The second installment of the talk on iconography with Father Sergious, the head of the icon-painting studio and icon painting school at St. Elisabeth Convent:

The iconography of the Mother of God is thoroughly developed in comparison with other types of icons. There are twelve major feasts in the liturgical year of the Orthodox Church. Some of these feasts are related to the life of the Mother of God. There are icons of such feasts, too. There is not much information about the Mother of God in the Holy Scriptures. We do not have detailed descriptions of her appearance, either.

There is a description of what Jesus looked like, which is allegedly a later compilation because it could not possibly appear in the 1st century, in spite of what it claims; and there is a description of what the Mother of God looked like, too. This description not only states that she was good-looking but also provides a lot of details concerning the color of her

There is a description of what Jesus looked like, which is allegedly a later compilation because it could not possibly appear in the 1st century, in spite of what it claims; and there is a description of what the Mother of God looked like, too. This description not only states that she was good-looking but also provides a lot of details concerning the color of herhair, her eyes, and her height. I believe that this description is likely an invention of a pious author who lived much later. This could happen because before the invention of the printing press, the texts of the Holy Scriptures circulated in manuscripts.

Nicephorus Callistus, a Church historian, cited the following iconographic convention with regard to the appearance of the Mother of God: Her height was average, or, as some say, slightly above average; she had golden hair; her eyes were sparkling and somewhat olive in color; her eyebrows were arched and black-ish; her nose was oblong; her lips were luscious and filled with sweet words; her face was neither round, nor narrow, but slightly long; her hands and fingers were long, too.

Interestingly enough, even the texts written by such authors as Plato or Socrates – i.e., the heritage of the antiquity – survived to the present day in such manuscripts. These manuscripts were copied by Christians, I must add. Though why would they need the heritage of pagan antiquity, it may seem? In any case, all texts were distributed by copying, and each scribe had the temptation to enrich the text somehow or add something to it in the process. Maybe this is the reason why such later insertions, that claimed to be authentic, crept into the original texts.

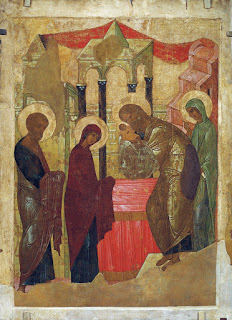

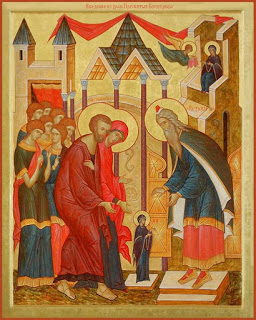

Icon of the Entry of the Mother of God into the Temple

This is an iconographic depiction of one of the twelve major Orthodox feasts. It is interesting to observe how a certain event in the life of a saint – the Mother of God in this case – later becomes not just a story, not just a description of something that happened at a certain time: it acquires eternal meaning thanks to the icon. See, the remarkable composition that the icon painter found, was not by mere chance.

Joachim and Anne, the parents, point at the little Virgin Mary. The High Priest meets her in the Temple, and there is a column that grows from within her and supports the canopy over the altar. Its color is similar to the light with which her omophorion shines. She, the Mother of God, is like that column on which, basically, the living temple rests. The icon teaches us dogmatic truths through these images, although these are not evident sometimes. Here we have an interesting interpretation of the event because, naturally, such Royal Doors could not exist in the Jerusalem Temple.

All these notions: The Holy of Holies, the Temple, the Mother of God – they gradually become tightly intertwined in church hymns and worship books. The Mother of God enters the Temple; at the same time, she also becomes, in essence, the Temple of God, she becomes the Holy of Holies because it is she who gives birth to Christ, it is through her that God incarnates in a way that’s impossible for a human reason to grasp. The symbol of this Holy of Holies, the Old Testament Temple – it really becomes prophetic, so even the Tabernacle and all Old Testament images are understood in the light of the New Testament.

