In the year 633, the pagan King Penda of Mercia invaded the kingdom of Northumbria in northern England, which had become Christian a short time before. In the same year the saintly king Edwin of Northumbria was killed and the three surviving princes of Northumbria had to move to Scotland, settling on the great monastic island of Iona, where Celtic monasticism flourished at that time. Some time passed.

One of these princes returned to his native Northumbria but was killed by the pagans. The next prince to return to his native land was St. Oswald who was filled with religious zeal and intended to make his country Christian again. In 634 St. Oswald defeated the pagan army headed by Penda at Heavenfield near Hadrian’s Wall and thus freed Northumbria from the occupiers. At that time there was only a handful of Christian missionaries there, such as the holy Deacon James of York. But there was no resident bishop. Aware of the lack of brilliant preachers, Oswald sent for a missionary to Iona. The first missionary who came from Iona was Corman, but he was very stern with the Angles and could not speak their language, so he soon had to go back. On his return to Iona, Corman told the brethren: “What a hopeless task it is to preach to these savage and stubborn Angles!” One of the monks, named Aidan, answered him gently: “Brother, you were probably too strict with these illiterate people.” So it was decided to send Aidan to Northumbria.

St. Oswald came to love Aidan and gave him the island of Lindisfarne (another name: Holy Island) situated off the north-eastern shores of England in the present-day county of Northumberland. St. Aidan was thus destined to become the apostle of Northumbria and one of the most venerated English saints, while Lindisfarne for many years was to become one of the greatest centers of monastic and ascetic life in the whole of Britain.

St. Aidan was born in Ireland in the late sixth century, probably in the province of Connacht. Nothing is known about his early years, though he must have been one of the spiritual children of St. Columba of Iona, the enlightener of Scotland and founder of the famous monastery of Iona. Aidan became a monk on this island and was trained in the Irish tradition. He led a strict ascetic life and became famous as a holy and virtuous man. As we said, in about 635 at the request of King Oswald St Aidan, with some of his brethren, left for Northumbria to enlighten northern England and become the bishop of the Northumbrians who had been converted to Orthodoxy before the pagan invasion.

In the same year Aidan was consecrated bishop; he made Lindisfarne the center of his see and the main base of his missionary labors, building on this island a church and establishing a monastery. Thus the new Diocese of Lindisfarne was formed; Aidan ruled it as a bishop from Lindisfarne and simultaneously was abbot of the newly-founded monastery. The new diocese stretched from the River Forth in Scotland to the River Humber in northern England. Lindisfarne resembled Iona; its location was near the palace of the kings of Northumbria in Bamburgh and was an ideal place as the center of the new mission. It was from here that the evangelization of the North of England began.

Aidan, the first Celtic missionary in the land of the Angles (hence the name “England”), travelled the length and breadth of Northumbria. In the first years of his labors Aidan and his monks were often accompanied by King Oswald—as an interpreter—because it took some time for Aidan to master the language the Northumbrians spoke. Most of the information on the life of St. Aidan and his achievements in enlightening the north Angles is known from the work by the Venerable Bede, the Church History of the English People. St. Bede wrote about St. Aidan with a love and cordiality that he used for no other saint apart from St. Cuthbert. In Northumbria Aidan constructed a large number of churches, monasteries and schools, ransomed many Anglian boys from slavery and instructed them in Church teaching. He inspired the newly-baptized people to keep all the Church fasts and to understand the Holy Scriptures. Aidan himself lived in extreme poverty and abstinence, and at the same time he frequently denounced the rich and the strong of this world for their wastefulness and their oppression of the poor.

Everybody loved Aidan for his patience and kindness. Walking from one village to another, the holy man spoke in a simple language with local inhabitants, telling them about Christ and gradually arousing interest in Christianity in their hearts. He was patient and gentle with them, showed a sincere interest in their everyday life and labors, trying to support and console them, and the Northumbrians easily understood his simple speech and opened their hearts to him. Thus, after some period of time, Aidan and the monks who accompanied him on his journeys, gradually, settlement after settlement, led the whole of Northumbria to know Christ. Later Aidan took twelve youths from among the Angles to study in the Lindisfarne monastery as he wanted the future bishops and teachers of faith in Northumbria to be from among local people.

