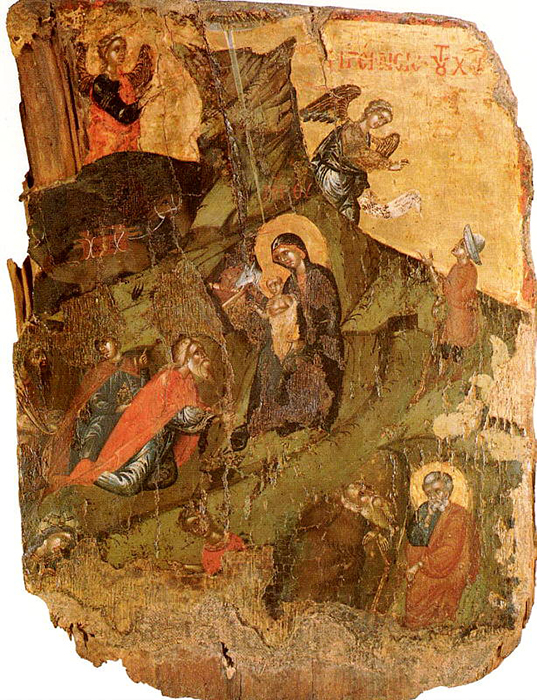

The beautiful tradition of putting up a nativity scene on Christmas exists in many homes. Nativity scenes are models of the Bethlehem cave, and the events in it. One can buy them ready-made in a shop or at a market. Some make them with their own hands. In Europe, the tradition has continued uninterrupted for many centuries.

Nativity scenes were also popular in pre-revolutionary Russia. After the revolution, Christmas-related traditions became the prime target of intense anti-clerical agitation, and the tradition of making nativity scenes stopped. Much of it was forgotten for many years.

In the 1980s, the tradition started to return. Ideological pressure had weakened, and the students of folklore grasped at the opportunity to explore openly the traditions of popular and religious arts. Nativity scenes occur in different forms and shapes. The domestic versions come with the figures of the Infant Christ, the Mother of God, Joseph, angels, shepherds and animals. They are made with fur tree branches which are put on top and make it look like a mini-tabernacle. The custom is to hang the installation above the festive icon of the Nativity so everyone who comes to venerate can visualise what the nativity cave might have looked like from within. In some of Russia’s coldest regions, such as Yakutia, visitors may encounter nativity scenes made from ice.

The Russian word for the Nativity scene, vertep, is translated as ‘cave’ or ‘grotto’. It refers to the cave in Bethlehem which was the birthplace of Christ.

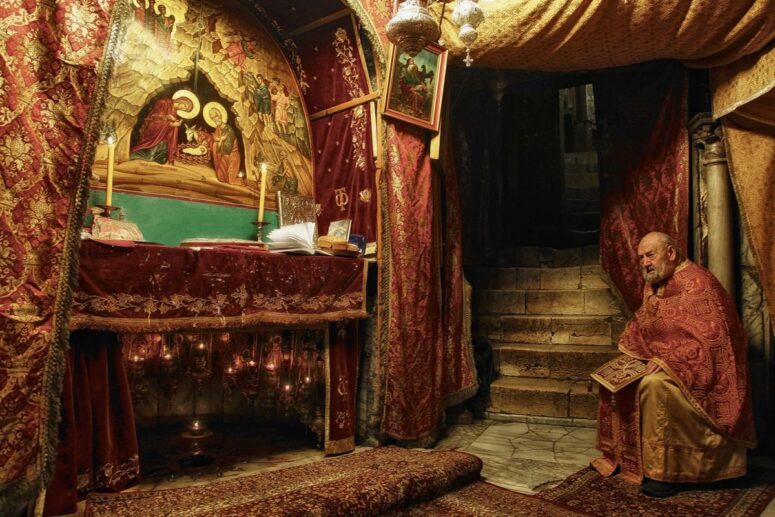

The Nativity Grotto is found under the altar of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. The exact spot where Christ was born is marked with a silver star and an inscription under it in Latin: “Here Jesus Christ was born to the Virgin Mary.” Sixteen lights stand in the semicircular space above the star. A short distance away from the lights is the Grotto of the Manger, the traditional site where Mary laid the newborn baby. The manger which Mary used as the cradle for the newborn was taken to Rome in the 7th century and is kept there as a great relic. The niche of the manger has been laid with marble.

Christ’s birthplace, the cave, was the model for the nativity scenes that artisans have been creating for centuries.