I would like to note that in terms of iconography, the Mother of God always has the same age, in fact. Even in her childhood (e.g., she is said to be 3 years old by the time of her entry into the Temple). If we look at the Mother of God as portrayed on this icon, it would be hard for us to deduce her age from the proportions of her body. You can’t say that here she is, for example, a toddler, and then she grows older and older, and when she stands by the Cross, she is even older. By the time of the Annunciation, she was younger than 18; by the time of the Savior’s death, she was around 50 already. She was even older by the time of her Dormition (Assumption).

The Mother of God looks the same on all icons, and this is what makes the language of iconography so special: it is so symbolic that the question of age does not arise. On the contrary, when icons pretend to be realistic, there immediately appear some strange inconsistencies: we see the Savior on the Cross, and a young Mother of God stands beside him. So when they become so much like us (I mean, when icons are painted in the realistic manner), there is that strange situation: something must be wrong – they do not look like a Mother and a Son. However, the icon manages to avoid this awkwardness.

Born in Antiquity

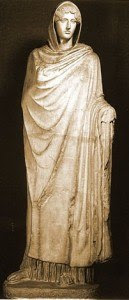

The clothes of the Mother of God and her appearance – and the way people painted her on the icons – have their roots in antiquity. See this statue from an Istanbul museum that boasts a very good collection of Christian and antique art. You see, this kind of clothes was typical of women in the Middle East – a

The clothes of the Mother of God and her appearance – and the way people painted her on the icons – have their roots in antiquity. See this statue from an Istanbul museum that boasts a very good collection of Christian and antique art. You see, this kind of clothes was typical of women in the Middle East – atunic resembling a long dress, and an omophorion – a veil that covers not only one’s hair but almost her entire body. A traditional outfit of an Oriental woman became a norm for the iconography of not just the Mother of God but also almost all women we see on icons, with an exception of several special cases. A woman’s hair was covered, as a rule, to signify that she was married. We never see the Mother of God with uncovered hair or with flowing hair on canonical icons, unlike in the Western art, which freely exploits this image.

There hardly were images of the Mother of God on early icons, miniatures, and frescoes, that we could immediately recognize. (Mosaic) This is an icon of the Mother of God, and you might not even be able to guess that it is an icon of the Annunciation. See how strange it looks for us. There are many Angels, one of which soars above the Mother of God’s head like a dove, while she sits on her throne doing handcrafts. There is an Angel standing beside her, who announces the Good News to her. The Mother of God wears the clothes of a rich and noble Roman woman, with decorations, even earrings. It is strange for a God-fearing modern person to see the Mother of God wearing earrings. It is quite evident that the traditions that we deem sacrosanct, are in fact relative and have a historical development of their own. It wasn’t so shocking for ancient people to portray the Mother of God in such a way; it was nothing out of the ordinary.

The Diversity of Iconographic Faces

The countless diversity of the icons of the Mother of God may be divided into several groups. First of all, it is Panachranta, or The Immaculate.

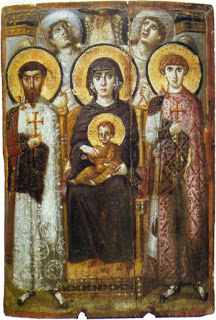

For instance, this is one of the earliest icon types that shows us the Mother of God sitting on the throne. It is an antique tradition again, but the Mother of God wears the traditional garments – a tunic and an omophorion. She is easily recognizable here. The Mother of God is portrayed together with martyrs, and there are two Angels standing behind the throne, like guards who protect the Most Holy Virgin. This icon was painted using encaustics, like almost all early icons. Such an icon is painted on a wooden board using hot wax paints. The famous Faiyum mummy portraits were also made using such a technique.

In general, this technique makes it difficult to paint tiny details, but ancient icon painters were really good at it: take note of the fact that the face of the Mother of God on this icon is lifelike. Strangely for us, it does not look ascetic: she has big eyes and fresh complexion. Despite some asymmetrical traits, her face is filled with inner vigor.