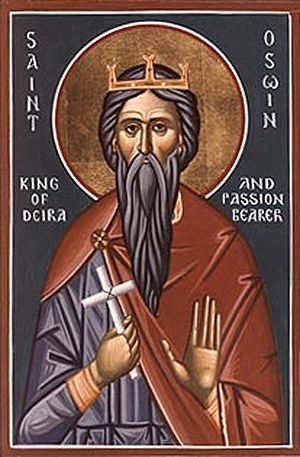

The holy King Oswald, who was of the same spirit as St. Aidan, did his best to support him. Once when Oswald gave alms very generously to the poor, Aidan praised him for his mercy and predicted that his right arm would remain incorrupt (and this prophecy was fulfilled). Unfortunately, in 642 King Oswald was slain in battle with the heathen, headed by Penda. After the martyrdom of St. Oswald, Northumbria was for some time split into two provinces: Deira and Bernicia.

The holy King Oswin became ruler of Deira in south Northumbria (the present-day Yorkshire). He illustriously ruled his country for seven years and gained the general love of the people of Deira. According to the Venerable Bede, St. Oswin was “a man of outstanding humility and piety”. The king was tall and handsome, very amiable and generous to everyone: to common people and the wealthy alike. Oswin was filled with love for Aidan as well, in every possible way supported his mission and (like Oswald before him) was an interpreter for the hierarch. Aidan regarded Oswin as his dear friend. But Oswin was not very happy with the extreme voluntary poverty of Aidan who quickly gave out all the gifts he received to the needy. Once St. Oswin gave Aidan a horse so that he would not continue to go on foot during his long missionary journeys. But Aidan in his humility refused the royal present and immediately gave the horse to a poor peasant who needed it for ploughing.

This is what Venerable Bede wrote on St. Aidan some eighty years after his repose: “The best commendation of his (Aidan’s) doctrine was the fact that he together with his followers taught no otherwise than they lived. For he never thought about or cared for any amenities or comforts of this world, but at once handed over the gifts he received from kings and noble men to the first pauper that he encountered. Everywhere—in town or village—he travelled on foot and never on horseback. In all things his course of life was so different from the slothfulness of our time… Neither respect nor fear prevented him from exposing the sins and vices of the rich of this world whom he sharply rebuked. Whatever gifts of money he received, he either distributed them to the use of the poor or bestowed them on ransoming those who had been wrongfully sold for slaves. He afterwards made many of those he had ransomed his disciples, and after having taught and instructed them, advanced them to the order of the priesthood.”

During the Lenten fast Aidan used to retire to Inner Farne—a small isle in the North Sea near Lindisfarne (belonging to the Farne Islands), where, imitating other Celtic ascetics and anchorites, he remained for long contemplative prayer, seeing before him nothing but the sea and the birds. In 651, staying on this isle, Aidan saw that the pagan Mercians, led by King Penda, attacked Bamburgh and set its walls on fire. The ascetic instantly offered up fervent prayer to God—and behold, the wind miraculously changed and the fire started moving towards the pagans. Through the prayers of Aidan the town was rescued, and the pagans ran away. That is why St. Aidan is venerated by some as the patron-saint of firemen.

One day St. Aidan, sitting at table in King Oswin’s court, suddenly started weeping bitterly. When a priest who was sitting nearby asked him what had happened, Aidan replied that it had been revealed to him that King Oswin was not to live long because his people were unworthy of such a pious and God-fearing ruler as he was. Aidan’s prophecy soon became true. In the same year Oswiu, King of Bernicia—the northern part of Northumbria, seized by lust for power, murdered King Oswin.

Aidan outlived his faithful friend only by eleven days: he reposed in the Lord on August 31 (September 13 new style), 651. The ministry of St. Aidan as bishop and missionary in Northumbria lasted for 16 years. He passed away inside the church of the royal residence in the vicinity of Bamburgh (the capital of Northumbria), and before his death the ascetic fell ill. At night when the holy apostle of Northumbria reposed, one very young man who was tending sheep high in the Scottish mountains saw the soul of Aidan being carried in great glory by angels to Heaven and eternal bliss in the dwellings of Paradise. The next morning this youth learned about the saint’s repose. This miracle inspired the young man to seek monastic life. This young shepherd was the future St. Cuthbert, who was to become the greatest English saint. That is why these two saints are sometimes depicted on icons together, though they did not know each other personally.

