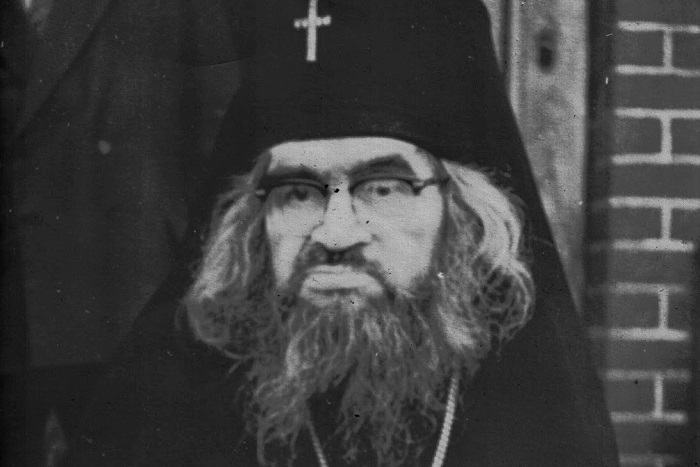

St. John believed that, in whatever land an Orthodox Christian found himself, it was his responsibility to venerate and pray to its national and local Saints. Wherever St. John went—Russia, Serbia, China, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, Tunisia, America—he researched the Lives of the local Orthodox Saints. He went to the churches housing their relics, performed services in their honor, and asked the Orthodox priests there to do likewise. By the end of his life, his knowledge of Orthodox Saints, both Western and Eastern, was seemingly limitless.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about St. John’s life is that he manifested in himself so many different kinds of sanctity. It was as if, through the intense study of the Lives of the Saints that he had undertaken in his early years, he had internalized and made his own the whole realm of Orthodox sanctity, in all its varied forms. He was a true student of the Saints, one who sought to follow

in their footsteps, and thus to follow in the footsteps of Christ. By living like the Saints, he became one of them.

in their footsteps, and thus to follow in the footsteps of Christ. By living like the Saints, he became one of them.

Let’s look at some of the varied forms of sanctity that could be seen in Archbishop John:

1. He was first of all a great ascetic in the tradition of the monastic Saints of old, such as St. Macarius the Great, St. Pachomius the Great, and others.

2. He was a clairvoyant reader of hearts, and one who could identify and name people he had never seen before. Enlightened by the Grace of God, he could hear and answer people’s thoughts before they expressed them. He also foretold the future, including the time of his own death. In this way, he was very much in the tradition of the great monastic elders of the past, especially the clairvoyant Russian elders such as those of Optina Monastery.

3. He was an almsgiver in the tradition of St. Philaret the Almsgiver, St. John the Almsgiver, etc. We have seen how he sacrificed himself for orphaned children, going himself into dangerous slums and houses of prostitution in order to rescue children from starvation or unhealthy environments. He was constantly giving to and working to help the needy. He himself wore clothing of the cheapest Chinese fabric. He often went barefoot, sometimes after having given away his sandals to some poor man.

4. He was a hierarch and theologian, a Church writer and apologist who defended the Church against error, much in the tradition of St. Athanasius the Great, St. Gregory the Theologian, and others. Besides his many published sermons, rich in theological content, he wrote valuable theological treatises in order to defend traditional Orthodox teachings which were being undermined in modern times.

One of these works, in which he presents the Orthodox teaching on the Mother of God in contrast to Protestant and Roman Catholic distortions, has been published in English. He also wrote an extensive essay pointing out the fallacies of the modern teaching of Sophiology.

5. He was an apostle, evangelist and missionary to new lands, in the tradition of Sts. Cyril and Methodius, St. Nahum of Ohrid, and others. When he was in Western Europe, he worked hard to establish indigenous Orthodox Churches in France and the Netherlands: churches made up of the native peoples of these lands who had converted to the Orthodox Faith. He understood that the Orthodox Church is universal, and he said that the Orthodox Gospel of Christ must be spread throughout the world. Later, when he came to America, he instituted English Liturgies in addition to Slavonic Liturgies, in a Cathedral that had only known Slavonic Liturgies. He blessed and supported our newly begun St. Herman Brotherhood, which was dedicated to bringing Orthodoxy to the English-speaking world.