This mosaic has a similar composition: the Mother of God sits on the throne. Her fingers make a fairly rare gesture: we seldom see women on icons making this hand gesture. As a rule, this gesture is typical of the Savior, the Apostles, sometimes Angels, but female saints and the Mother of God are almost never portrayed with their hands making this gesture. This is, perhaps, the only such case. She wears regular clothes, apart from the cap that covers her hair. Her omophorion is cherry red, and she has gold stripes on her tunic.

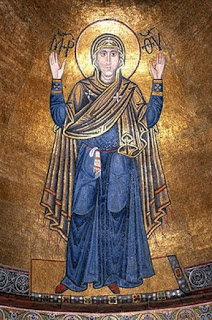

A similar icon is located in the conch of the Hosios Loukas church in Greece. The Mother of God is shown with the attributes that we are accustomed to – the three stars on her omophorion that symbolize her perpetual virginity. That is, she was a virgin before the Nativity, a virgin during the Nativity, and a virgin after the Nativity of our Savior. The inscriptions “Mother” on the left and “of God” on the right accompany this image. Generally speaking, the conch is the focal point of the entire church, so to say. It is in the conch, in the center of the artistic ensemble, that the icon of the

Mother of God sitting on the throne with Baby Jesus on her lap is located.

Mother of God sitting on the throne with Baby Jesus on her lap is located.

The Reigning icon of the Mother of God is another example of this type of icons. The globus cruciger, sceptre, and crown are a later tradition: these regalia had not been displayed on icons in the ancient times; it must have come to us from the West even. The Catholics have a tradition: when an icon becomes highly venerated and exceedingly important, they “crown” that icon. The Pope issues an edict, and they put a crown onto that widely-acclaimed icon. Gradually, after having been copied or reprinted several times, this crown would become an inalienable attribute of the image itself. Though, of course, the Mother of God does not need these royal insignia. Nevertheless, they are present even in the Orthodox iconography; but we must be aware of the fact that they are a later addition.

The Reigning icon of the Mother of God is another example of this type of icons. The globus cruciger, sceptre, and crown are a later tradition: these regalia had not been displayed on icons in the ancient times; it must have come to us from the West even. The Catholics have a tradition: when an icon becomes highly venerated and exceedingly important, they “crown” that icon. The Pope issues an edict, and they put a crown onto that widely-acclaimed icon. Gradually, after having been copied or reprinted several times, this crown would become an inalienable attribute of the image itself. Though, of course, the Mother of God does not need these royal insignia. Nevertheless, they are present even in the Orthodox iconography; but we must be aware of the fact that they are a later addition.

We have to mention that when the Mother of God is depicted sitting on the throne, this does not mean that she did sit on a throne: in fact, she never sat on any throne during her life. Nonetheless, this image has become a standard since the

earliest times, and it has been repeated through various epochs, in different

ways, and in different styles.

earliest times, and it has been repeated through various epochs, in different

ways, and in different styles.

Another iconographic type is called Hodegetria, or “Showing the Way.” It is a very widespread icon type. The most famous examples of the Hodegetria type are: Our Lady of Smolensk, Iveron icon of the Mother of God, Tikhvin icon of the Mother of God, icons of the Mother of God of Georgia, the Mother of God of Jerusalem, the Mother of God of Three Hands, Mother of God of Passion, the Black Madonna of Częstochowa, Mother of God of Cyprus, Mother of God of Abalak, the Surety of Sinners icon of the Mother of God, etc. The Mother of God is portrayed pointing at Christ. Jesus saith unto him, I am the way, the truth, and the life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me. (John 14:6)

Her hand points at the Way. Usually, the Savior is portrayed almost full frontal, as well as the Mother of God. Her face is amazingly meek on this icon painted by Dionysius. When you look at her, you cannot understand how the artist managed to achieve it, and it is staggering. As an icon painter, I would love to find out how he made it but I realize that everything is built around so many nuances here, it is so refined, that you almost find it impossible to imagine how a person could paint this with his hands. At the same time, it seems that this image is very simple, and there is nothing special about it. However, this image is so amazing that you can delve into it deeper and deeper, you can look into this depth that is deeper than Mona Lisa. In fact, Mona Lisa is very majestic, too. It is a profound portrait in a sense. You can explore it, too, but this icon is much deeper and has to be approached in a different way.