The life of St. Aidan was full of wonderful miracles. He was himself a visionary and wrought numerous amazing miracles, some of which were related by St. Bede. Once a certain priest was entrusted with a task: he was to travel to Kent to Princess Enflaed in order to take her from there by sea to Northumbria, where she would marry King Oswiu. This priest came to St. Aidan and asked him to pray for him while he was on the journey. The saint gave him some blessed oil and said that during the voyage they would meet a terrible storm on the way back, but if he would pour out oil onto the sea, the ship would be saved. It all happened according to the words of Aidan: as they were sailing to Northumbria, the vessel was caught in a severe storm, and all the passengers could have perished at any moment. But the priest remembered the command of Aidan: he poured out the blessed oil into the sea and it became calm without delay.

Here is another famous miracle which occurred at the intercession of St. Aidan after his repose. As we said, the saint died in Bamburgh. In the last minute of his life Aidan leaned against the external wooden prop of the local church. Afterwards that church was burned down by pagans but the prop was absolutely undamaged. Later the church was rebuilt, but because of the neglect of the local inhabitants it burned down once more. The same prop remained intact this time again. Then the church was reconstructed anew and the prop was placed inside the new building. From that time on many people were healed on that site and their petitions were fulfilled.

Countless miracles occurred at the relics of St. Aidan after his repose. First he was buried in a grave on Lindisfarne and soon afterward his relics were translated to the main monastery church of Lindisfarne. In the 660s a portion of his relics was translated by St. Colman of Lindisfarne to his native Ireland. In 793, Vikings plundered the monastery on Lindisfarne, which is why a portion of St. Aidan’s relics in the early ninth century was translated far to the southeast: to the famous Glastonbury monastery. From that time veneration of St. Aidan (who was widely venerated throughout northern England and Scotland) extended to Mercia or central England. It is quite possible that his relics were also kept on Iona in Scotland. In a word, the veneration of the holy hierarch became national. As for Lindisfarne, the raids of Norwegians and Danes on England and Scotland in the ninth century became frequent and nearly permanent, so that monastic life on the Holy Island stopped until the eleventh century, when a Catholic priory was founded there in about 1093. This monastery existed till the Reformation and was dissolved in the 1530s. Now only ruins survive of the monastery.

Tireless in his preaching of the Gospel, St. Aidan is truly one of the most beloved early saints of England and Scotland, he is often called “the Father of Northumbria” or “the Father of Northumbrian monasticism.” Owing to St. Aidan along with the holy kings Oswald and Oswin, the kingdom of Northumbria became a spiritual stronghold of the Anglo-Saxon lands. The saint’s activities yielded considerable results. St. Bede loved Aidan and appreciated him for his love of prayer, wisdom, peacefulness, purity, humility, and care for the sick and needy. Bede even pointed to the example of Aidan in order to reprimand some of the negligent bishops of his age.

Let us note that Aidan was an adherent of Irish practices in the ascetic life and the preaching of the Word of God. There were two active Christian missions at the time of St. Aidan: the so-called Roman Orthodox mission consisting of disciples and successors of St. Augustine of Canterbury in the south and the Celtic mission of St. Aidan and (later) his disciples in the north, which quickly moved further to the south, to Mercia and other regions. Thanks to both these missions, all England was brought to Christ within a relatively short period of time; and later in the same seventh century such saints as Cuthbert of Lindisfarne united in themselves the “Roman” and “Celtic” traditions—the contemplative ascetic life with brilliant practical abilities. Remarkably, adherents of both (Roman and Celtic) Orthodox traditions —which, it should be said, did not contradict each other, but, rather, supplemented each other—respected Aidan and admired him for his inexhaustible missionary works.

