In Europe, it took until 1445 for Johann Gutenberg to invent his printing press. Before that, all the books had to be copied by hand. It was a painstaking process, and mistakes – some intentional others not – were inevitable. Sometimes, the scribes made changes to the text on purpose. The Holy Scripture was the most common written text at the time, and so were the mistakes in copying it. Many of the mistakes reviewed below have remained in some of the most widely used biblical translations.

The difficult work of a scribe

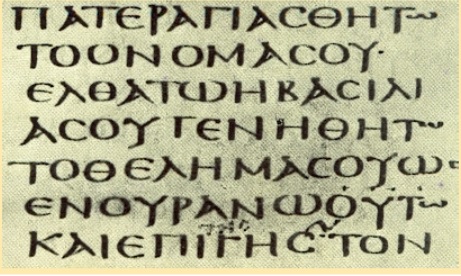

Europe did not know paper until the 11th and 12th centuries. Before that, scribes were writing on calf skin or papyrus. Both materials were expensive, and every scribe sought to make the most use of the available writing space. Some common techniques were avoiding spaces between words or minimising the size of the letters. Many used no commas or full stops and resorted to acronyms and abbreviations. Generally, the older the manuscripts, the more economical the scribes tended to be with their writing space. Yet this manner of writing complicated the task of copying the text in later years.

To copy the text, scribes would either put the original in front of them or have someone dictate the text to them. Both options led to errors, intentional or not.

Unintentional errors

While copying from the written texts, scribes would often omit letters or whole words, spell words incorrectly or get their grammar or syntax wrong. Many factors were at play. Fatigue, original text quality, professionalism and literacy of the scribe all influenced the outcome of the work. Scribes were highly paid, and some would rush their projects to get their pay and take new orders.

When scribes were too economical or had poor handwriting, mistakes in copying their texts were almost inevitable.

Frequently, errors were made when scribes misread the abbreviations in the text. In the first book of Corinthians (12: 13), we read, “For we were all baptized by one Spirit.” Yet some Greek manuscripts read, “For we all drank the same liquid.” The scribe had understood the abbreviation PMA, which commonly stands for PNEUMA (Spirit) to mean от POMA (liquid).

Where two adjacent lines ended in the same word, scribes could mistakenly omit one of them. In the Vatican Codex, John 17: 15 “My prayer is not that you take them out of the world” was copied as “My prayer is not that you remove them from evil”. Sometimes, the negligence of the scribe reversed the meaning of a passage entirely. For example, the line from Acts 19: 34 of the Vatican Codex, reading, “they all shouted in unison for about two hours: “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!” was repeated twice.

When the original was dictated, the quality of the writing was affected by the condition of both reader and scribe. Some errors resulted from mishearing or misreading. Homophones (words sounding the same but spelt differently, like grate and great) are a case in point.

The pronunciation of some Greek works changed considerably over time. For example, the letters η, ι, υ, ει, οι, υι, pronounced as diphthongs in the times of Christ, later came to be read as “ee”. This created a large number of homophones, complicating the correct understanding of spoken Greek.

Intentional changes

Intentional changes were made through pride, piety or misunderstanding, especially when copying similar fragments of text.

One example of the former is the use of a more formal word instead of the more common one, like “bed” instead of “straw rug”. Some fragments of the Scripture -especially those that the Jews wrote in Greek – were replete with solecisms, or grammatically incorrect phrases that still retain the original meaning (e.g. “He can’t hardly walk”, “Whom shall I say is calling?”). Some scribes chose to alter the text in these cases to correct the errors.

The next type of intentional change occurred when a scribe added a title or epithet at the mention of the name of the Lord or an apostle. For example, in Galatians 6:17, “the marks of Jesus” later scribes wrote “the marks of our Lord Jesus”, or “the marks of our Lord Jesus Christ”.

Lastly, some mistakes were a product of misunderstanding or pride. For example, the short text of the prayer “Lord our Father” from Luke 11:2-4 was replaced by the longer version from Matthew 6: 9-13. The line from Matthew 9:13 “For I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners” was supplemented with the insertion “to repentance”, same as in Luke 5:32. “Scribe” was automatically equated with “pharisee”, and the word “visibly” was almost always added to the phrase “Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you.” (Matthew 6: 6)

Conclusion

Despite all the errors reviewed above, the Bible is still the most accurate of all ancient texts. The differences observed in the different manuscripts are still small and bring little distortion to Biblical teachings. The known manuscripts of the Old and New Testaments number in the thousands, and it presents relatively little difficulty to compare the diversions and track down the original text.