Over time, nativity scenes have been made of different materials – carved wood, cardboard, paper-mache, clay, porcelain, gypsum and much else. Sophisticated and simple, big and small, the nativity scenes were a prized resource for educating the illiterate about the Bible. Saint Francis of Assisi is credited with creating the first live nativity scene in 1223 on the Holy night in Greccio, in order to cultivate the worship of Christ. He called his reconstruction the manger scene, or presepe, in Italian. This tradition spread far beyond Italy to many other parts of Europe and the world. They recreate the scenes with Baby Christ, the Mother of God, Joseph, the angels and the shepherds and let the viewer experience them in the streets of their home towns. There are whole streets on some of Europe’s cities – such as Naples, Italy – with large numbers of nativity scene workshops concentrated in a small space.

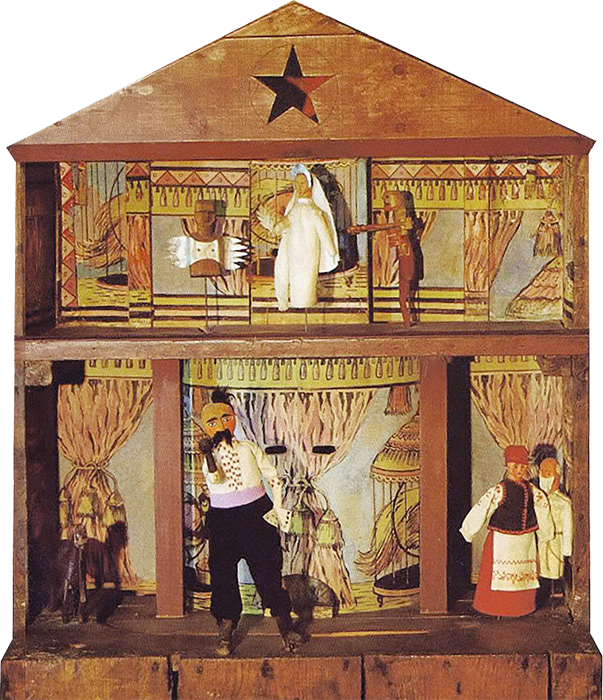

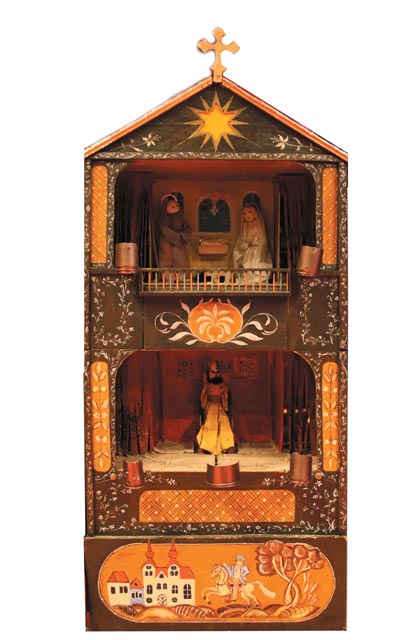

In Russia, presepes were also common. Far more popular, however, were the theatrical versions of the nativity scene, the portable Christmas puppet theatre presenting the events of the Nativity. They typically represented wooden boxes, two or three stories. They were used to re-enact for the public the Christmas mystery drama consisting of the episodes from the Gospel. The Christmas drama was shown in secular homes and the homes of the priests. Dynasties of Christmas drama showmen began to appear by the late 18th century, of whom the Kolosov family were an outstanding example. Their performances exemplified the established tradition of Christmas puppet shows for more than a century.

The art of Christmas puppet drama reached its high point in the 19th century, spreading beyond Central Russia to Siberia. Portable Christmas puppet shows roamed the streets and villages of Russia through the beginning of the 20th century. The performances were becoming progressively secular, and as biblical mysteries were being given less and less prominence than popular comedies. The show typically consisted of two parts – the Christmas mystery and a musical comedy with local variations. By the end of the 19th centuries, the audiences had become more interested in the comedy scenes in the lower story than in those played out in the upper stories of the box. Simultaneously, the show season became progressively longer, extending beyond the Twelvetide period up until the end of the Pancake Week. Reportedly, Christmas puppet shows were on at the Nizny Novgorod fair, which opened as late as 15 July.

The anti-clerical campaign that followed the October Revolution of 1917 ended the practice of Christmas puppet shows. Just like the other attributes of Christmas – including the traditional Christmas tree – they were prohibited. The traditional scripts and performance techniques were forgotten. In 1980, the folklore ensemble of Dmitry Pokrovsky launched a project to revive the lost tradition. In it, he was helped by Victor Novatsky, a known historian of the puppet theatre and a theatrical director. He explored the practices of Christmas puppet theatre from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, and inspected the theatre boxes at the Bakhrushin Museum and the Sergey Obraztsov theatre. After a long and detailed study of the old tradition, he recovered but by bit its elements and attributes, the scripts and the ways to bring life to the puppets. His work provided a model for modern successors.

How does the portable Christmas theatre work?

