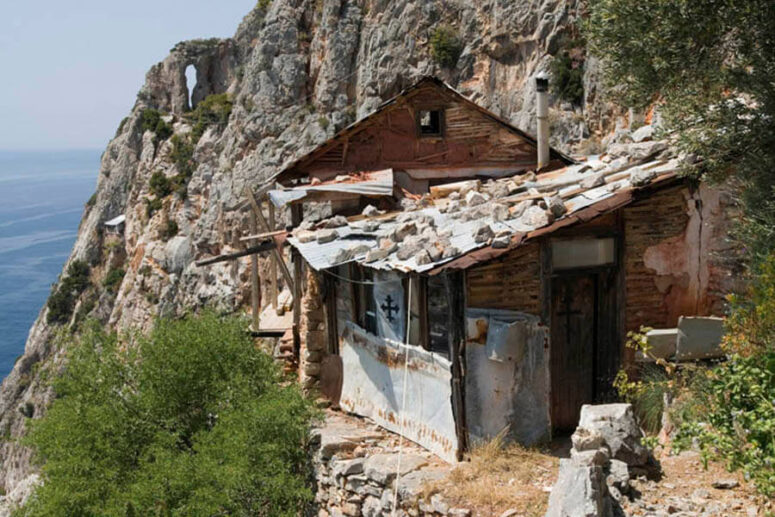

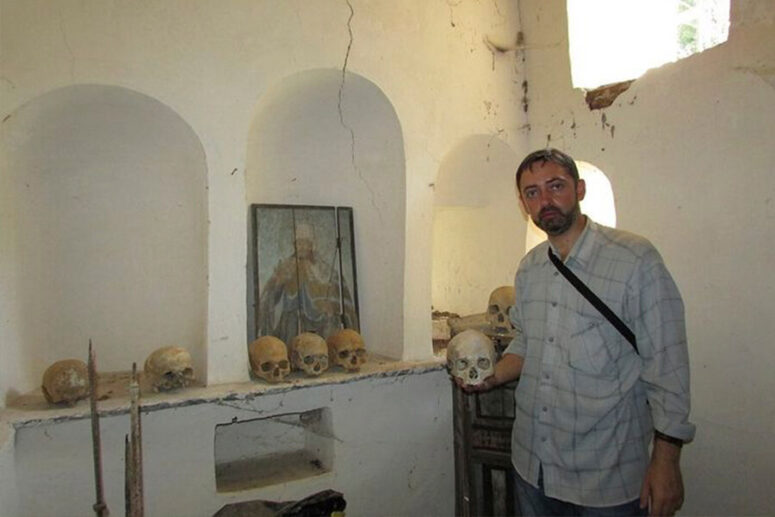

On Mount Athos, reminders of death are ubiquitous, yet their perception is unusual. There have been no births here for over a millennium, yet many people come here to die or prepare for their departure. The Holy Mountain is like a giant memorial garden, the only one of its kind. In cells, houses, caves and churches, one comes across the relics of the saints, and most sites and buildings keep the bones of their former dwellers. The yellow, wax-like colour of the bones speaks to the righteous life of the deceased, known or unknown. Monks carry the bones along with them in small bags, medallions or boxes, as a sign of their spiritual connectedness and love for the departed. A traveller can come across some bones stacked up in an orderly pile, sometimes covered by a cobweb, wrapped in a rag or hidden in a plastic bag suspended under a roof. They serve as lasting reminders of the occupants of these dwellings. Looking at them, one does not feel any sadness. Instead, one has a sense of joy and reassurance that the place is not abandoned.

The reminders of death are ever-present, yet its ubiquitous visibility makes it seem virtually non-existent.

On Mount Athos, there is no fear of death, an attitude that is firmly grounded in Christ’s teachings on man and his place in the world. A follower of Christ is always on a journey that takes us beyond our life on earth. Without this sense of purpose and perspective, our lives have little worth. By making our earthly life a goal in itself we bring upon ourselves the terror of our “second death”, the death of our spirit with no hope of salvation. For a Christian – and especially for a monastic, – achieving everlasting life means dying for the world, once and for all: “Very truly I tell you, unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds. Anyone who loves their life will lose it, while anyone who hates their life in this world will keep it for eternal life.” (John 12: 24, 25)

Dying for the world is the main preoccupation of any settler on the Holy Mountain. Everyone is hard at work to extinguish their passions and lay to rest their futile desires and idle dreams. We trample over death by death alone.

Mindful that Hades has no power over the resurrection, a dweller of Mount Athos also take guidance from this maxim from the writings of Hieromonk Sophronius (Sakharov): “Keep your mind in hell, and fear not.”

The bones in the windows of Mount Athos’ chapels are evidence of victory over death and the absence of fear; it shows that the genuine achievements of one’s life will not perish, but will stay beyond one’s time on earth like a priceless pearl in the hands of a wise merchant. A dweller of the Holy Mount will also find encouragement in these words, “Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting?” (1 Corinthians 15: They will mean a lot to them because they talk about the resurrection. By descending into hell and putting death in shackles, Christ the God-Man empowered every Christian to follow Him and to resurrect for everlasting life in God, despite dying at a distance from Him.

A good death is also a resurrection, and so preparing oneself for one’s departure is a large part of one’s monastic calling. The monastics of the Holy Mountain are always mindful of their departure.

Their ability to defeat death and meet the moment of their departure with calm, peace and with inner joy is the surest sign of their accomplishment as Christians.

Translated by The Catalogue of Good Deeds

Source: Rak Pavle. Approaches to Mount Athos Satis Publishers, 1995

https://obitel-minsk.ru/chitat/den-za-dnyom/2021/gora-afon-10-08