After St. Aidan, Lindisfarne Monastery founded by him grew and developed, monks from Lindisfarne erected new churches and monasteries in many parts of England, and the Holy Island itself became a prominent and important center of learning, culture, anchoretic life, nurturing a host of saints of God, and becoming the greatest missionary center in Northumbria. Holy bishops, monks and hermits of Lindisfarne followed one after another. Many of them were missionaries and ascetics at the same time, devoting much time to evangelization and part of the time to quiet life in seclusion. This tradition of holiness continued until the second half of the eighth century. Due to its numerous holy monks, Lindisfarne has been called by some, “the English Athos”.

St. Aidan is usually depicted as a bishop holding Lindisfarne Monastery in his palm, also with a deer at his feet (according to tradition, once the holy bishop took pity on a deer that was being chased by hunters, and through his prayers the animal became invisible). He is also depicted holding a burning torch, giving a horse to a poor peasant, calming the storm at sea, and putting out fire by his prayers.

St. Aidan is the patron-saint of the English county of Northumberland. Many parish churches are dedicated to this saint. There is an ancient church dedicated to him in the large village of Bamburgh near Lindisfarne which attracts many pilgrims every year. The church stands precisely on the site of the original wooden church built by Aidan himself. The old wooden beam kept in the church is believed to be the same wonder-working prop on which the saint leaned before his death. The church chancel has a reredos which depicts scenes of the early saints of northern England. (There is also an effigy of Grace Darling among the decorations, a local heroine. G. Darling was daughter of a poor lighthouse-keeper on one of the Farne Islands. In 1838 in nasty weather she saw a terrible wreck when a paddle-steamer was stranded on the shore of a neighboring isle and broke in half. In spite of the risk to her life the young woman took a rowing boat and rescued some the crew and passengers. All the country was amazed at her heroic dead, but Darling died four years later of tuberculosis aged only 26. She is buried at the churchyard in Bamburgh).

On Lindisfarne, one of the most beloved pilgrimage sites of England, which attracts the faithful by its peaceful spirit, quiet, holiness, isolation and wildlife, pilgrims can visit the ruins of the medieval priory as well as the ancient Church of St. Mary the Virgin and the museum with the visitor center; there is also a modern statue of St. Aidan beside the priory ruins. Lindisfarne also has a small castle with gardens. The current population of the Holy Island is around 180 people, mainly fishermen. There are large breeding colonies of seabirds nesting on the shores of Lindisfarne. There is a group of smaller Farne Islands near Lindisfarne, at least two of them were inhabited by early English hermits as well. Churches dedicated to St. Aidan can also be found in the towns of Morpeth in Northumberland, Sheffield in South Yorkshire, Leeds in West Yorkshire, Kingston upon Hull in East Riding of Yorkshire, Billinge in Merseyside, Caythorpe in Nottinghamshire, as well as Basford, Nottingham and others. Outside England there are Catholic and Protestant churches in honor of St. Aidan in various countries, including the U.S.A, Canada and South Africa. The Russian Orthodox parish (the Diocese of Sourozh) in the English city of Nottingham bears the name of Sts. Aidan and Chad—which is right as these two saints were of the same spirit. An Antiochian Orthodox parish in the city of Manchester is dedicated to St. Aidan as well.

* * *

Let us now briefly remember the other saints of God whose life entirely or partly was connected with Lindisfarne, this great symbol of early Orthodoxy in the British Isles and the seedbed of saints.

St. Finan (commemorated on February 17 according to the old calendar), an Irishman, was a great missionary and successor of Aidan as abbot and bishop of Lindisfarne (651-661). He sent out missionaries to the kingdoms of Mercia and Essex, baptized King Peada of Southern Mercia (son of the pagan Penda) and all his servants and converted King Sigebert of Essex to Christ. On Lindisfarne he built a new Cathedral in the Irish style. During his zealous and fruitful episcopate, monasteries in Tynemouth, Gilling, Whitby and other places were established.

St. Colman (feast: February 18), also an Irishman, was the third bishop of Lindisfarne (661-664) and a strict adherent of the Irish tradition of asceticism, the calculation of Easter and other practices. Under him the missionary work of Lindisfarne monks flourished. Later he left England and returned to his native Ireland, where he founded two monasteries: on the island of Innisboffin for Irish monks and in Mayo for English monks; both of them existed for many years. He was greatly venerated for his ascetic life and piety, reposing in 676.

