The events of Good Friday develop with lightning speed. The central theme of Good Friday, the theme of death, is being experienced through this chain of events: the crucifixion of the Lord, his death on the cross, his deposition from the cross, mourning and laying Jesus in the coffin.

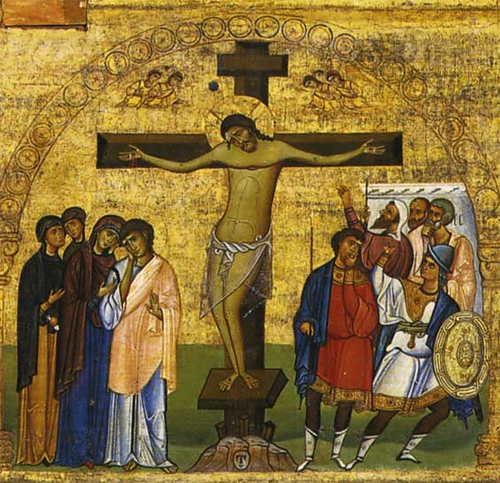

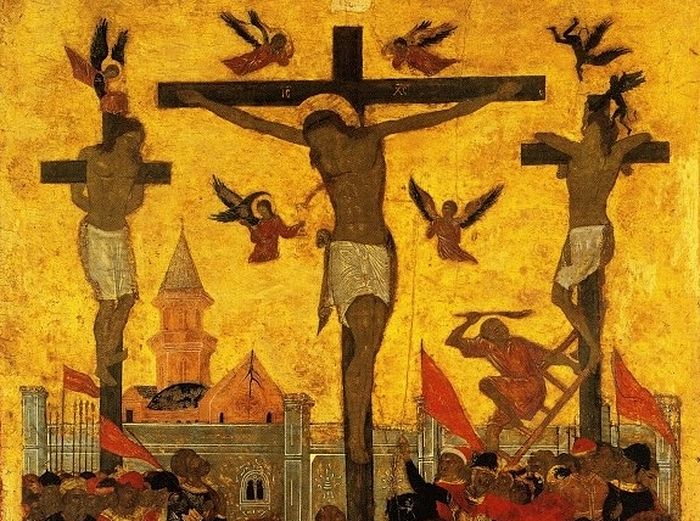

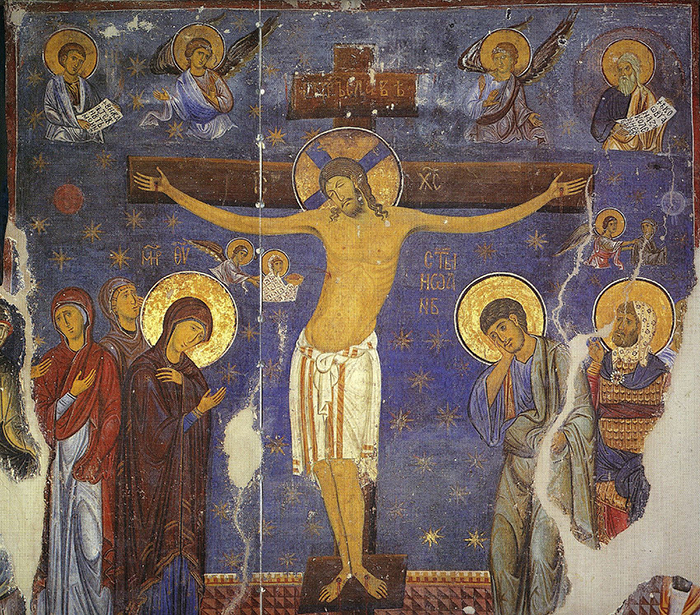

The usual iconographic depiction of the Crucifixion includes both Gospel accounts and poetic images from worship hymns and theological interpretations of the holy fathers.

Not just a man dies, but God Himself, and this is an event of universal proportions.

Today the One Who hanged the earth on waters hangs on the tree; the King of Angels wears a crown of thorns…

Both the chant and the icon already anticipate the Resurrection.

The established Orthodox iconography (see our short article A Few Words about the Image of the Cross on the iconography of the Cross and Crucifixion) depicts Christ not at the moment of death, not in agony on the cross, but as already dead. The position of His arms indicates the unconditionally open embrace of the whole world with His love.

Some icons depict Christ with open eyes, others with closed eyes – both ways are perfectly canonical. In the first case, His divine nature is emphasized, while in the other case He is portrayed as a human being.

The loincloth and the naked human body of Christ are a symbol of his vulnerability and surrender to human hands.

