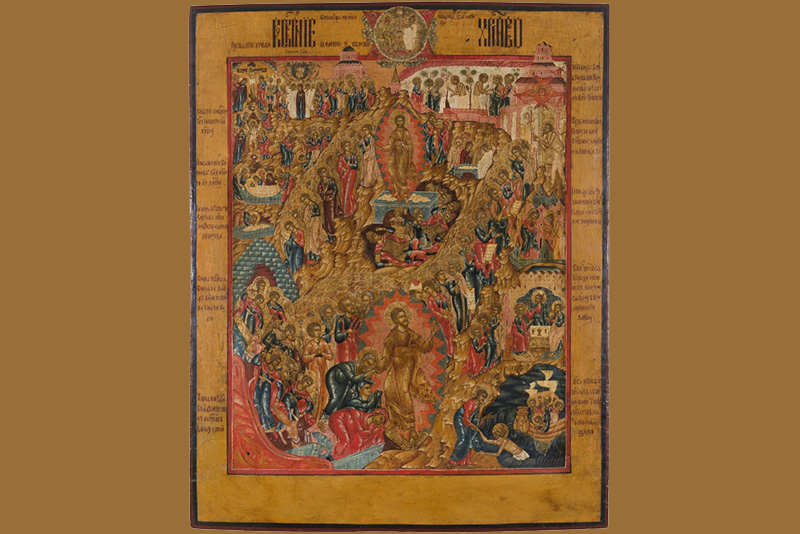

We have seen Resurrection icons here previously, but today we will look at a rather remarkable example, extraordinary in its detail and the number of related scenes included. It is Russian, from the 19th century.

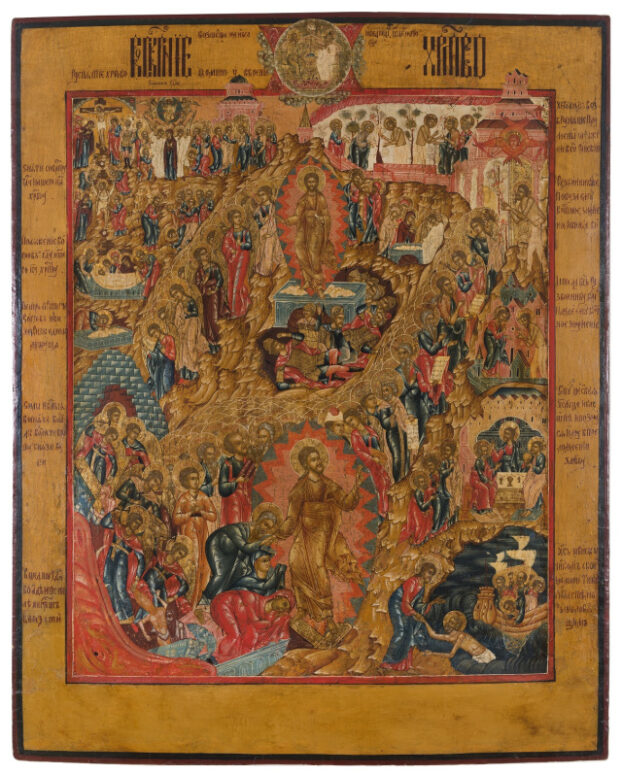

At the top we see a heavily abbreviated title inscription. Here is the left side of it:

It reads in large vyaz lettering:

ВоСКР[ЕСЕ]НIЕ

VOSKRESENIE

“RESURRECTION”

Notice how cleverly the left vertical of the K as been shortened at top and bottom to fit within the arms of the C (“S”).

It finishes at top right:

ХР[ИС]Т[О]ВО

KHRISTOVO

“[of] CHRIST”

That strange letter in the middle is the T, with the left vertical shortened to fit below the top of the P (“R”), and the right side extended into a long vertical. Remember that in some icon inscriptions, T looks very much like an English “M.” That is the case here, though it has the left vertical shortened.

