From “The History of Vestments”

It is with the omophorion that we come to one of the most debated topics in the study of liturgical dress, that of the origin of the specific “garments of office” for the major orders of the clergy. For in addition to their sticharion or phelonion, each order (that is, deacon, presbyter, and bishop) has a corresponding “scarf of office”: the orarion, epitrachelion, and omophorion. Most writers on this subject are at a loss to determine definitively the origins of these garments due to the lack of references in ancient texts and the often obscured, draped fabric folds depicted in iconography, ivory carvings, and mosaics. However, from a study of pre-Christian garments, Byzantine statecraft, and various ancient artworks, including early mosaics and consular diptychs, along with an understanding of the tailoring methods of producing these items, one may reach the conclusion that these three garments have their origin in two historical garments, namely the toga and the pallium, both of which had an either exclusively (in the case of the toga) or a primarily (in the case of the pallium) ceremonial or formalusage for at least two hundred years prior to the standardization of Orthodox Christian vestments.

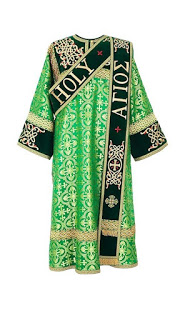

To begin with the deacon’s orarion, this garment is a long, narrow band, usually five to seven inches in width, which is worn over the sticharion, suspended from the left shoulder and while I have expended much effort in finding firm correlations, absolute confirmation continues to elude me in the shadows of history, and so I must be clear that these are purely my own theories, some supported by respected authors on the subject, such as Duchesne and Legg, and others not extending to the hem of the sticharion both in front and in back (the additional length wrapped around the torso and over the right hip, as is now in use in the Greek tradition, seems to be a later addition, and its initial use could have been reserved to archdeacons). In its general design the orarion is a very long rectangle, approximately nine feet in length (fifteen feet with the Greek hip loop).

Some authors have attempted to trace its origins to the imperial “handkerchiefs” distributed by Aurelian to be waved in approval at the theatre or circus. According to this attribution the garment would carry, despite its imperial gifting, connotations of worldliness and entertainment, both of which ideas are strongly at odds with the deacon’s primary role of service at the Divine Liturgy, such service being associated with the ministry of the angels in heaven. Several writers have tried to bolster the supposed connection of the orarion with Aurelian’s handkerchief on the basis of speculative etymology. “Os” is Latin for “mouth” or “face,” which some have taken to refer to the use of a scarf to wipe the face, thus suggesting that the orarion begins its liturgical service as a glorified napkin or sweat cloth. Such explanations might well strike one as insufficient and slightly ridiculous.

Previously we have noted the importance of studying the fundamental design of a garment when attempting to determine the origins of a particular piece of Orthodox liturgical vesture. A long, rectangular garment used for a formal purpose is more satisfactorily found in the ancient pallium, which we have previously seen was reserved for dignified settings and thus is far more appropriate in both its design and usage for the Divine Liturgy. As with most cloak-like garments, the pallium had two methods of wear: the first being to wrap the garment around the shoulders letting the ends hang down the front of the body; the second being to wrap the garment. The question of the source of the word “orarion” is a linguistic puzzle which is fascinating in its own right and may, or may not, shed light on the origins of the garment thus named. In addition to a derivation from “os,” it has also been suggested that the name could derive from the Latin “hara” (referencing the deacon leading prayers at the services of the hours) or simply from the Latin verb “orare,” meaning “to pray,” and in this understanding could well have the meaning “the item one prays with,” establishing it as a liturgical scarf of office and thereby differentiating it from a ceremonial or court scarf of office.

Previously we have noted the importance of studying the fundamental design of a garment when attempting to determine the origins of a particular piece of Orthodox liturgical vesture. A long, rectangular garment used for a formal purpose is more satisfactorily found in the ancient pallium, which we have previously seen was reserved for dignified settings and thus is far more appropriate in both its design and usage for the Divine Liturgy. As with most cloak-like garments, the pallium had two methods of wear: the first being to wrap the garment around the shoulders letting the ends hang down the front of the body; the second being to wrap the garment. The question of the source of the word “orarion” is a linguistic puzzle which is fascinating in its own right and may, or may not, shed light on the origins of the garment thus named. In addition to a derivation from “os,” it has also been suggested that the name could derive from the Latin “hara” (referencing the deacon leading prayers at the services of the hours) or simply from the Latin verb “orare,” meaning “to pray,” and in this understanding could well have the meaning “the item one prays with,” establishing it as a liturgical scarf of office and thereby differentiating it from a ceremonial or court scarf of office.