The icon of the Mother of God of Kazan belongs to the same type. It may be called a “shoulder-length Hodegetria” – we don’t see the hands of the Mother of God here. We see the Savior who looks straight at us and extends his hand in blessing.

Tenderness (Greek Eleousa, έλεουσα)

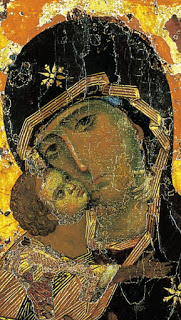

Some of the icons that belong to this type are among our most favorite and well-known, such as the Our Lady of Vladimir icon, which is now located in Tretyakov Gallery, in a special chapel and an icon case that protects this icon against adverse atmospheric conditions. Anyway, one can venerate this icon and pray in front of it. This icon is unique because only the faces of the Mother of God and the Savior were painted by its original author, whereas the rest of the icon was painted later. This icon was painted in the course of several centuries. The faces were painted in the twelfth century, and some of the other elements were painted in the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. A person who see this icon for the first time may think that this is how it should be. In fact, the color of vestments, the hands, and the gold hatching on the baby used to be completely different. Radically different. If we saw this icon as it had been intended to be, we might not even recognize it. We’ve got used to this image, so naturally, when a contemporary icon painter paints it like this, he makes a mistake from

the point of view of historical accuracy, because this situation developed with time. Some people write about this icon that it was Holy Evangelist Luke who painted this icon using a board that had served as the tabletop during the Last Supper. But that’s impossible, I mean the painting style: St. Luke could not paint this icon because the way it is painted is attributed to the twelfth century. It is possible that Holy Evangelist Luke painted the Mother of God but it is difficult to say how he did it and in what manner. Possibly, the icons that he painted have survived to the present day in later copies. It is only in this sense that one can say that Our Lady of Vladimir was painted by St. Luke, but not in the literal sense that people sometimes put into it.

the point of view of historical accuracy, because this situation developed with time. Some people write about this icon that it was Holy Evangelist Luke who painted this icon using a board that had served as the tabletop during the Last Supper. But that’s impossible, I mean the painting style: St. Luke could not paint this icon because the way it is painted is attributed to the twelfth century. It is possible that Holy Evangelist Luke painted the Mother of God but it is difficult to say how he did it and in what manner. Possibly, the icons that he painted have survived to the present day in later copies. It is only in this sense that one can say that Our Lady of Vladimir was painted by St. Luke, but not in the literal sense that people sometimes put into it.This icon is painted in the Byzantine style. After it was brought to Russia, it was involved in many historic events. We have several feasts dedicated to this Vladimir icon of the Mother of God. It was thanks to prayers in front of this icon that our Russian Orthodox civilization was rescued several times. So it is natural that the icon of the Mother of God of Vladimir is something like a spiritual magnet that attracts people. Whenever I visited Tretyakov Gallery, I always saw people approach this icon with immense awe and faith.

What is special about this iconographic type? The fact that the faces of the Mother of God and the Savior are so close to one another, which is why one of the names for this icon is A Tender Kiss. Their faces are so close to one another because they love one another as a mother and a son. It is through this unity that the love of God towards man is expressed. The Mother of God represents the entire humankind, and the Savior represents God. God is so close to us; He saves us without alienating us. He is really engaged with the human beings. This image is so wonderful. The Vladimir icon has many replicas. These replicas aren’t “copies” in the contemporary meaning of this word in ancient times. When someone ordered a replica of an icon of the Mother of God, the icon painter made this icon according to the style and the way of looking at things that was typical of his time and his school.