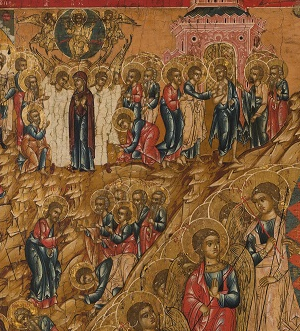

Now you will recall (I hope) that early icons of the Resurrection depicted it as the descent of Jesus to Hades, where he releases the righteous men and women of the Old Testament from their imprisonment . Later Russian icons, however, often add to that the “Western” image of the Resurrection — Jesus rising above his empty tomb. And that is what we see in the center of this example. At top is the “Western” Resurrection, and at bottom the earlier “Descent to Hades” form:

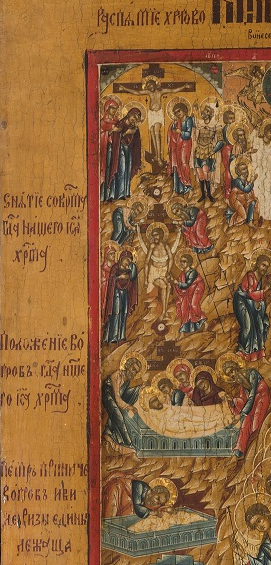

Taken as a whole, however, the icon is meant to tell the Resurrection story from the Crucifixion to the Ascension of Jesus. It begins top left with the Crucifixion:

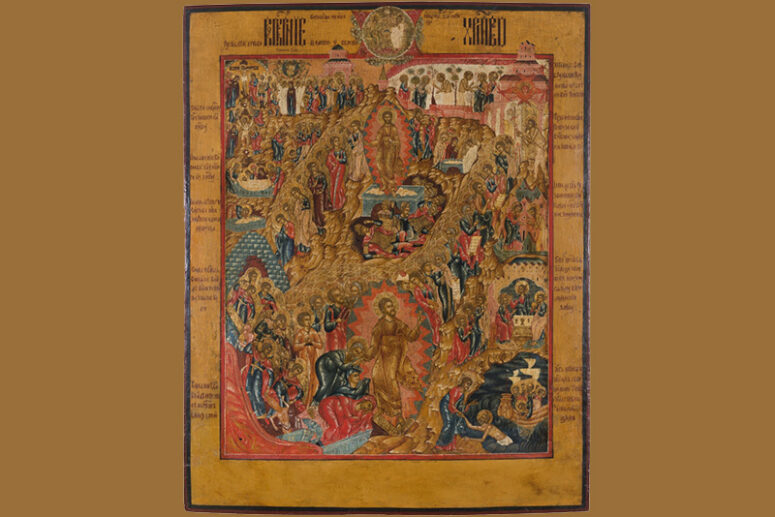

The smaller inscriptions identify each scene. At top is the Raspyatie Khristovo — the “Crucifixion of Christ.” Below that is the Snyatie so Kresta — the “Removal from the Cross.” Then comes the Polozhenie vo Grob — the “Placing in the Tomb.” And at the base we see that Peter has come to the tomb, and sees the linen graveclothes lying there.

Then we have to jump to the right of Jesus in the upper “Western” Resurrection, where the painter has squeezed in two more small scenes — at right the “Myrrh-bearing Women” listening to an angel at the tomb, and at left the appearance of Jesus to Mary Magdalene (as previously mentioned, this is an amalgamation of discrepant Gospel accounts of the Resurrection).

At lower left, we see the angels who have been commanded to subdue Hades, along with various devils, and the mouth of Hades depicted as the open jaws of a frightful beast — another borrowing from Western European art.