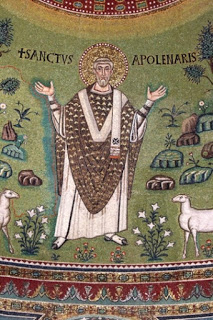

Around the front and back of the body, covering one shoulder completely and fastening at the other shoulder with a pin orfibula. This latter style of wear is depicted on the courtiers in the Sant’ Apollinare mosaics, yet more evidence of the use of the pallium as a mark of office and service, since courtiers were servants of the imperial court, an earthly corollary to the office of the deacon at the Divine Liturgy. If we take the pallium thus worn sideways, fastening at the left shoulder, and abbreviate it to a narrow strip (a natural evolution from ancient forms of folding and draping garments so that only the decorative border would be displayed), we have a garment identical to the deacon’s orarion. While there is no conclusive evidence proving this origin of the orarion, this theory best answers the foremost questions of suitability of use and consistency of design. A mosaic from Sant’ Apollinare in Classe depicting courtiers wearing the pallium If the form of the orarion does indeed come from the abbreviation of the full pallium to its decorative border edging, then another source for the word “orarion” is suggested: “ora” is a Latin word meaning “border” or “edge.”

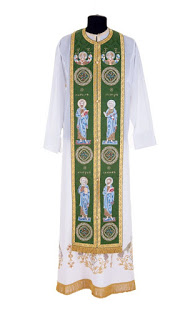

Moving on to the epitrachelion, the scarf of office of the presbyter, we may find its origins in the alternate wear of the pallium, that of suspending the garment around the shoulders and allowing the ends to hang down in front of the body. Once again, the pallium was associated with dignity and formality, as well as being the appropriate narrow, rectangular design, all of which points to the epitrachelion finding its origins in the pallium. (In the West the name of the historic pallium eventually came to be associated with a badge of archepiscopal office, a fact which further underscores its revered position in garment history.) As the noted liturgical scholar Duchesne observes, “In the last analysis this scarf [the pallium] was, no doubt, a relic of the short mantle which had been brought into fashion in the Roman Empire by the Greeks. But the discolora pallia of the Theodosian Code were evidently scarves,

Moving on to the epitrachelion, the scarf of office of the presbyter, we may find its origins in the alternate wear of the pallium, that of suspending the garment around the shoulders and allowing the ends to hang down in front of the body. Once again, the pallium was associated with dignity and formality, as well as being the appropriate narrow, rectangular design, all of which points to the epitrachelion finding its origins in the pallium. (In the West the name of the historic pallium eventually came to be associated with a badge of archepiscopal office, a fact which further underscores its revered position in garment history.) As the noted liturgical scholar Duchesne observes, “In the last analysis this scarf [the pallium] was, no doubt, a relic of the short mantle which had been brought into fashion in the Roman Empire by the Greeks. But the discolora pallia of the Theodosian Code were evidently scarves,

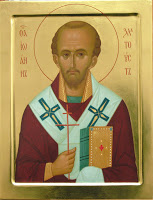

and scarves of office, which were worn over the paenula… .” In modern usage we are accustomed to seeing the epitrachelion held together with buttons up the front (or, more rarely, as a solid piece of fabric with a hole for the neck opening, sometimes referred to as the “Athonite” style due to its common use on the Holy Mountain), but this is a much later adaptation of the garment. The common form of the epitrachelion in early centuries was certainly that depicted in icons of the early Fathers, such as St John Chrysostom and St Basil the Great; in these depictions it is clear that the epitrachelion is a narrow, non-buttoned length of fabric hanging down from either side of the neck.

In addition to these artistic representations there are also a number of extant, embroidered epitrachelia, many dating from as far back as the eleventh century,that are made in this non-buttoned style as highly embellished, narrow rectangles to be draped around the neck, all of which support the origins of the epitrachelion being traced to the pallium. It is significant to note that, when laid out flat, an orarion and a buttonless epitrachelion without shaping at the neck are virtually identical, another argument for the common origin of both garments in the pallium.

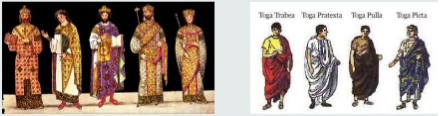

We now return to that garment which began our discussion of the various clerical scarves of office, the omophorion, the preeminent garment which identifies its wearer as a bishop. It is with the development of the omophorion that we find the most striking evidence of a conscious transference of symbolic garments from the civic to the spiritual realm. For in the omophorion of the Orthodox Church we find the last remnant of that great and quintessentially Roman garment, the toga. Other writers have opined that the origins of the omophorion are to be found in the pallium, but the widespread use of the pallium in late antiquity means that such a garment would not have been suitably commensurate with the status and respect accorded to bishops in the early Byzantine period. In order to better understand the elevated requirements of the bishop’s particular badge of office, it is necessary to consider the authority accorded to the Christianepiscopate as early as the Constantinian era:

We now return to that garment which began our discussion of the various clerical scarves of office, the omophorion, the preeminent garment which identifies its wearer as a bishop. It is with the development of the omophorion that we find the most striking evidence of a conscious transference of symbolic garments from the civic to the spiritual realm. For in the omophorion of the Orthodox Church we find the last remnant of that great and quintessentially Roman garment, the toga. Other writers have opined that the origins of the omophorion are to be found in the pallium, but the widespread use of the pallium in late antiquity means that such a garment would not have been suitably commensurate with the status and respect accorded to bishops in the early Byzantine period. In order to better understand the elevated requirements of the bishop’s particular badge of office, it is necessary to consider the authority accorded to the Christianepiscopate as early as the Constantinian era:Under conditions, Constantine gave to the bishops the power of arbitration in certain suits; their findings were to be valid in the courts of the Empire, and it was enacted that the decrees of the Christian synods were to be upheld. Honorius later on enlarges the legislation of Constantine and gives to the arbitration of a bishop an authority equal to that of the Praefectus Praetorio himself, an officer second in importance only to the emperor. It would be thus quite natural that a bishop being a high Roman official should adopt some of the ensigns of his civil duties.

This official honor and authority bestowed by the emperor upon the Church’s episcopate continued and expanded under Justinian:

Although the emperor appointed his bishops, the Justinian Code conceded to them independence, immunity, and authority to an extent that must have made themsovereign lords wherever the imperial power was not immediately present. In the administration of the Byzantine Empire the bishop occupied a position second to no one except the emperor himself. In the city the bishop nominated the municipal officers, maintained fortifications, aqueducts, bridges, storehouses, and public baths; supervised weights and measures; and controlled the city’s finances. In the provinces it was again the bishop who recommended candidates for the administrative posts and maintained a close watch on their activities, including those of the governor himself. In addition to these administrative powers, the bishop acted as judge. The age did not distinguish between the two sources, spiritual and political, of the bishop’s power.

Although the emperor appointed his bishops, the Justinian Code conceded to them independence, immunity, and authority to an extent that must have made themsovereign lords wherever the imperial power was not immediately present. In the administration of the Byzantine Empire the bishop occupied a position second to no one except the emperor himself. In the city the bishop nominated the municipal officers, maintained fortifications, aqueducts, bridges, storehouses, and public baths; supervised weights and measures; and controlled the city’s finances. In the provinces it was again the bishop who recommended candidates for the administrative posts and maintained a close watch on their activities, including those of the governor himself. In addition to these administrative powers, the bishop acted as judge. The age did not distinguish between the two sources, spiritual and political, of the bishop’s power. For someone with authority as great as that wielded by a bishop, no mere pallium, however dignified, would suffice; he must wear the greatest symbol of office the ancient world had devised: the toga. We must remember that by the second century AD the toga was no longer used in its old senatorial form as a full cloak to cover the body, but as a purely ceremonial garment with distinctive folds, the toga contabulata, as shown in the consular diptych of Consul Anastasius. In this diptych we see the consul wearing the toga, folded into a band approximately eight inches wide (this accorded with the eight-inch band of ornamentation along the edge of the toga), Y-shaped configuration as the present-day omophorion, with the exception that the back section of the garment is wrapped to the right front and draped over the left arm. (In modern usage, this section of the garment simply hangs down the back of the bishop and is not brought to the front of the body; this difference is most likely because bishops now usually wear the omophorion standing while all extant ivory consular diptychs show the consul seated.) This and other consular diptychs as well as iconographic depictions provide a very strong visual argument for the omophorion originating from the toga, not the pallium.

Further evidence is found in the Theodosian Code, where the pallium is bestowed upon lower-ranking officials, not those with the kind of overarching authority a bishop would wield. Yet again, we must look not only at the design of the garment, but also consider its appropriateness and suitability according to the mindset of the Byzantines. A garment which was seen as suitable to a consul in the secular realm would accord perfectly with the respect and honor due a bishop in the spiritual realm.

It is likely that the omophorion began as a garment denoting the bishop’s civil, rather than spiritual, authority. It is interesting to note that even in modern liturgical practice, the bishop wears the great omophorion until the reading of the Gospel at which point he removes the great omophorion and remains without omophorion until the end of the Great Entrance at which point he dons the small omophorion (an abbreviated omophorion of rather late development). This may well hark back to an early practice in which the bishop would have worn the omophorion until the Little Entrance (i.e. the start of the Divine Liturgy proper), at which point he would have removed it for the remainder of the Divine Liturgy, from that point forward being vested as a presbyter.

It is likely that the omophorion began as a garment denoting the bishop’s civil, rather than spiritual, authority. It is interesting to note that even in modern liturgical practice, the bishop wears the great omophorion until the reading of the Gospel at which point he removes the great omophorion and remains without omophorion until the end of the Great Entrance at which point he dons the small omophorion (an abbreviated omophorion of rather late development). This may well hark back to an early practice in which the bishop would have worn the omophorion until the Little Entrance (i.e. the start of the Divine Liturgy proper), at which point he would have removed it for the remainder of the Divine Liturgy, from that point forward being vested as a presbyter.