6. He was a healer and miracle-worker, in the tradition of St.Martin of Tours, St. Nicholas of Myra in Lycia, and others. Through his prayers, he healed people of almost every imaginable malady; and he continues to do so after his repose.

7. He was a loving and self-sacrificing pastor, in the tradition of St. John of Kronstadt and all the other hierarch and priest Saints of ages past. So great was his love that everyone felt that he or she was his “favorite.” He was overflowing with self-sacrificing love for his flock, and for those outside of his flock as well, such as a dying Jewish woman whom he suddenly healed with the words “Christ is Risen.”

8. He was a deliverer of people from captivity, in the tradition of St. Moses the God-seer and St. Paulinus of Nola. As we have seen, he brought 5,000 Orthodox believers out of Communist China and into freedom in America.

9. Finally, he was to a limited degree a fool-for-Christ in the tradition of St. Andrew the Fool-for-Christ and others. He could not be a fool-for-Christ in the full sense of the term, since this would compromise the dignity of his hierarchical office. And yet at many times he did things which were at odds with the ideas of the world, and thus he evoked censure from people who did not see him for what he was: a man of God. He was criticized, for example, for going about barefoot, and for wearing a collapsible cardboard mitre that had been lovingly made for him by his orphans.

We have now looked at nine different types of sanctity manifested in this one Saint, St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco. Nine types which he had learned about through his study of the Lives of the Saints.

What the contemporary hagiographer Constantine Cavarnos says of modern Saints in general applies perfectly to St. John: “Modern Saints admire and imitate the older ones: they follow closely their example, study their teaching carefully, and—what is extremely significant—they confirm it. Those of the modern Saints who write or preach amplify and illustrate the teaching of the older Saints, and relate it to modern realities.”

* * *

St. John believed that, in whatever land an Orthodox Christian found himself, it was his responsibility to venerate and pray to its national and local Saints. Wherever St. John went—Russia, Serbia, China, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, Tunisia, America—he researched the Lives of the local Orthodox Saints. He went to the churches housing their relics, performed services in their honor, and asked the Orthodox priests there to do likewise. By the end of his life, his knowledge of Orthodox Saints, both Western and Eastern, was seemingly limitless.

Here is a story which illustrates St. John’s love for the Saints, and how he went out of his way to learn about them and venerate them:

One of St. John’s spiritual children was Archimandrite Spyridon, who later became the father confessor of our monastery in the 1970s. Like St. John, Fr. Spyridon was born in Russia, but went to Serbia following the Russian Revolution. He knew St. John from a young age, when St. John was still studying at the University of Belgrade.

When Serbia fell to the Communists, Fr. Spyridon and many of his fellow Russians settled on the border of Italy and Serbia, in a refugee camp in the Italian city of Trieste. Fr. Spyridon was ordained to the priesthood in 1951 and was assigned as a pastor of the camp church in Trieste.

At this time, St. John had just been assigned as the Bishop of Western Europe, and so he would visit Fr. Spyridon and his flock in the refugee camp in Trieste. When St. John came to the place where Fr. Spyridon served, he was already fully informed about the early Western Saints of Trieste—such as Justus the Martyr, after whom the city had originally been called Justinopolis, St. Sergio the Martyr, and St. Frugifer, the first bishop of Trieste. Finding that nothing had been done to venerate the local Saints, Archbishop John was disappointed.

Fr. Spyridon later said how he regretted not having thought of it before. No one had done such a thing: the Saints of Trieste had largely been forgotten, and it was St. John who restored their local veneration. Before doing anything else in Trieste, he took Fr. Spyridon to the relics of the Saints, vested in an epitrachelion and a small omophorion. With a censer and a cross in his hand he descended into the crypts under cathedrals where, according to his long lists of information, the Saints had been buried. He sang troparia and kontakia written on pieces of paper which he pulled out his pockets, imploring the Saints to intercede for the city. And only then did he go to celebrate the services in Fr. Spyridon’s camp church.