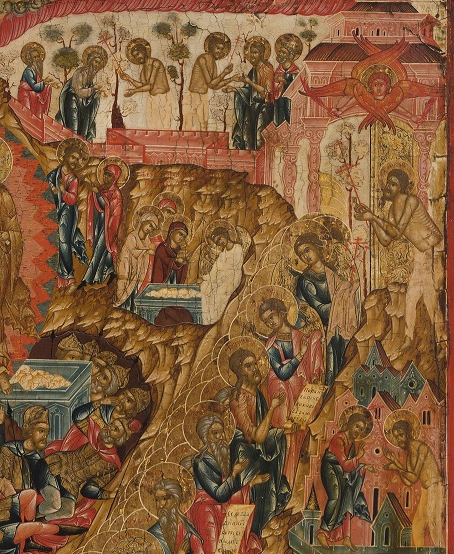

In the “Descent to Hades” form of the Resurrection, we see Jesus freeing the righteous men and women of the Old Testament, including Adam and Eve:

At right we see the long line of freed prisoners rising up to the Gates of Paradise, notable among them the “Repentant Thief” who is called Rakh in Russian icons. He is the fellow in white pants, holding a cross. In the lower part of this segment we see Jesus giving Rakh the cross that will be his “ticket” into Paradise:

So we see Rakh with Jesus and his cross, and above that at the Gates of Paradise, and then he is inside the Garden of Paradise with other saints and Old Testament worthies. Note the Seraph with flaming swords who guards the gates.

Now if we look at the “Western” Resurrection, we see Jesus rising above the tomb (note the sarcophagus with the empty graveclothes). Below him is a group of astonished Roman guards (found only in the Gospel called “of Matthew”), fallen to the ground.

At lower right we see two post-Resurrection scenes. At top is Jesus meeting two disciples on the road to Emmaus, and beside that the scene of their recognizing him while sitting at table, when he breaks the bread.

Below that is the scene of the resurrected Jesus meeting the disciples (that is Peter coming out of the water) at the Sea of Tiberias.

Finally, we have to jump back to the upper left side to see the small scenes of Jesus being touched by Thomas at right, Thomas bowing before him at lower left (with the other disciples), and the end of the whole tale at upper left, where the disciples and Mary, standing with angels, see Jesus ascending to heaven — the Voznesenie — the “Ascension.”

An icon such as this is, as I often say, a kind of graphic novel in paint. A believer could move his or her eyes about the icon to follow the story, noting each incident and its participants.

As I have mentioned before, the iconography of the Resurrection is a conglomeration of elements from various sources, both biblical and extra-biblical. And even using those sources found only within the Bible requires glossing over their incompatible discrepancies to make an attempt at a unified story. But keep in mind that Russians — until quite recent times — were not Bible readers. Most people were illiterate. At the end of the 18th century, only somewhere between 1 and 12% of peasant males could read. Around a quarter of city dwellers were literate. Nobles had the highest literacy rates at about 84-87%, and about 75% of merchants were literate. By 1897, about a quarter of the population of the western part of Russia was literate, with the highest rates still among the wealthy, the nobles, merchants, and clergy, and peasants far below them. Bibles were not easy to obtain or affordable, though the New Testament was more often to be found than the Old. Most people learned the Bible stories through the readings in the liturgy and through the images on icons, so there was much less chance of noticing all the “holes” in the sewn-together account as seen in icons such as this one.

The spread of the New Testament in Russia was largely made possible by the efforts of Protestants, via at first the British and Foreign Bible Society — which led to a Russian Bible Society. Even when New Testaments began to appear at affordable prices, they were often in Church Slavic, and finding a Bible also containing the Old Testament often proved difficult even into the 20th century. The reading of the Bible in Russian rather than Church Slavic is a comparatively recent phenomenon.

In spite of all these difficulties, we nonetheless find that in the 19th century religious classic often known in English as The Way of a Pilgrim, the Pilgrim — poor as he was — mentions owning a Bible:

Я по милости Божией человек-христианин, по делам великий грешник, по званию бесприютный странник, самого низкого сословия, скитающийся с места на место. Имение мое следующее: за плечами сумка сухарей, да под пазухой Священная Библия; вот и все.

“I am by the grace of God a Christian man, by my deeds a great sinner, by calling a homeless wanderer of the humblest birth, roaming from place to place. My belongings are the following: on my back a knapsack of dried bread, and in my breast pocket the Holy Bible — and that is all.”

Source: A VERY DETAILED RESURRECTION ICON – ICONS AND THEIR INTERPRETATION (wordpress.com)