The cave with Adam’s skull is traditionally depicted under the cross. According to a legend, Adam the First Man had been buried on Golgotha. The Holy Fathers who reflected upon the events of the Gospel often saw it as something special: Adam threw mankind into the kingdom of death by his disobedience; Christ, the “new Adam”, by being obedient to the Father, overcame death and tore mankind out of its power.

Some icons depict crying angels.

Some icons and frescoes show an interesting and quite common scene: to the left of the Lord is a depiction of the Old Testament Church, and to the right is the New Testament Church. One of them, represented by the image of an angel, is approaching Jesus, and the other is being driven away by another angel. Frescoes and icons often show the New Testament Church with a Chalice in her hands, in which She collects the Blood that flows from the Savior’s wound as a symbol of the Communion that Christ offers to all who believe in Him “for the remission of sins.”

![]()

The theme of the Mother of God standing at the cross is special, as it shows how intense the pain of the pierced mother’s heart was. The presence of John the Theologian at the Cross signifies the faithfulness of the disciple who, unlike others, did not leave the Teacher at His worst hour.

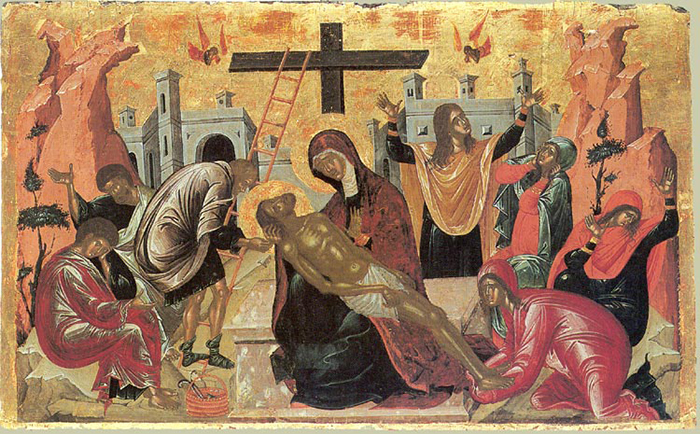

The images of such scenes as Deposition from the Cross, Lamentation, Laying in the Tomb deserve special attention.

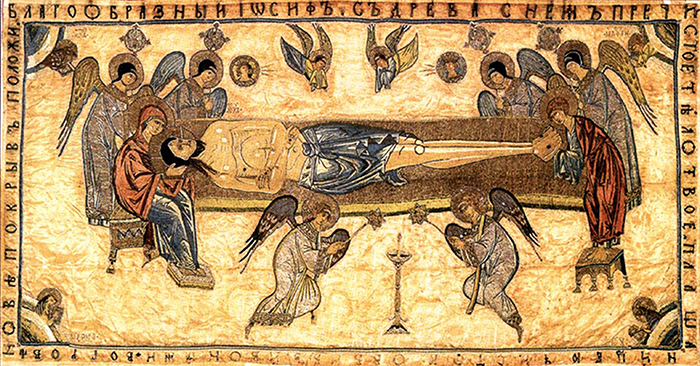

Traditionally, the iconographic image is emotionally restrained, but the Lamentation and Laying in the Tomb are exceptions to this rule. The emotions in the Lamentation icon in a church in Nerezi (North Macedonia, 12th century) are very vivid. The face of the Virgin Mary, who clings to the face of the dead Christ, as well as the faces of his disciples and angels, are marked by grief and deep sorrow.

A similar scene appeared at the same time in the paintings of the Mirozhsky Monastery in Pskov, but the face of the Virgin is more reserved.

The theme of Christ’s death received a particularly deep interpretation in Eastern Christian iconography in the icon called Weep Not For Me, O Mother, which discloses the relationship between the Mother of God and Her Divine Son. We find this image in both ancient and new iconography.

The icon Tenderness has the same compositional scheme, where the Mother of God also presses Christ the Child to her bosom. This interconnection of images adds the theme of anticipated Passion to the iconography of Tenderness, and the theme of love to Weep Not For Me, O Mother. It is love that conquers death.

Surely, we cannot get around the theme of the burial of Jesus Christ. For the most part, it is represented not by icons but by embroidered or painted Shrouds featuring the image of the dead Christ, which are placed in the middle of the church in lieu of the analogion icon.

Ancient icons emphasized white (clean) burial shrouds of Christ, as a symbol of both birth and death. It is no coincidence that burial shrouds resemble baby swaddling clothes: they clearly echo the icons of the Nativity of Christ, where Baby Jesus rests in swaddles in the Bethlehem cave.

All these allusions are supposed to underscore the human nature of Jesus, His birth and death, and everything that He voluntarily accepted for the redemption of men.

The burial is followed by the Holy Saturday, the day of peace, light and silence, the secret Easter, filled with anticipation of the explosive triumph of the Resurrection of Christ.