To begin with, let us look at the construction of the theatre box from within. Inside the beautifully decorated box, we find slots in which the puppets move. The puppets cannot move from one level to another. The top storey is used for playing scenes from the life of the Holy Family, and the bottom one to depict the palace of King Herod. In later times, it was also used for satire and comedies. However, the Christmas theatre box is more than an enclosed space; it is a model of the world – the top storey represents the heaven, the lower storey the earth, and the pit into which Kind Herod falls, the underworld.

During wintertime, the portable Christmas theatre was transported on horse-drawn sledges from house to house, and village inns. Benches were put in front of the box, lights came on, and the show began.

The traditional cast of the performance were the Mother of God, Joseph, the Angel, the Shepherd, three Magi, Herod, Rachel, the Soldier, the Satan, Death and the Sexton. The latter was charged with lighting the candles on the box at the start of the performance. Each puppet was attached to a pole so the handler can move it along the slots in the floor by the lower end of the pole.

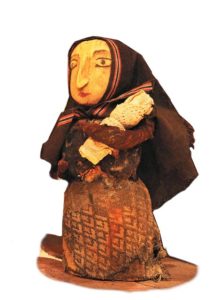

Simple everyday objects were used to depict the characters in the scene; a roll of white rope represented the baby Christ, and a ball of yarn the sheep accompanying the shepherd who had come to venerate Him. Most puppets were of wood or cheap fabric. They were easy to make and easy to transport.

The owners of potable theatre boxes were also bound by one unwritten rule: the puppet of the Mother of God must be distinct from all the other puppets as if a professional artist had made it. The same rule applied to the puppet of the Saviour and was strictly followed. Sometimes, the Icon of the Theotokos was used instead of the puppet.

So what was the typical script?

It was based on the story of the advent of Christ. The angel announces the coming of the Saviour. A shepherd and three Magi come to venerate the newborn Christ. The Magi recount their meeting with King Herod to whom they foretold the birth of the would-be Great King. The angel tells the Magi not to go to King Herod and not to let him get hold of Christ, as Herod is afraid that the newborn King would take away his power. Enraged, King Herod tells the warrior to kill all infants in Bethlehem. Rachel comes and implores King Herod to spare her son. In Rama was there a voice heard, Rachel, weeping for her children, and would not be comforted, because they are not (Jeremiah 31:15), Matthew 02:18). Herod is unmoved. The Angel comforts Rachel. Death comes to Herod, he asks her for a reprieve, but she calls in the Devil, who drags him away into hell.

After the second part of the show, consisting mainly of short comedies, the puppets take leave from their audience.

Boris Goldovsky, a student of the Christmas mobile theatre tradition, says that each show is accompanied by music, which is at least as important as the performance itself. The music enriched the description of the characters and strengthened the sensation of the feast. Popular chants were the most common, representing a combination of musical folklore and popular dance music.

The portable Christmas puppet theatre remains a cherished tradition in the celebration of Christmas. Along with the other types of nativity scenes – static, mechanical, or even live, they are an indispensable element of the celebration, which takes the viewer to the place in Bethlehem whether the new covenant with God began.

Did you know…

The antecedents of the nativity scene tradition date back to ancient times. Ancient Greeks had a similar tradition of making puppet theatre performances on a board placed on top of a column. The decorations in the show changed when the curtains were drawn in front of the column.

A two-storeyed theatre box similar to the portable Christmas puppet theatre was described in the first century by Heron of Alexandria, a mechanic. It had mechanical puppets that were put in motion by a lever. The top storey was for Gods and the bottom one for the Argonauts.

Scholar Boris Goldovsky writes that the first theatrical performances dedicated to Christmas took place during the reign of Pope Sixtus III in the fifth century. The Pope believed, wisely, that the best way to reach the hearts of the illiterate people was to act out the scenes from the bible before them. At approximately the same time, still Nativity Scenes began to be put up in churches, depicting the Baby Christ in the manger and the animals bending over Him.

Some Russian scholars believe that nativity scenes have been around in Russia since its Christianisation, and the first nativity scenes were panoramic. However, material evidence of the use of nativity scenes dates back to the last decades of the 16th century. The oldest Christmas theatre found in the Russian empire was made in 1591, as indicated on its label.

Victor Novatsky discovered some simple secrets of the trade related to Christmas puppet theatres. For example, how can the Magi in the play kneel before the Baby Christ, despite having no movable parts in them? The secret is in the length of the workpiece from which the figure of the Magus was made: it is significantly shorter than its clothing. Or, how does the head of the figure of King Herod come off, when Death cuts it off with its scythe? Answer: the figure was not made as a whole piece. Its head was affixed to the pole by which it was moved. The handlers pulled on the pole, and the head came off.

Translated by The Catalogue of Good Deeds

Source: https://foma.ru/tradiczii-i-istoriya-rozhdestvenskogo-vertepa.html