St. Tuda (feast: August 21) was an Irish monk who was consecrated bishop of Lindisfarne after St. Colman, but he died in 664 during the epidemic of plague that struck England at that time.

St. Eata (feast: October 26) was the first native of Northumbria to become Bishop of Lindisfarne. At a young age he became the disciple of Aidan on Holy Island. Later he led the ascetic life in Ripon in North Yorkshire and then became abbot of Melrose in Scotland. With time he became abbot and bishop of Lindisfarne for many years. In about 685 Sts. Eata and Cuthbert, who were friends, exchanged sees and Eata became Bishop of Hexham where he soon reposed and where his relics may still rest in the crypt of the church. St. Bede deeply venerated Eata, calling him “the kindest and simplest of people.”

St. Cuthbert (feast: March 20), the Wonderworker of all England, first joined the monastery at Melrose in Scotland and later moved to Lindisfarne, where he became abbot and, from 685, bishop. For seven years he lived as a hermit on Inner Farne. Cuthbert evangelized large areas of Northumbria, Yorkshire, parts of Cumbria and Scotland, founding many churches and monasteries. Known as great wonderworker, healer and consoler, he reposed in 687, and his relics are preserved at Durham Cathedral to this day. Over 135 churches are dedicated to him.

St. Edbert (feast: May 6) was a monk from Lindisfarne who became the successor of St. Cuthbert as bishop (687-698). He excelled in knowledge of the Holy Scriptures and was noted for his voluntary poverty, care for the needy and frequent solitary prayer on Farne. He uncovered the incorrupt relics of St. Cuthbert and was later buried in St. Cuthbert’s grave.

St. Edfrith (feast: June 4) was the successor of St. Edbert as Bishop of Lindisfarne (698-721). He especially venerated St. Cuthbert, arranged the restoration of the latter’s cell on Inner Farne and for two years copied and illuminated the famous Lindisfarne Gospels in honor of Cuthbert, which are real treasures of the early English Orthodox world (now kept at the British Library in London). His relics rested in Lindisfarne, and later in Chester-le-Street and Durham.

St. Ethilwold (feast: February 12) was a disciple of St. Cuthbert and prior at Melrose. In 721 he became bishop of Lindisfarne where he served for some 16 years. In memory of Cuthbert he made the jewel-encrusted leather covers for the Lindisfarne Gospels.

St. Billfrid (feast: March 6) was a hermit on Lindisfarne whose veneration as a saint and wonderworker began even in his lifetime. He was also a very skilled goldsmith and thus he bound St. Cuthbert’s Lindisfarne Gospels in gold, silver and gems. He was greatly venerated after his death (c. 758) and even appeared in visions to the faithful. His relics were afterwards translated to Durham.

St. Ethilwald (feast: March 23) first was a hieromonk in Ripon and later lived as hermit on Inner Farne in St. Cuthbert’s cell (687-699). Once his prayers saved the future abbot Guthfrid with monks from death during a storm. After Ethilwold, Cuthbert’s cell was occupied by another holy hermit named Felgild whose feast-day is unknown.

St. Ywi (feast: October 8) was a hierodeacon from Lindisfarne ordained by St. Cuthbert. Later he decided to dedicate his life to “wandering for Christ” in Brittany where he lived for many years, reposing in about 690. He worked many miracles before and after his death. In the 10th century monks from Brittany came with relics of St. Ywi to Wilton Abbey in Wiltshire, asking for financial help for their church, but the saint’s relics miraculously became immovable. So it was decided to keep them in Wilton forever.

St. Baldred (feast: March 6) first was a hieromonk in Lindisfarne. Later he lived as anchorite in Tyningham in Scotland, on a tiny isle of Bass Rock, and at Seacliff near North Berwick where his cave still exists. He was noted not only as hermit, but also as a fine preacher and abbot, reposing in 756. His relics were later translated to Durham Cathedral.

