This article is devoted to anathema – the excommunication from the Church of a person or groups of persons and the prohibition for them to participate in the Sacraments and prayerful fellowship because of heresy, serious unrepentant sins, schism, and threat to Christian unity. What is the purpose of ecclesiastical excommunication? What is the difference between a great and a small excommunication? Who can declare it and who can remove it? What are the most famous cases of excommunication from the Church in general and from the Russian Church in particular? This article will address these and other questions.

Anathema in the Bible

Anathema (Greek: ἀνάθεμα/ἀνάθεμα “excommunication”) is a word of Greek origin. For the Ancient Greeks it meant “something dedicated to God, an offering to the temple, a gift” (Homer, Herodotus, Sophocles), i. e., it used to speak more about the sacramentality of an object excluded from the everyday use. It was this initially positive term that the translators of the Septuagint used to translate the Hebrew word חרם (herem), which had both positive and negative connotations. On the one hand, the word herem signified something set apart from human possessions to be dedicated to God (fields, cattle, slaves), and such a gift to God was considered to be an offering and was called “most holy unto the Lord” (Leviticus 27:28), and the term “holiness” itself was also understood as something votive and sacred.

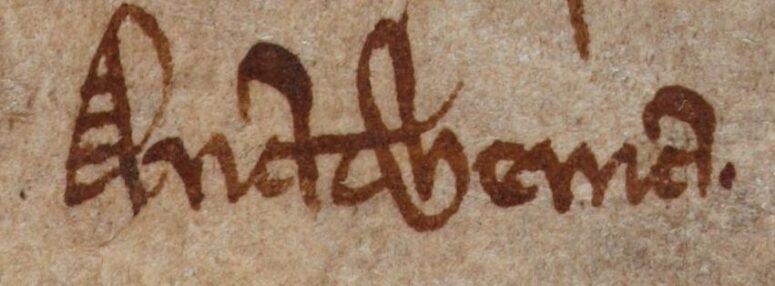

However, the things that were dedicated to God had to be destroyed in some cases. Numbers 21:2-3: And Israel vowed a vow unto the Lord, and said, If thou wilt indeed deliver this people into my hand, then I will utterly destroy (the Masoretic text uses weharamti, a word that is related to the root חרם meaning something that is cursed or destroyed) their cities.” Enemy towns and enemy weapons that were considered unclean and could not be used by Jews were cursed and therefore subject to destruction in Old Testament times, so the word herem began to mean something cursed, rejected by people, and doomed to destruction. The word anathema thus received a sharply negative connotation, and it is with this meaning that we find it in the Epistles of the Apostle Paul (1 Cor. 12:3; Gal. 1: 8-9; Rom. 9:3). In 1 Corinthians 16:22, the Apostle Paul uses a special formula, which appears to be a spell, If any man love not the Lord Jesus Christ, let him be Anathema Maranatha. The Aramaic word maranatha (the Lord is near) in this context implies delegating the excommunicated, cursed man to the judgment of the coming Messiah.

Anathema in the Early Church

According to St. Epiphanius of Cyprus (†403), the term ἀποσυνάγωγος (John 9:22) may be regarded as a prototype of the anathema. It meant the excommunication from the synagogue, which was applied in particular to the followers of Jesus (Adv. haer. 81). Excommunication in the Church practice was imposed on followers of various heresies, schismatics, as well as violators of the Church discipline and Christian morals on the basis of the Apostle Paul’s use of this term in his epistles. The term anathema was first used in the canons of the Synod of Elvira (c. 313), and, starting with the Synod of Gangres (c. 340) and subsequent synods, the wording for the anathema “if anyone… let him be anathema” became standardized. For instance, St. Cyril of Alexandria (†444) wrote twelve doctrinal theses against the teachings of Nestorius, and each thesis was concluded by an anathema, that is, by the excommunication of all those who do not subscribe to these theses. Since the fifth century, there has been a formal distinction between the anathema (great excommunication), i. e., a complete and collectively approved excommunication from the Church, and a small excommunication (ἀφορισμός), which was temporary and consisted of depriving a member of the Church of the right to participate in the Eucharist until the completion of the penance, but with the preservation of their membership and their prayerful fellowship with the faithful, as well as letting them receive pastoral blessings.

