Many will be aware of the role of catacombs in the early history of the Christian Church. Yet the nature of this role was as straightforward as it seems.

The use of the catacombs had a long tradition in Christianity and also in Judaism and Paganism. Catacombs never served as a dwelling, but mostly as a burial site. Nor were they common in all locations. Christians built them only in places where the geological conditions were conducive. One example of a well-known catacomb is the caves of Rome; similar structures existed in Sicily, Malta, Egypt, Tunisia, Gallia, Palestine and elsewhere.

Catacombs shaped the evolution of Christian burial rites, the order of the liturgy, the veneration of the saints and the icon painting tradition of the Church.

The practice of catacomb digging was grounded in the Christian teachings on human nature and salvation. Christians view the human body as a wondrous creation of the Lord and part and parcel of human nature, which is fundamentally good. They also acknowledge the temporary demise of the body, until the time when it will come back to life as we meet our Saviour at His Second Coming. In light of these teachings, the spread of Christianity displaced the practice of cremation, Creating the demand for burial sites.

Initially, the people buried in the catacombs were of different faiths – Christian, Pagan, Jewish, or Mithraism, among others. Eventually, the Christian communities began to purchase land parcels exclusively for Christian burials. At the turn of the second century of our time, Christian burial sites had nothing in common with the present-day cemeteries. The largest and best-known are the catacombs of Callixtus and Saint Januarius in Naples.

The Catacomb of Saint Callixtus (named in honour of the Bishop of Rome who reigned from 217 to 222), was the first example of a tunnel-type catacomb in history. It was built near the famous Via Appia near Rome. Christians built galleries along the perimeter connected them with passages and created several layers of niches for burials.

As noted, catacomb building was not a practice common exclusively among Christians; however, there were almost no Pagan or Jewish catacombs left by the third century. Where mixed burials were still practised, the ratio of Christian to Pagans epitaphs was 600 or more to one.

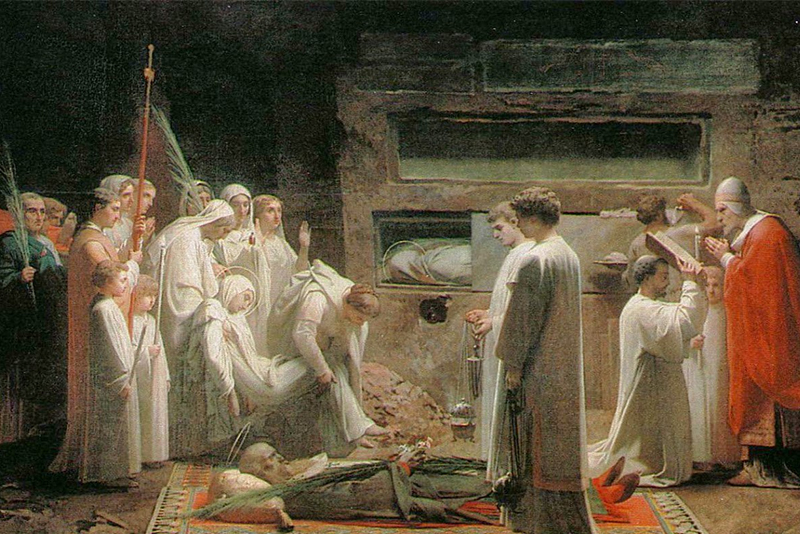

The Edict of Milan (313) accelerated the establishment of the practice of the veneration of the saints. Pope Damasus prohibited the building of any structures above the catacombs. In response, Christians began to be designate underground spaces as worship areas at or near the graves of the Christian martyrs. Simultaneously, extensions of the catacombs began. Stairs and dome arcs were added, and wells were drilled to let in fresh air and sunlight. Multiple epitaphs were replaced with longer texts with descriptions of the lives of the holy martyrs, some of them rhymed.

As a result of these developments, some catacombs along the suburban roads of Rome grew to five kilometres in length and stood out among the features of the suburban landscapes. Situated among multiple country houses and villas, they became places of great public significance. In ancient times, burials within the city limits were prohibited in most cities throughout the empire. Because Alexandria was one of the few exceptions to this rule, its catacombs were dug in the urban territory.

