Klobuk (Turk kalpak – hat) is the everyday headdress of monastics and bishops, also used for celebrating certain divine services. Klobuk’s equivalents in the Greek Churches, are the kamelaukion ( καμελαύκιον), perikephalaia (περικεφαλαίαν), or less commonly, the small koukoulion (μικρὸν κουκούλιον). The history and the origin of the klobuk remain largely unknown. We can neither say exactly when it appeared, nor when/how it became a monastic headdress. Although the history of the klobuk can be traced to no earlier than the beginning of the second millennium, it appeared much earlier than that.

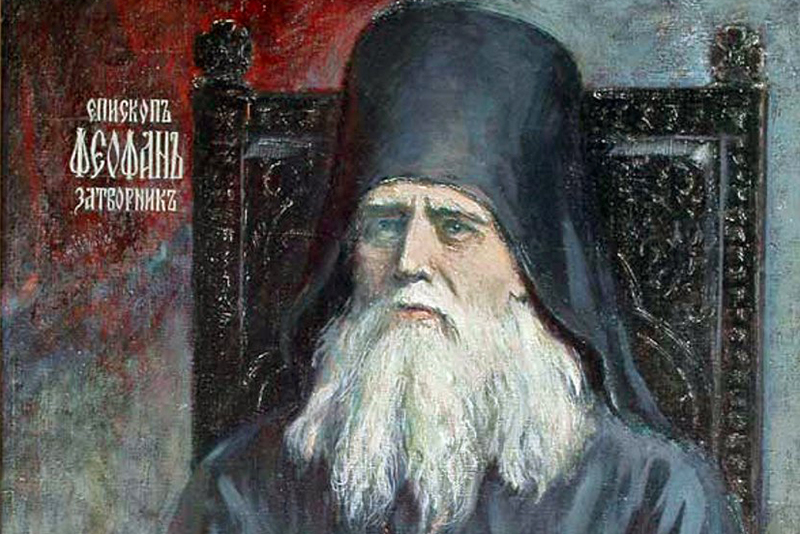

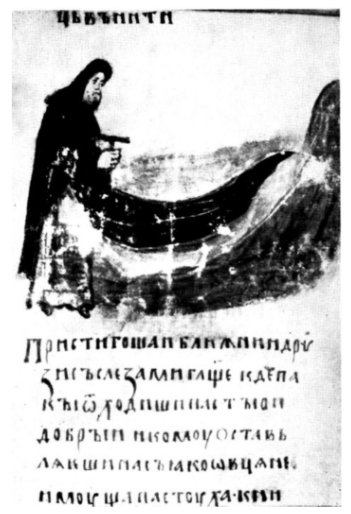

The earliest known images of the klobuk are found in the Slavic translation of the Hamartolos’ chronicle, dating back to the 14th century. The klobuk is depicted there as a headdress with veils, descending onto the chest and back. Notably, the klobuk in this miniature is worn by St Athanasius of Alexandria, who lived in the 4th century. Similar depictions of the klobuk are found in the miniature images of the Theological Works by John VI Kantakouzenos (late 14th century).

The Louvre Museum collection contains a headdress of the 4th-7th centuries, which may be the prototype of the modern klobuk. It is a small hat with miniature flaps, covering the ears, and an image of the cross on the forehead. It is not known exactly what kind of headdress this was.

In the 8th-13th centuries, with the division into the Lesser and Great Schemas, schema-monks began wearing koukoulia, while the headdress worn in the Little Schema was called the kamelaukion or the small koukoulion. It is quite possible that the hat kept in the Louvre could be one of those.

It is also very likely that the spread of monasticism to northern areas introduced the need for a new headdress. Combining the ancient koukoulion with a veil, resulted in the appearance of a practical item, appropriate to the climate.

A similar headdress can be seen in a mural image of St Euphrosynos in Macedonia, dating from the end of the 12th century.

In Russia, in the 12th-13th centuries the word klobuk was used for a princely headdress, in which the part adjacent to the head was covered with fur. In some cases a prince’s klobuk could be modified with a small veil falling onto the shoulders. Such klobuks can be seen on icons of the Saints Boris and Gleb.

Originally, a monastic klobuk consisted of a kamelaukion covered with a veil. Kamelaukia, traditionally made from camel hair, acquired their name from Greek κάμηλος – camel and served as protection from the sun. In Russia kamelaukia were replaced by small knitted hats. This version of a klobuk was called a captyr.

The klobuk appears in the Russian rite of monastic tonsure after the 15th century, whereas the inner and outer kamelaukia (kalimafi and epikalimafi) are mentioned in the Byzantine rubrics of the 13th century.

The veil of a kamelaukion was also called a maphorion (from Greek ωμοζ – shoulder and φέρω – “I wear”). Modern veils are made of thin fabric, whereas in ancient times the fabric was dense, to serve as protection from the weather.

It is not known exactly when the veil of a kamelaukion became divided into three parts. According to a later theological interpretation, this was done for the sake of glorifying the Holy Trinity. Another possible explanation is the ancient tradition of tying the ends of the veils in cold and windy weather like a scarf under the chin. During the divine services, the split veil is used to tie the klobuk at certain parts of the divine service, when it is necessary to remove the headdress, freeing the hands of its owner.

After the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans, the klobuk takes on a slightly different look. All men were required to wear headdresses of a certain type and colour. The colour of the headdress was determined by the social category. A sultan or a vizier wore white headdresses, janissaries and civil servants wore red, common Muslims wore green, and everyone else wore black.

Ordinary Muslims and other commoners were obliged to wear fezzes, headdresses similar to the Byzantine kamelaukion. This changed the appearance of the kamelaukion, in fact turning into a fezze.

Besides, monks were not allowed to wear veils on kamelaukia outside the walls of their monasteries, since veils were also a distinctive feature of the Ottoman nobility. This has become so deeply ingrained in the Byzantine tradition that even now, the veil remains removable and is not worn by Greek monastics outside monasteries, churches and services. NB, hierodeacons serve without the veil, most likely due to purely practical considerations. The veils of the Russian klobuks are sewn to the headdress and cannot be removed.

Greek nuns wear neither kamelaukia nor klobuks, since fezzes were worn by men only. In the Russian Church women are allowed to wear klobuks, for in Christ “there is no longer male or female” (Gal. 3: 28).

The new type of klobuk penetrated into the Russian Church under Patriarch Nikon (1652-1666), who became the first to wear a Greek klobuk, soon introducing Greek-style vestments in the Russian Church by one of the provisions of his church reform.

The old-style klobuk is now used only by the Old Believers, and by the primates of the Russian and Georgian Orthodox Churches. In the Russian Church, the old-style klobuk was restored together with the restoration of the patriarchate so that the patriarch could be distinguished from other bishops.

The symbolic meaning of the klobuk is revealed in the rite of monastic tonsure. Putting the klobuk over the head of the new monastic, the person performing the tonsure says, “Our brother, so-and-so, accepts the helmet and guileless hope of salvation, so that he may stand against all the wiles of the devil, being clothed with the veil of humility and obedience, as a sign of spiritual wisdom, securing and cherishing the ruling part of his intellect unshaken from adverse assaults, in the name Father and Son and Holy Spirit”.