The icon of the Mother of God of the Don also belongs to the same type. It is located in Tretyakov Gallery, too. According to some experts, it was Theophan the Greek who painted the Don icon. The icon of the Mother of God of Zhirovichi belongs to the same type, too.

Yet another iconographic type is called Hagiosortissa, or Prayerful. There were no such elaborate iconostases in churches in ancient times, so people would often paint an image of the praying Mother of God on a left pillar or column, and an icon of the Savior on the right pillar. This icon type shows the Mother of God without Baby Jesus: she raises her hands in prayer, and she has a scroll in her hands with a prayer to the Savior. Take, for example, this icon. It has a very complex composition: the elders of Solovki kneel in supplication to the Most Holy Mother of God, and she, in turn, prays to the Savior.

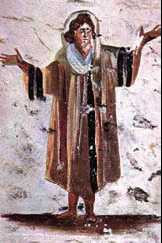

One of the other most prominent types of iconography is Oranta. See these hands raised in prayer? This hand gesture had already existed in ancient Jewish worship. You might recall a scene from the Old Testament when the elect people fought their enemies, and the Lord told Moses that as long as you stand with your arms raised up (it is a symbol, of course), the Israelites will win. Moses stood and prayed, and the Israelites were winning that battle. However, if you try keeping your arms up, you will know how hard it is. Moses’ arms gradually moved down – and immediately, Israelites began losing their battle, so in the end, some people would stand beside Moses and support his arms.

One of the other most prominent types of iconography is Oranta. See these hands raised in prayer? This hand gesture had already existed in ancient Jewish worship. You might recall a scene from the Old Testament when the elect people fought their enemies, and the Lord told Moses that as long as you stand with your arms raised up (it is a symbol, of course), the Israelites will win. Moses stood and prayed, and the Israelites were winning that battle. However, if you try keeping your arms up, you will know how hard it is. Moses’ arms gradually moved down – and immediately, Israelites began losing their battle, so in the end, some people would stand beside Moses and support his arms.

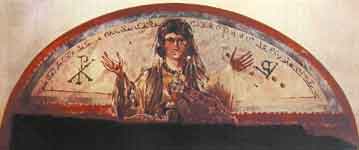

Thisgesture of one’s arms raised in prayer existed in the Old Testament practice: you see, it made its way into the art of catacombs, too. Later it became a way of displaying prayer. You may have noticed our priests in the sanctuary raise their hands at certain times during the worship.

Here we see a fairly ancient icon from the catacombs: the Mother of God with her hands up, and Christ shown in her womb. Here is a well-known mosaic in Kyiv. It is remarkable how this church managed to survive all wars: it dates back to the twelfth century, and it was constructed even earlier. The mosaic dates back approximately to the 12th century. So there is the icon of Oranta, also known as the Indestructible Wall or the Sign, in the apse of this church. People call this type of image differently sometimes.

An Orthodox church is designed in such a way that all images are interconnected: the Mother of God in the conch prays to the Savior in the dome. Why do they call this kind of icons “The Sign”? It is because the Savior shown in the womb of the Mother of God is not yet born, it is something like a sign that the Divine Child will be born of a Virgin. She does not hold him in her arms. Sometimes the Savior on ancient icons is portrayed in such a way as if he has not yet appeared. There is even an ancient icon where the Divine Baby is almost invisible on the vestments of the Mother of God.

All Creation Rejoices in Thee…

Some icons depict very complex narratives, such as “All Creation Rejoices in Thee.” In fact, this is the name of a hymn to the Most Holy Theotokos sung during the Liturgy of St Basil the Great, which is celebrated on Sundays of the Great Lent. Basically, this Liturgy is celebrated only ten times a year. This wonderful hymn “All Creation Rejoices in Thee, O Virgin Full of Grace…” is sung at the moment when a priest in the sanctuary reads the profound and powerful prayers of St Basil the Great for everyone who loves or hates us: all creation, including all Angels, all people, all the earth.