From a huge number of missionaries who were trained at Lindisfarne or elsewhere in Northumbria or were sent from there to preach in the lands to the south we must mention the following: St. Diuma (+ c. 658, feast: December 7) who became the first missionary in Mercia and was Bishop of the Mercians and Middle Angles, establishing his see in Repton in Derbyshire. Diuma founded a monastery of St. Peter in Peterborough in Cambridgeshire and tirelessly preached Christ, reposing in Charlbury near Oxford, where he built a church and where his relics still may rest under the floor of St. Mary’s Church. St. Betty (+ c. 655, feast unknown) who preached in Mercia and founded a church or monastery in Wirksworth in Derbyshire where the decorated lid of his Saxon coffin is preserved inside the local parish church. St. Wilfrid (633-709, feast: October 12) founded many churches and monasteries in England and played an important role in the establishment of the Church in the country. In the north he served as Bishop of York and later of Hexham and founded the monastery in Ripon and a splendid church in Hexham; in Mercia he served as Bishop of Leicester, establishing monasteries at Oundle in Northamptonshire, Wing in Buckinghamshire (where an early English church still stands), Evesham in Worcestershire, Withington in Gloucestershire and Brixworth in Northamptonshire (where a finely preserved Saxon church built by him still exists together with a preaching cross); in the south Wilfrid preached in Sussex and the Isle of Wight, with his main center in Selsey, since then he has been venerated as the apostle of Sussex; he also actively preached abroad, especially in Frisia. The holy brothers Cedd (+ 664, feast: October 26), Chad (+ 672, feast: March 2) and Cynibil (feast: March 2) evangelized a great part of central England. St. Cedd established a monastery in Lastingham (Yorkshire, where his relics rest in the St. Mary’s Church) and later became Bishop of Essex, where he erected a monastery in Tilbury and many churches, the most famous of them being the chapel at Bradwell-on-Sea which still stands relatively intact. St. Chad was Abbot of Lastingham and later Bishop of Mercia with his center in Lichfield, Staffordshire. A great wonderworker and visionary, St. Chad was very close to the spirit of Aidan, practicing the Irish tradition and preaching the example of the apostles. For about three years of his short episcopacy Chad enlightened an enormous region stretching from Cheshire and Shropshire in the west to Lincolnshire in the east, founding dozens of churches and several monasteries, for example, at Barrow on Humber in Lincolnshire. His relics are kept at the Roman Catholic Cathedral in Birmingham. St. Edfrid (+ c. 675, feast: October 26) was a priest from Northumbria who preached Christ in Mercia and founded the first monastery at Leominster in Herefordshire. St. Theoc (the seventh century, no feast-day) was probably a Northumbrian monk who lived as hermit in Gloucestershire and on the site of his spiritual labors the famous Tewkesbury Abbey of St. Mary the Virgin was built, which still exists. St. Ceolwulf (+ 764, feast: January 15) was King of Northumbria (729-737). He promoted monastic life in his kingdom and it was he to whom St. Bede dedicated his Church History. He ended his days as a simple monk in Lindisfarne. And, finally, there were two more hermits associated with the site who lived much later: they are Godric and Bartholomew. Though they lived after the Norman Conquest and officially belonged to the Roman Catholic Church, according to their lives, they inherited much from the true Orthodox tradition. Godric (c. 1065-c. 1170) was born in Walpole in Norfolk. He was a merchant and a sailor as a young man. After a pilgrimage to the Holy Land he visited Lindisfarne in his native England where St. Cuthbert appeared to him in a vision. From that moment he decided to live as hermit. So he built a tiny hermitage near present-day Finchale near Durham and lived there for 60 years in unceasing prayer and spiritual exploits. He healed many sick people who flocked to him, composed hymns to the Mother of God and cared for wild animals. After his death a monastery was founded in Finchale whose ruins are visited by pilgrims to this day. Bartholomew (+ c. 1193) was born Tostig in Whitby. He travelled widely in Europe and finally became a monk in Durham taking the name Bartholomew. After a vision of St. Cuthbert he retired to St. Cuthbert’s cell on Inner Farne, where he lived for over 40 years as a true anchorite.

Holy Hierarch Aidan and all the saints of Lindisfarne, pray to God for us!