The ordinances did not begin to change until the middle of the sixth century when the urban populations dropped, and the demand for burial grounds subsided. Simultaneously, rising military insecurity also put pressure on lawmakers to allow burials in cities. Yet these changes did not change the attitude to the catacombs as sacred places among early Christians. They continued to build Christian churches in their vicinity, as large numbers of the Christian faithful were flocking to venerate the saints.

A century later, travelogues (also called itineraria) began to appear, with directions to particular graves or underground churches. Concurrently, church artists begin to decorate with frescoes the walls of the underground spaces. Contemporary art scholars date the last of these frescoes to the turn of the ninth century.

Towards the end of the first millennium, the practice of building catacombs went into decline. Already in the 7th and 8th centuries, the faithful begin to move the relics of their saints from the caves inside the built churches. Over thirty carts with the relics were taken out of the catacombs during the reign of Pope Bonifacius IV, and 2300 relics of the Christian martyrs were placed in overground churches under Pope Paschalius I. In the middle ages, the flow of visitors to the catacombs dwindled and almost disappeared towards the 14th century. As a result, many catacombs became neglected. The rise of Christian archaeology in the 15th and 16th centuries revived the interest in the catacombs.

As underlined above, building catacombs was not an exclusively Christian practice. The origin of the catacombs was linked to the subterranean structures called hypogea – serving as necropolises – that spread the Mediterranean long before the Nativity of Christ.

The architecture of the catacombs depended on the type of the subsurface rock. For example, Rome stands on volcanic tuff, a type of easily malleable igneous rock. Some catacombs were extended by adding tunnels to the hypogea or subsurface quarries. Most were built from scratch, in hills or flat rocks.

There was rarely an outline or a plan, and new spaces were added in an ad-hoc manner. Some catacombs were extended by building tunnels, others by building more niches and reinforcing the floor. The most respected members of the community were buried in separate polygonal rooms called cubicles, or, more rarely, in stone sarcophagi.

The position of a catacomb digger was highly professional and well respected. Catacomb diggers, or fossors, oversaw the building of subsurface corridors and spaces and were also responsible for the distribution of the graves and the organisation of funerals.

* * *

The above narrative leads us to the conclusion that early Christians did not use catacombs as hideouts or dwellings, but only as spaces for joint worship, prayers and burials. The notion of a catacomb church is a 20th-century invention. At present, it is used by fanatical schismatics who build underground cellars and call on their misguided followers to go into hiding from the world, abandoning their jobs, families and communities. None of these renegade practices has anything to do with the authentic Christian life or the catacombs of the early Church.

Translated by The Catalogue of Good Deeds

Source: https://spzh.news/ru/istorija-i-kulytrua/84209-katakomby–podzemnaja-zhizny-khristian-vchera-i-segodnya

In famous older novels like “Quo Vadis” the early christians are shown as praying and hiding inside the catacombs with their “Ponitfex Maximus” Apostle Peter. Even some pagan Romans went secretly there to her the new preachings of God.

“An old hypogeum between the Viæ Salaria and Nomentana. That pontifex maximus of the Christians, of whom I spoke to thee, and whom they expected somewhat later, has come, and to-night he will teach and baptize in that cemetery. They hide their religion, for, though there are no edicts to prohibit it as yet, the people hate them, so they must be careful…

Chilo bent toward Vinicius and whispered,—“This is he! The foremost disciple of Christ-a fisherman!”

The old man raised his hand, and with the sign of the cross blessed those present, who fell on their knees simultaneously. Vinicius and his attendants, not wishing to betray themselves, followed the example of others. The young man could not seize his impressions immediately, for it seemed to him that the form which he saw there before him was both simple and uncommon, and, what was more, the uncommonness flowed just from the simplicity. The old man had no mitre on his head, no garland of oak-leaves on his temples, no palm in his hand, no golden tablet on his breast, he wore no white robe embroidered with stars; in a word, he bore no insignia of the kind worn by priests—Oriental, Egyptian, or Greek—or by Roman flamens. And Vinicius was struck by that same difference again which he felt when listening to the Christian hymns; for that “fisherman,” too, seemed to him, not like some high priest skilled in ceremonial, but as it were a witness, simple, aged, and immensely venerable, who had journeyed from afar to relate a truth which he had seen, which he had touched, which he believed as he believed in existence, and he had come to love this truth precisely because he believed it. There was in his face, therefore, such a power of convincing as truth itself has. And Vinicius, who had been a sceptic, who did not wish to yield to the charm of the old man, yielded, however, to a certain feverish curiosity to know what would flow from the lips of that companion of the mysterious “Christus,” and what that teaching was of which Lygia and Pomponia Græcina were followers.