Meaning of the Anathema

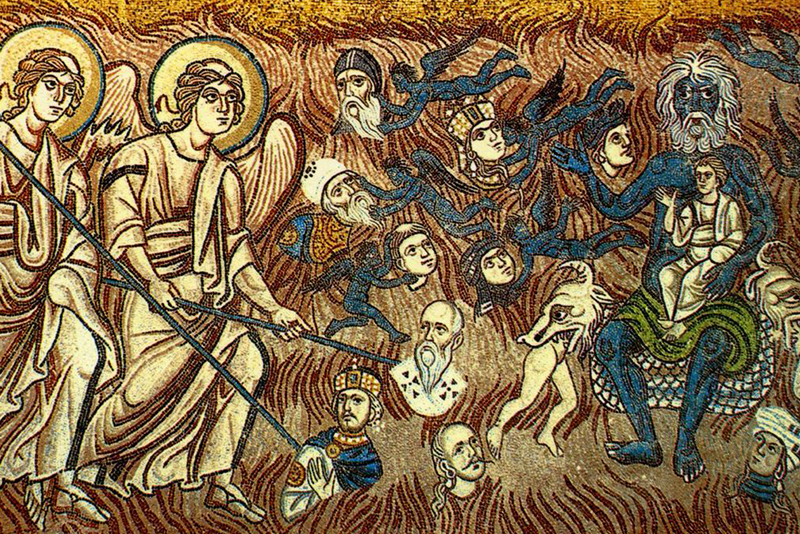

The basis for the anathema is the following statement of Christ, [I]f he neglect to hear the church, let him be unto thee as an heathen man and a publican (Matthew 18:17). Excommunication as a phenomenon of church life remains a complex and ambiguous problem, and its enforcement should always be subject to strict and comprehensive scrutiny of the designated Church authority. The imposition of anathema can only be justified if a person or group of people who are being excommunicated threaten the doctrinal purity of the Christian community, its integrity and moral health by their worldview or actions. This attitude towards excommunication as the most extreme and severe punishment arose in the Church under the influence of the Apostle Paul, who once offered the Church of Corinth “to deliver unto Satan”, i.e., to anathematize someone who “has his father’s wife” (1 Corinthians 5:1). Paul added that such an act would destroy his flesh but save the sinner’s spirit when the Lord comes (see 1 Corinthians 5). Over time, however, this somewhat obscure passage from the Scripture was interpreted as the final condemnation of man to the curse and the handing him over to Satan, which became particularly common during the early Middle Ages, both in the West and in the East. This view on excommunication as an irrevocable punishment is shared by the author of the treatise That Neither The Living Nor The Dead Should Be Anathematized (PG. 48. Col. 945-952), previously attributed to St. John Chrysostom. The author, citing the Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:30-37), considers anathema unacceptable and contrary to the basic law of Christianity about love for others, regardless of their doctrinal beliefs. The author of the treatise believes that excommunication should be declared only against false doctrines, but not against the people who adhere to them so that they do not lose hope for salvation. Only the Lord can judge people, and those who anticipate His judgment and condemn people to eternal perdition will themselves be severely punished as usurpers of God’s power (PG. 48, Col. 948). Patriarch Theodore Balsamon, a prominent expert in canon law, also shared this position on anathema.

Still, the practice of anathema was actively used in church life to fight heresies in order to protect Orthodoxy and religious identity. The Councils affirmed and formulated Orthodox dogma on the basis of Scripture and the writings of the Holy Fathers, while condemning and exposing the falsehood of wrong doctrines. These doctrines, as well as their originators (heresiarchs), were excommunicated, but the heretics themselves, provided their public repentance and confession of the right faith, could be reintegrated into the Church. Orthodoxy treats anathema as a very painful but effective remedy, which is designed to make the person who has gone astray rethink his ways, as well as to warn other Christians against making such mistakes and engaging in false thinking.

