The People of God have long been accustomed to the titles, ascriptions, and even historical settings that preface various of the Psalms. Sometimes, in fact, these “Psalm Inscriptions” are the object of properly theological interest, not only in commentaries on the Psalter, but also in separate works. The most famous among the latter, arguably, are two treatises of St. Gregory of Nyssa, who found in the Psalm titles a coherent, systematic treatment of ascetical theology.

Because these inscriptions are not normally considered integral to the inspired text, their study pertains to exegetical — not canonical — history.

The dating of them has not been convincingly fixed, but generally they are described as “late,” meaning anytime between the Exile and the Septuagint — the early fifth through the late fourth centuries. It is difficult to demonstrate, on the other hand, that all this material necessarily came from the same period and provenance. Indeed, I am persuaded that it did not.

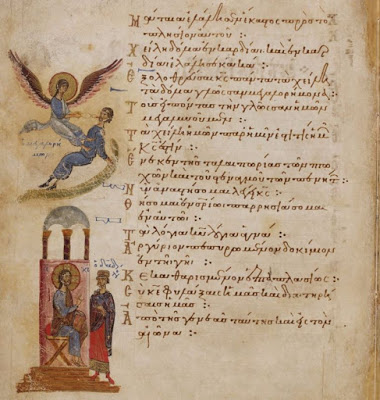

David’s name appears more often than any other in the Psalm inscriptions — 73 times. Of these, fourteen instances ascribe individual psalms to specific episodes in David’s life.

The most notable of these, surely is Psalm 51 (50), the Miserere, which is ascribed to the occasion when David received a word or two from the prophet Nathan — some business about adultery and murder, if memory serves.

Of the fourteen inscriptions that assign individual psalms to specific occasions in David’s life, nine are related to the period of his exile as a fugitive from the insane wrath of Saul.

These assignments, which are rather imaginative, can be strung together, related step-by-step to episodes during David’s time of desert exile. They are worth listing in the historical sequence in which they appear in 1 Samuel 19-31.

In this arrangement, the first assignment is Psalm 59 (58), which its inscription relates the very beginning of David’s exile: Saul’s officers watching through the night, planning to arrest him in the morning (1 Samuel 19:11-12).

The second is Psalm 56 (55), assigned to David’s seizure and temporary detainment by the Philistines (21:10-15).

This incident is also the assigned setting of the third example, Psalm 34 (33), but here there is a historical problem: Whereas David plays an idiot before Achish in the scene in First Samuel, this psalm title speaks of “Ahimelech,” an obvious confusion. The mistake prompts me to think a different — less careful — scribe was responsible for this inscription.

The fourth example, Psalm 142 (141), places David “in the cave.” This appears to be the cave of Adullam in 1 Samuel 22:1.

The fifth example relates Psalm 52 (51) to the treachery of Doeg the Edomite (22:9-19), who is thus identified as the boastful man with the vicious tongue. This assignment is probably the most persuasive.

The sixth example is Psalm 54 (53), the inscription of which relates it to David’s betrayal to Saul by the Ziphites (23:14-23).

The seventh example, Psalm 57 (56), is tied to David’s “close call” with Saul in the cave near Engedi (24:3-8).

The eighth example, which places David “in the wilderness of Judah,” is Psalm 63 (62). The assignment is apparently a general reference to this whole period of David’s life.

The final example, Psalm 18 (17), celebrates the end of David’s exile, when Saul is slain in the Battle of Mount Gilboah. The text of this psalm is virtually identical to 2 Samuel 22.

One is impressed that nine of these fourteen biographical references are assigned to a relatively short period in David’s life: the time of his desert exile. One is also struck that six of them are found in the “second book” of the Psalter, clustered between Psalms 52 and 63 (51 and 62). Five of those are assigned to discrete incidents within 1 Samuel 19-24. At least five of them, and perhaps six, appear to come from the same hand, which means that they appeared at the same time in a particular manuscript of the second book of the Psalter.

The impulse prompting that early copyist to make these biographical references is a matter of speculation, but surely the proper path in this speculation is to consider what those references did, in fact, achieve. There are two things, I believe.

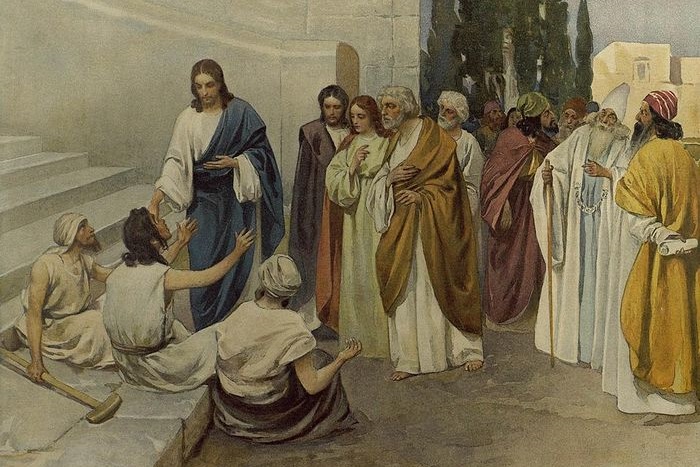

First, by assigning these particular psalms — I have in mind those clustered in the second book of the Psalter — to the period of David’s persecution and distress, our scribe effectively identified the suffering just man, a very prominent a figure in the Psalter, with the Anointed One. In other words, the Lord’s Suffering Servant was made identical to the Lord’s Messiah.

Except for the incident of Absalom’s rebellion (the assignment of Psalm 3), the period of David’s desert exile offered that ancient copyist the most persuasive opportunities to make that identification.

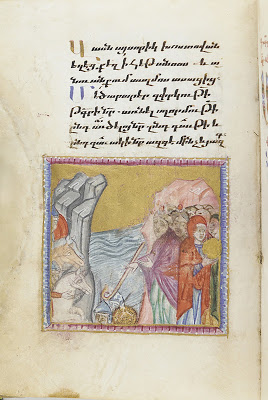

Second, our scribe’s interest in the period of David’s wandering in the desert evokes a comparison with Israel’s corresponding experience during the years following the Exodus. In the Psalter, this latter period receives extensive consideration (cf. Psalms 78 ([77], 95 [94], 105 [104], 106 [105], etc.).

Such a comparison, however, serves mainly to highlight a contrast: Whereas Israel, during its forty years in the desert, was repeatedly unfaithful to the Lord, David was entirely faithful during his desert sojourn. Tempted, in several instances, to assert his own will and take the future into his own hands, the Suffering Servant consistently surrendered his destiny and placed his soul in the hands of God.

This contrast will later appear in those Gospel scenes where Jesus, the true Messiah and Suffering Servant, is tempted, as Israel in the desert was tempted of old. Like David, He remains faithful. We also know Jesus’ fondness for that period of David’s life (cf. Luke 6:1-5).