sign that portrayed the cross from his vision and came out victorious while being heavily outmatched. The symbol was not forgotten and was commonly used since the miraculous event.

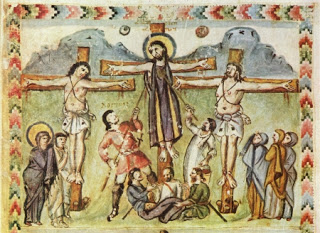

Here is another interesting version of the crucifixion scene with biblical references. On the right, we see the crucified Christ and on the left – the death of Judas. Below him, there is a bag with the pieces of silver. However according to the scripture, Judas returned the thirty pieces of silver by throwing them at the feet of the elders in the temple. Here, the main purpose of the bag with silver coins is to identify Judas to the viewer. Turn

Here is another interesting version of the crucifixion scene with biblical references. On the right, we see the crucified Christ and on the left – the death of Judas. Below him, there is a bag with the pieces of silver. However according to the scripture, Judas returned the thirty pieces of silver by throwing them at the feet of the elders in the temple. Here, the main purpose of the bag with silver coins is to identify Judas to the viewer. Turnyour attention to the parallel of the two trees. The first tree is the cross, on which Christ is crucified. It symbolizes the tree of life. The other tree is the tree of death because by taking his own earthly life, Judas is sentencing himself to eternal death and suffereing. Christ is shown here in an interesting manner. His body resembles the shape of the cross with the arms and legs at a straight angle, which makes it, seem as if He is floating in the air. The image also does not seem to portray him suffering physically; his eyes are open, and the sign above him says “King of Glory”. It is unclear if the image is depicting His death or birth. Once again, there is no mention of the suffering or death that is seen in contemporary

iconography.

Another symbolic image of the cross is that same “chrism” that appeared to Emperor Constantine. It is crowned with a laurel wreath as a symbol of victory. On the image we see the cross itself, two soldiers guarding Him, two birds and the wreath on top. Although the image does not show Christ, but at the same time it symbolically points to Him.

Another symbolic image of the cross is that same “chrism” that appeared to Emperor Constantine. It is crowned with a laurel wreath as a symbol of victory. On the image we see the cross itself, two soldiers guarding Him, two birds and the wreath on top. Although the image does not show Christ, but at the same time it symbolically points to Him.

In Ravenna, inside the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare in Classe we can find a certain Cross. Which biblical event do you think is depicted there? The event is the Transfiguration of our Lord. In the center, Christ is on the cross engulfed in mandorla, which is an almond-shaped aureole of light surrounding the entire figure of a holy person. Moses and Elijah surround him and the sheep represent the apostles.

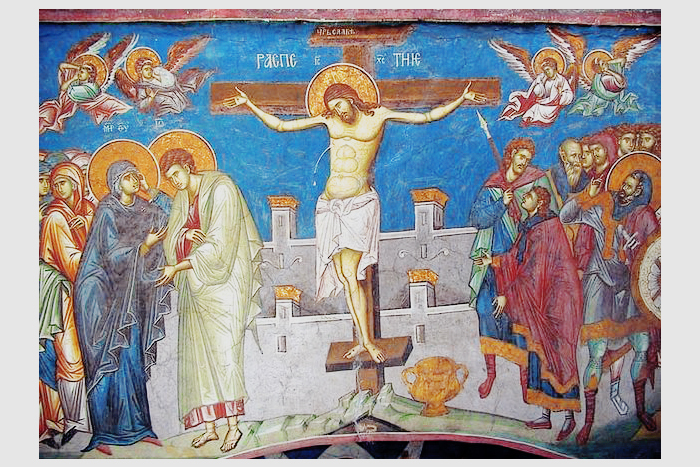

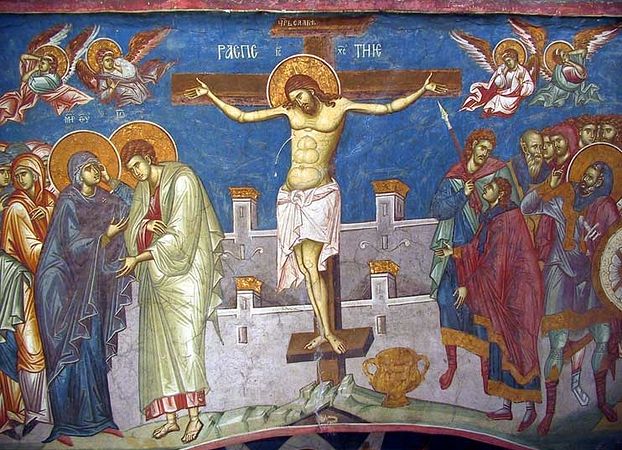

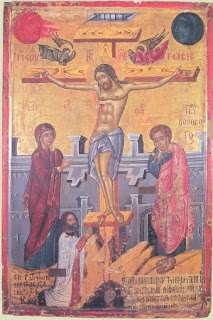

Next, we come across the first image that explicitly and in detail illustrates the text from the Gospel. Here we can see three figures and first turn our