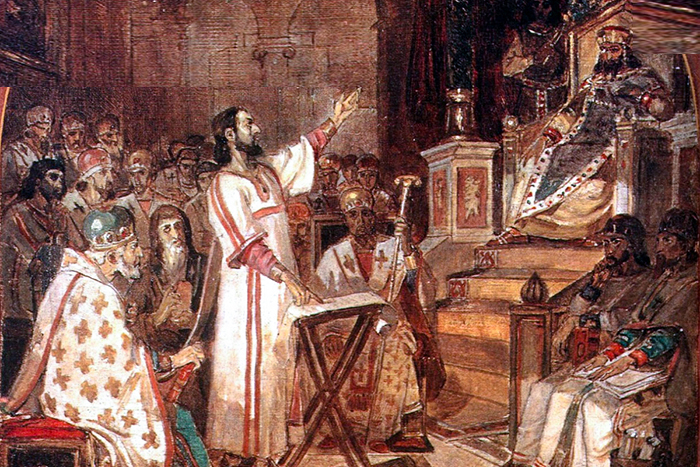

The Declaration of Anathema

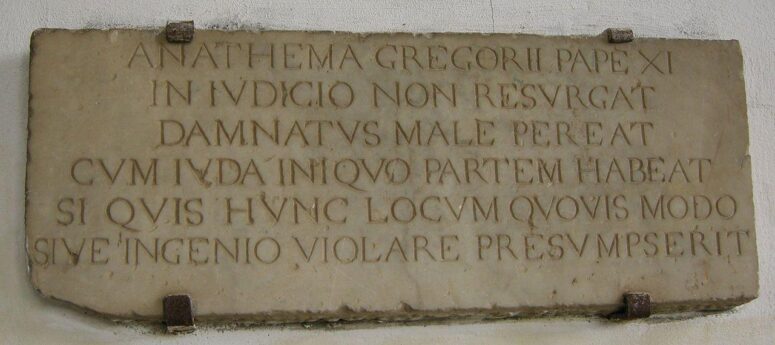

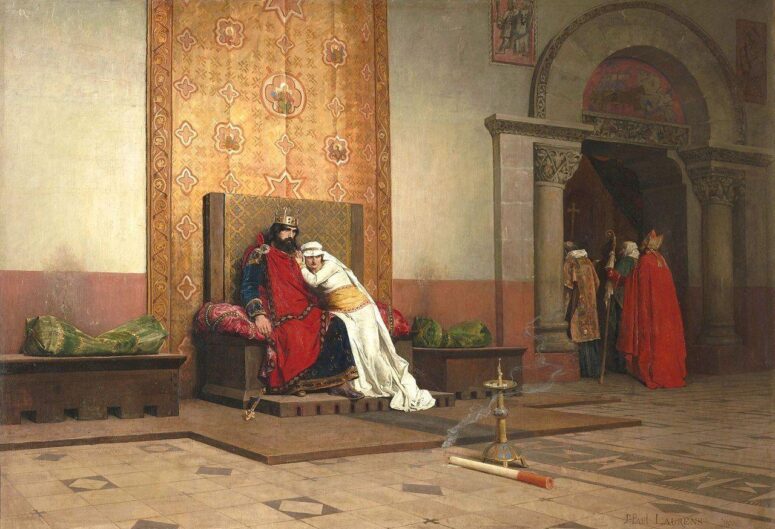

Declaring anathema to someone is the ultimate and last measure of canonical penance, so this power can only be wielded by an assembly of bishops, the Synod headed by the Patriarch, and in particularly complex and global cases the Local Council or even the Ecumenical Council. When the Patriarchs alone decided to anathematize someone, they normally sought support for their decision from other bishops in order to give this act a more collegial character. There is a known case from the life of St. John Chrysostom (†407), who, being already Archbishop of Constantinople, refused to single-handedly condemn the supporters of Origenism and the followers of Dioscorus, Bishop of Hermopolis, and insisted that a council be convened to investigate and resolve this issue (Socr. Schol. Hist. eccl. VI 14. 1-3). According to the Charter of the Russian Orthodox Church, an anathema may be imposed only by the diocesan bishop or the Patriarch of Moscow together with the Holy Synod and only “upon the recommendation of an ecclesiastical court” (Charter, 2000. VII 5). If the excommunication is imposed after death, it means a ban on the commemoration of the deceased, panikhidas and the reading of absolution prayers by the priest. The wording of the excommunication is as follows: “Let Name be anathema” (that is, let him be excommunicated), or “I hereby anathematize Name and/or his heresy”. In the West, there existed for some time a special rite of excommunication, during which the bell rang, after which the divine book (a symbol of the Book of Life) was slammed before the convict, and clerics extinguished candles and threw them on the ground. There is a special rite in the liturgical tradition of the Orthodox Church, called the Triumph of Orthodoxy, held once a year on the first Sunday of Lent. It is the only time of the year when one can hear the proclamation of anathema to ancient heresies. The rite developed after the victory of Orthodoxy over iconoclasm in the ninth century and is still held up to this day in cathedrals and large monasteries. One of the most recent known cases of anathema in the Russian Church was the excommunication of Philaret (Denisenko), the former Metropolitan of Kiev and a contender for the Patriarchal Throne, in 1997. The Patriarch of Constantinople removed the anathema in 2018, but it has not yet received all-Orthodox approval.

Lifting the Anathema