The author of this late 16th century icon is Dionysius who tried to translate hymns into iconography. Everything is still very traditional here. St John Damascene, the author of this hymn, is shown on this icon with a scroll in his hand. He is the closest figure to the Mother of God, as if he is the one who sings this hymn to her. Here we see Angels, Apostles, High Priests, bishops, holy monks,

hermits, prophets, holy women, right-believing princes and princesses. The Mother of God is shown with a big halo around her, which is called a “mandorla”. All these people are focused on prayer to Jesus Christ and His Mother. If you listen to this hymn and look at the icon, you’ll be surprised how the painter managed to match the poetic symbolism of the hymn with his icon. A rare image and a remarkably great composition.

hermits, prophets, holy women, right-believing princes and princesses. The Mother of God is shown with a big halo around her, which is called a “mandorla”. All these people are focused on prayer to Jesus Christ and His Mother. If you listen to this hymn and look at the icon, you’ll be surprised how the painter managed to match the poetic symbolism of the hymn with his icon. A rare image and a remarkably great composition.

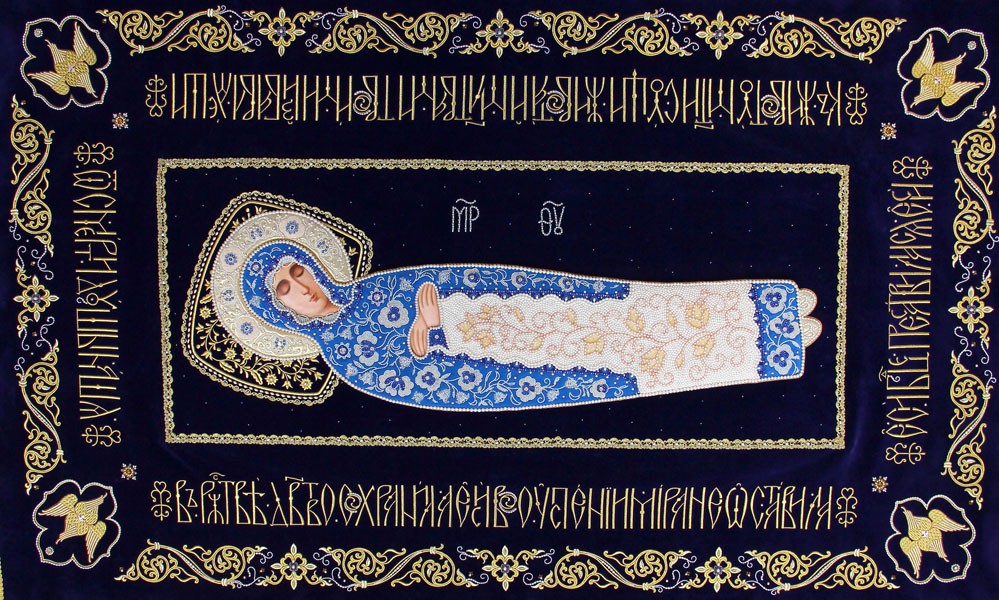

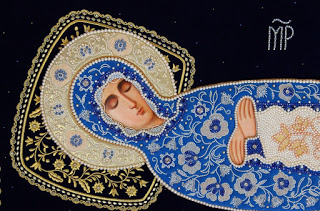

Holy Shroud

There is a holy shroud of the Lord Jesus Christ with an image of the Savior in the tomb in every Orthodox church. A similar holy shroud, but with an image of the Mother of God, is in many churches and monasteries. It symbolizes the Theotokos at the moment of her death – the Assumption, and is almost universally used in worship. Such a Shroud entered the church usage under the influence of Jerusalem tradition in the 19th century. There is a Shroud of the Most Holy Mother of God in a small church at the Gethsemane metochion, which became the prototype and the pattern for later copies. Nowadays, a shroud is a carved flat wooden figure of the Mother of God laid on a blue velvet base decorated with gold embroidery. The face and the hands of the Mother of God are painted; her vestments are decorated with precious and semiprecious stones and pearls.

All Creation Rejoices in Thee…