attention to the way the thieves are depicted. While we rarely see them in contemporary iconography, in the past their imagery was very important and should not be overlooked today either because the thieves symbolize us. Underneath the Cross, we see the three soldiers that are dividing the robes of Christ among themselves, the Myrrh-bearing women, Saint John the Theologian and the Mother of God. If we look closer, we can notice a silent dialogue between Christ and the thieves.

Christ turned to the wise thief, who is pictured to right of Him. In turn, the wise thief has his head lowered, which signifies repentance. The sun and the moon, pictured on the top corners, point to the cosmic reality of the event that is occurring. They indicate that nature in its entirety is present, as if it has stopped in the eternity, and it is not just an execution on a certain day. Using the imagery of the heavenly bodies the iconographer also attempts to demonstrate the “reaction” of nature towards the crucifixion, basing their conclusion on the scriptures in which the evangelists mention the events that occurred between the sixth and until the ninth hour. (Mathew 27:45; Mark 15:33; Luke 23: 44-45)

Christ turned to the wise thief, who is pictured to right of Him. In turn, the wise thief has his head lowered, which signifies repentance. The sun and the moon, pictured on the top corners, point to the cosmic reality of the event that is occurring. They indicate that nature in its entirety is present, as if it has stopped in the eternity, and it is not just an execution on a certain day. Using the imagery of the heavenly bodies the iconographer also attempts to demonstrate the “reaction” of nature towards the crucifixion, basing their conclusion on the scriptures in which the evangelists mention the events that occurred between the sixth and until the ninth hour. (Mathew 27:45; Mark 15:33; Luke 23: 44-45)

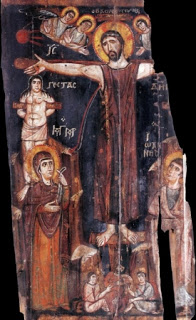

By studying the icon of the crucifixion dated around the 8th century from the monastery of Saint Catherine, we can notice that the thieves are distanced further in the background. We can also read their names – Gestas and Dismas. Here, Christ is pictured in a long chiton without sleeves. Although in reality people were executed without clothing, here the chiton symbolizes the kings glory. Generally, in eastern iconography it is very rare that the Lord is depicted in this scene without the crown of thorns. However, this particular icon is an exception because, according to the Gospel, the crown of thorns was taken off His head before He was crucified.

We can also see the Mother of God and Saint John the Theologian. Starting from this time period a tradition has already developed to depict the Mother of God to the right of Christ and Saint John on the left side. As they look directly at Christ and the ongoing event, they symbolize all of humanity. It is also worth mentioning that the icon is one of the first to show Christ with His eyes closed. This means that the icon shows that He has passed away and “given His life for His sheep”, although the position of his body is still quite straight. Here we can see the deep dogmatic meaning related to our salvation. Christ is not just a man. He is both man and God. Inexplicably, He has two distinct natures Devine and human. So how can someone who is both fully man and fully God die? Death cannot approach God. Even in one of the verses sung on Great Friday, we hear the words “how can Life die?” as even the church marvels and cannot logically; in human terms begin to explain how this could have happened. Therefore, this mystery engulfs us through this particular icon and here amidst it all we see its central idea and purpose.

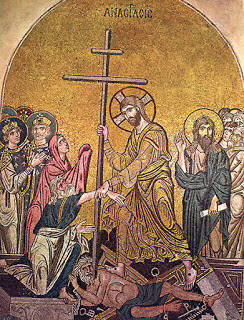

The icon of Resurrection also has a cross, but this cross processes a different meaning: The Lord descends into hades, takes Adam by the hand and brakes the gates of hell with the cross. Within this image lies the meaning of the crucifixion. The cross is not only an instrument on which Christ was crucified as a man but more importantly it is a weapon with which along with His death Christ: “Trampled down death by death”.

The icon of Resurrection also has a cross, but this cross processes a different meaning: The Lord descends into hades, takes Adam by the hand and brakes the gates of hell with the cross. Within this image lies the meaning of the crucifixion. The cross is not only an instrument on which Christ was crucified as a man but more importantly it is a weapon with which along with His death Christ: “Trampled down death by death”.