Anathematization of a person is not an irrevocable act that shuts down the condemned person’s way back to the church, and therefore it does not take away that person’s hope for salvation. The main condition for the removal of excommunication is the person’s heartfelt repentance and improvement of both his life and his confession of faith. If the previously excommunicated Christian or religious community no longer pose a threat to the unity of the Orthodox Church, and their fellowship with the faithful will not cause temptation, then the Church authority that imposed the previous penance, after careful consideration of the case, has the power to remove the anathema and restore full communication with the members of the Church who previously seceded from the Church. The right to receive appeals and to restore the excommunicated clergy also belongs to the Ecumenical Patriarch who is the first by honor, according to the canonical rules (Rules 3, 4, and 5) of the Council of Serdica (†343). Originally it was the Pope’s right, but since the Patriarch of Constantinople took his place in the diptychs, this right has been appropriated by him. In order to avoid abuse, the lifting of excommunication and the reinstatement of the clergy by the Ecumenical Patriarch as part of the appeal process must be approved by other Local Churches. The most famous case of the removal of mutual anathemas took place in Jerusalem in 1964, when Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople canceled the anathema of 1054, which did not solve the dogmatic differences but promoted amicable and constructive dialog. The removal of the anathemas against Old Believers by the Council of 1971, which abolished the anathemas of the Moscow Council of 1667, was a momentous act for the Russian Church. It facilitated the return of Old Believers to the canonical Church, as well as allowed the Church itself to serve according to the Old Rite.

Therefore, the anathema is the separation from the Church of a person who sank into heresy or schism for the sake of safeguarding and preserving the purity of the Church community. It is also an act of healing that protects the Church and warns the condemned person that he or she is on the wrong path that leads him or her away from Christ. The Church can resort to this terrible punishment very cautiously and after a thorough investigation of the case, bearing in mind that there have been some dark pages in the Church history, when the Church authorities employed anathema more for political than ecclesiastical reasons, as well as deprived of ministry and sent into exile such great saints and preachers as St. John Chrysostom. While anathema excommunicates man from the Church, we should remember that the final judgment always rests with the Lord God, who alone knows the hearts of men.

Hopefully, no one today should ever have to be highly knowledgeable about this topic, but it is always important to know one’s faith, the history of one’s Church, so that one does not inadvertently fall into any delusion or schism, which, unfortunately, has become increasingly common in recent times. By relying not on ourselves but on the testimonies of the saints, we, by the grace of God, will be members of the body of Christ until the end.