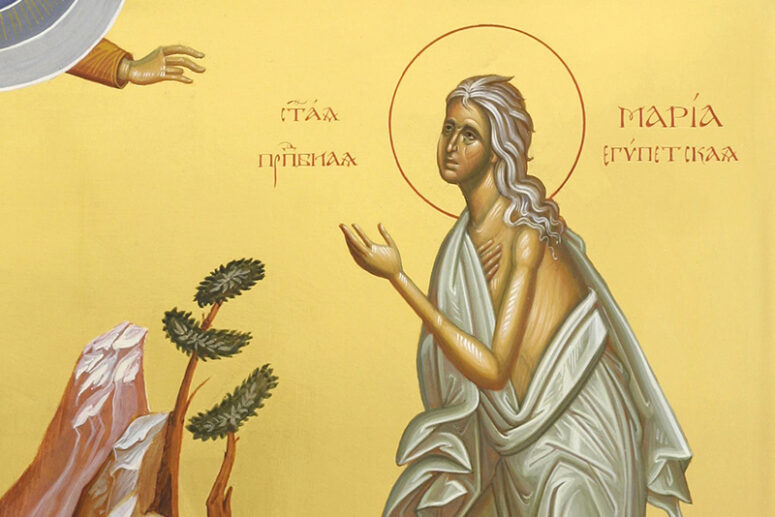

Two unusual features in the biography of Mary of Egypt have always puzzled me. First, how did a twelve-year-old girl who had given herself up to debauchery never once experienced pangs of conscience? The life of this future desert saint emphasizes her natural carelessness in fornication. Many characters like Dostoevsky’s Sonya Marmeladova, or Maupassant’s Boule de suif were drawn from life. Despite their “peculiar” lifestyle, they understood that they were drowning in mud and indulging in abominations. Mary of Egypt lived in Alexandria at the end of the fifth century. There were many Christian churches and shrines in Mary’s city, while some outstanding ascetics lived in the nearby desert. Nevertheless, Mary lived like a “child of the fields” in pagan antiquity, as if the Gospel had not been proclaimed to the world.

The second thing that amazes me is how Mary’s eyes suddenly opened, as the feeling of shame woke up in this deep-rooted harlot. Wherever this feeling may have come from, it is a miracle. Hearing this call to Christian service, the saint spent seventeen years in the wilderness to atone for seventeen years of sin.

These two questions are not merely of literary or theological interest to me. Every year, I meet more and more people who seem to be “morally insane” and sincerely do not understand what sin is. I do not know how to explain the concept of sin; in fact, I am not even sure if such an explanation exists. No one lectured Mary on morality or the observance of God’s commandments. Instead, the Lord did not let her into the church, and for some reason this “sacred resistance” suddenly opened Mary’s eyes.

Was Mary a “fallen woman”? In order to fall, one has to have a ground to stand on, but this girl grew up with sin. Did she have anywhere to fall from?

A fall is a technical term in the monastic vocabulary. It means a particularly serious sinful act. Most often in ascetic texts, this word describes a violation of the vow of chastity. A once standing person may suddenly fall. People walk on two legs. Animals move on four. A reptile crawls on its womb. Another meaning of the word “fall” can be found in the military lexicon. One can fall on the battlefield.

A Christian fights “against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places” (Eph. 6:12). Before the beginning of a monastic tonsure, the abbot throws scissors at the feet of the tonsured person. The future monk picks them up and resolutely puts them into the hands of the abbot. This is repeated three times. Then the abbot makes a “last warning” before performing the tonsure, “Look then to whom you are coming, with whom you are joining, and whom you are renouncing.”

To take tonsure is to challenge the devil, openly engaging in confrontation with him. Monastic tonsure is modeled after the sacrament of Baptism. Every Christian is a warrior of Christ, which means that he is at risk, under enemy fire and may be among the fallen.

A spiritual fall is not death yet, but it is a mortal wound. A person may still be alive after a fall, but sin is a “black hole”, draining one’s vitality. Sin can turn a living and cheerful person into a living dead.

There is no joy in sin. There is no life there. Only illusion and deceit. If a miracle suddenly happens and a fallen person begins to see clearly, the first thing he sees in the mirror is a dead man. At such moments, a person says to himself, “I am a corpse among corpses. I live out of habit, I move by inertia, but my life is long gone. I am not only a dead man; I am the one who inflicted mortal wounds on myself. When they were killing me, I helped my tormentors; I was on their side; I am the one who called them.”

Lamentations of a person wounded on the battlefield and still able to call for help constitute the content of the Great Canon by St Andrew of Crete. In the fifth week of Lent, this hymn of repentance is read in full. This most beautiful service begins in the morning, when the famous twenty-four penitential stichera by St Andrew of Crete are sung at the Presanctified Liturgy on Wednesday.

These stichera are very popular in monasteries. Connoisseurs of the church rubrics expect them every year. Twenty-four short prayers that end with the same chorus, “Save me before I utterly perish, O Lord!”

This is a cry for help, a call of a dying person, who says, “I am at death. I am on the edge. I am falling into an abyss. Lord, save me before I die.”

Similarly to St Mary, we go through several stages of repentance, from the “carelessness of debauchery”, which is always marked by blindness and insensitivity, to the “vision of one’s sin” and stillness before the image of the Blessed Virgin, an icon of purity and holiness.

The work of repentance is not limited by seeing one’s sin and thirsting for purity. There is a third step: readiness for redemption. The prudent thief, who defended Christ and received forgiveness and the promise of paradise from Him, was dying under the scorching sun, suffering from terrible torments. He accepted them as redemption and said, “…we are getting what we deserve for our deeds”.

Genuine repentance and awareness of one’s fall does not awaken despair, but readiness for work, preparedness for a new redemptive battle.

Venerable John Climacus wrote down very important words, “A sign of diligent repentance is considering oneself worthy of all the visible and invisible sorrows that happen to a person, and even more” (5:38).

For seventeen years of debauchery, St Mary paid with seventeen years of life in the wilderness. “I am getting what I deserve for my deeds.” This work is not for God. The Lord forgives us immediately, no matter how much we fall. We need this work of redemption. Not all of us are ready for asceticism. We often lack strength and determination to pursue it. St John Climacus speaks of readiness for the meek and grateful acceptance of sorrows and illnesses in order to atone for one’s falls. The Lord entrusts us with the work of self-purification. This is the meaning of sorrows.

However, there is more to repentance than readiness for redemption. The most important thing that the penitential canon teaches us is mercy for the fallen, and consequently for ourselves.

A person, who truly repents, is distinguished by kindness, mercy and forgiving attitude. A repentant person is someone who has survived the fall and the uprising. He knows the breath of death when the last drops of life are nearly gone. Such a person can sympathize with other people’s falls. Who knows, perhaps the Lord sometimes allows our falls so that we become kinder and more forgiving?

Translated by The Catalogue of Good Deeds

Source: https://www.pravmir.ru/arhimandrit-savva-mazhuko-mariino-stoyanie-put-ot-rasputstva-k-svyatosti/?fbclid=IwAR0jZc0DY_cC_xoxBimkspIHN43WDVbiqc3C5urIOQYKsuwqY0_df1rimK