As Fr. Spyridon recalled, St. John acted as if the ancient local Saints were present wherever he walked. Before leaving Trieste, he contacted local Roman Catholic clergy, acquiring from them various permits so that the Orthodox church in Trieste would have free access to the relics and sites of the Saints. Then he gave Fr. Spyridon strict instructions on how to commemorate the Saints, how he should take his parishioners to the shrines of all local Saints on their feast days, venerate them, sing services to them, and so on. St. John said that no services should be conducted without first addressing these local Saints, and no Liturgies performed without first commemorating them at the proskomedia.

While in Western Europe, St. John collected the Lives and icons of Orthodox Saints from many different Western European countries, who lived before the time of the schism of the Latin Church. Since most of these Saints were included in no Orthodox Calendar of Saints, St. John compiled a list of these Saints with information about their lives, and submitted this to his Synod of Bishops for inclusion in the Orthodox Calendar.

Since he was an Apostle of Christ, St. John called upon each local Saint he learned about to provide heavenly help in evangelizing new lands. As Archbishop of San Francisco, he called upon all the Saints of America, including the most local of all Saints, the Native American St. Peter the Aleut, who was martyred in California.

Archbishop John had an especially great devotion to St. Herman of Alaska as a patron of the American Orthodox mission. He sought to have St. Herman canonized, and this occurred four years after St.John’s repose, in 1970.

On June 28, 1966, St. John came to the Orthodox bookshop in San Francisco that had been started with his blessing by our St. Herman Brotherhood. After he had blessed the shop and printing room with the miracle-working Kursk Icon of the Mother of God, he proceeded to talk to the brothers about Saints of various lands. As Fr. Seraphim Rose later recalled: “He promised to give us a list of canonized Romanian Saints and disciples of Paisius elichkovsky. He mentioned having compiled (when in France) a list of Western pre-schism Saints, which he presented to the Holy Synod.”

In particular, St. John talked to the brothers in the shop about St.Alban, the first martyr of Britain. Out of his little portfolio he pulled a short Life of the Saint, together with a picture postcard of a Gothic cathedral in the town of St. Albans near London, in which the Saint had been buried. St. John looked into the brothers’ eyes to see if they got the point. St. Alban, like most of the Saints of Western Europe, was not in the Orthodox Calendar; and St. John was letting them know that he should be venerated by Orthodox Christians, especially in English-speaking lands.

This turned out to be St. John’s last contact with the shop and our Brotherhood while he was alive on this earth. Four days later he reposed in Seattle.

Right after St. John’s repose, Fr. Seraphim wrote in his Chronicle of our Brotherhood: “Amid the talk of the ‘testament of Vladika John,’ what has our Brotherhood to offer? This seems to be clearly indicated both by our very nature and by Vladika John’s instructions to us. On his last visit to us especially, he talked of nothing but Saints—Romanian, English, French, Russian. Is it not therefore our duty to remember the Saints of God, following as closely as possible Vladika’s example? I.e., to know their Lives, nourish our spiritual lives by constantly reading them, making them known to others by speaking of them and printing them—and by praying to the Saints.”

This, then, is St. John’s testament to our Brotherhood, and I believe to all Orthodox Christians: To remember the Saints of God.

St. John himself wrote beautiful words about the Saints. These words well express what he saw as the essence of sanctity, as well as the blueprint of his own life. “Holiness is not simply righteousness,” St. John wrote, “for which the righteous merit the enjoyment of blessedness in the Kingdom of God, but rather it is such a height of righteousness that men are filled with the Grace of God to the extent that it flows from them upon those who associate with them. Great is their blessedness; it proceeds from personal experience of the Glory of God. Being filled also with love for men, which proceeds from the love of God, they are responsive to men’s needs, and upon their supplication they appear also as intercessors and defenders for them before God.”