Meanwhile Peter began to speak, and he spoke from the beginning like a father instructing his children and teaching them how to live. He enjoined on them to renounce excess and luxury, to love poverty, purity of life, and truth, to endure wrongs and persecutions patiently, to obey the government and those placed above them, to guard against treason, deceit, and calumny; finally, to give an example in their own society to each other, and even to pagans.

Vinicius, for whom good was only that which could bring back to him Lygia, and evil everything which stood as a barrier between them, was touched and angered by certain of those counsels. It seemed to him that by enjoining purity and a struggle with desires the old man dared, not only to condemn his love, but to rouse Lygia against him and confirm her in opposition. He understood that if she were in the assembly listening to those words, and if she took them to heart, she must think of him as an enemy of that teaching and an outcast.

Anger seized him at this thought. “What have I heard that is new?” thought he. “Is this the new religion? Every one knows this, every one has heard it. The Cynics enjoined poverty and a restriction of necessities; Socrates enjoined virtue as an old thing and a good one; the first Stoic one meets, even such a one as Seneca, who has five hundred tables of lemon-wood, praises moderation, enjoins truth, patience in adversity, endurance in misfortune,—and all that is like stale, mouse-eaten grain; but people do not wish to eat it because it smells of age.”

And besides anger, he had a feeling of disappointment, for he expected the discovery of unknown, magic secrets of some kind, and thought that at least he would hear a rhetor astonishing by his eloquence; meanwhile he heard only words which were immensely simple, devoid of every ornament. He was astonished only by the mute attention with which the crowd listened.

But the old man spoke on to those people sunk in listening,—told them to be kind, poor, peaceful, just, and pure; not that they might have peace during life, but that they might live eternally with Christ after death, in such joy and such glory, in such health and delight, as no one on earth had attained at any time. And here Vinicius, though predisposed unfavorably, could not but notice that still there was a difference between the teaching of the old man and that of the Cynics, Stoics, and other philosophers; for they enjoin good and virtue as reasonable, and the only thing practical in life, while he promised immortality, and that not some kind of hapless immortality beneath the earth, in wretchedness, emptiness, and want, but a magnificent life, equal to that of the gods almost. He spoke meanwhile of it as of a thing perfectly certain; hence, in view of such a faith, virtue acquired a value simply measureless, and the misfortunes of this life became incomparably trivial. To suffer temporally for inexhaustible happiness is a thing absolutely different from suffering because such is the order of nature. But the old man said further that virtue and truth should be loved for themselves, since the highest eternal good and the virtue existing before ages is God; whoso therefore loves them loves God, and by that same becomes a cherished child of His.

Vinicius did not understand this well, but he knew previously, from words spoken by Pomponia Græcina to Petronius, that, according to the belief of Christians, God was one and almighty; when, therefore, he heard now again that He is all good and all just, he thought involuntarily that, in presence of such a demiurge, Jupiter, Saturn, Apollo, Juno, Vesta, and Venus would seem like some vain and noisy rabble, in which all were interfering at once, and each on his or her own account. But the greatest astonishment seized him when the old man declared that God was universal love also; hence he who loves man fulfils God’s supreme command. But it is not enough to love men of one’s own nation, for the God-man shed his blood for all, and found among pagans such elect of his as Cornelius the Centurion; it is not enough either to love those who do good to us, for Christ forgave the Jews who delivered him to death, and the Roman soldiers who nailed him to the cross, we should not only forgive but love those who injure us, and return them good for evil; it is not enough to love the good, we must love the wicked also, since by love alone is it possible to expel from them evil…”