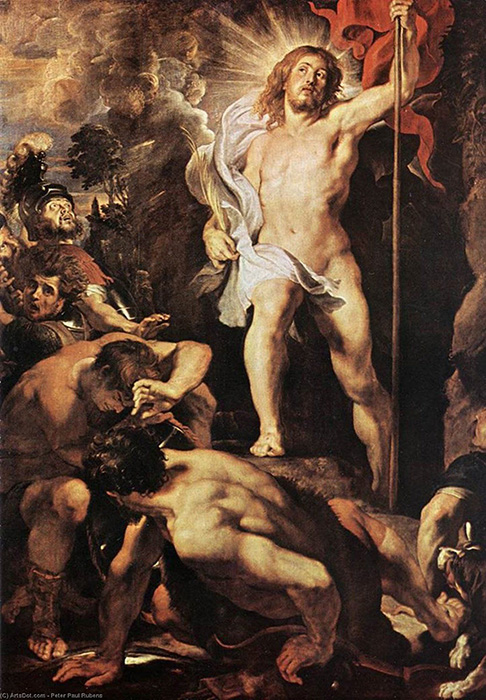

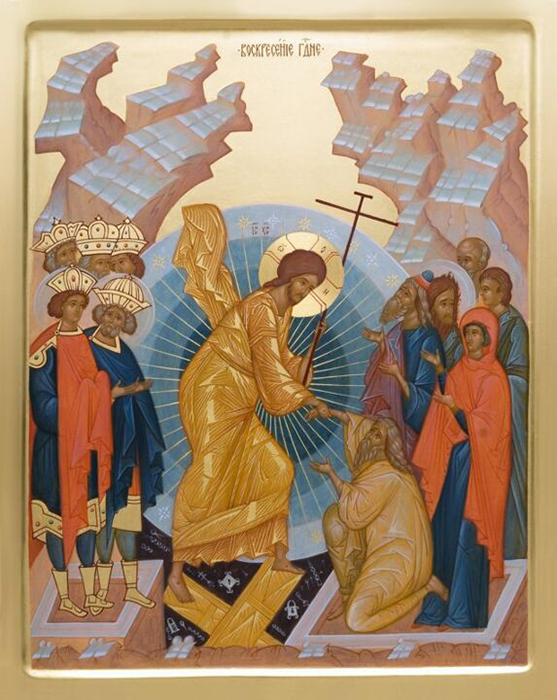

In many Orthodox depictions of the Resurrection of our Lord, Christ is shown holding a banner. This way of showing Him has become so common that it rarely raises any questions. We see Christ holding a banner in many Paschal e-cards. Depictions of Christ with a banner also occur on the front walls of many known churches across Russia, including Saint Isaac’s Cathedral in Saint Petersburg, and the Church of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, both built in the 19th century.

In verbal descriptions, the object in Christ’s hands is sometimes called ‘gonfalon’ with an icon on its cloth. This begs the question: what holy image could Christ be holding above him? Frequently, the banner shows the image of the cross. But how did the banner come to replace the cross? The use of terminology is another source of uncertainty. For example, the banner is sometimes called the labarum or oriflamme, but both terms relate to different cultures and historical periods. These unanswered questions challenge our understanding of the meaning of the banner.

So let us find out about the origins of the tradition to depict Christ with a banner and its symbolic meaning.

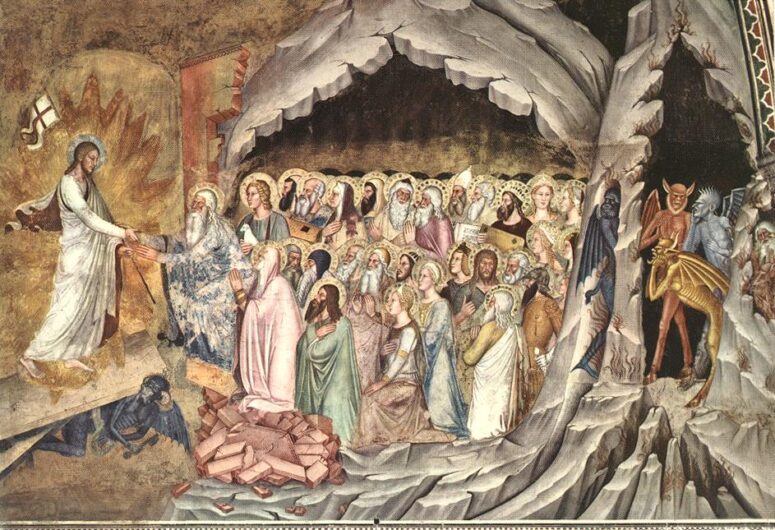

Old images of Christ’s resurrection

The traditional depiction of the resurrection (the Anastasis, in Greek) evolved in the first centuries AD and was fully established by the sixth century. Up until the 11th century, the icons of the resurrection showed Christ holding the cross, a scroll, or the Gospel. There was no tradition of depicting a banner in the Saviour’s hands as a symbol of His victory over death and Hades. Compositionally, the images resembled depictions of Christ’s descent into Hades to liberate the souls of the righteous and sinners.

The first depiction of Christ with a banner

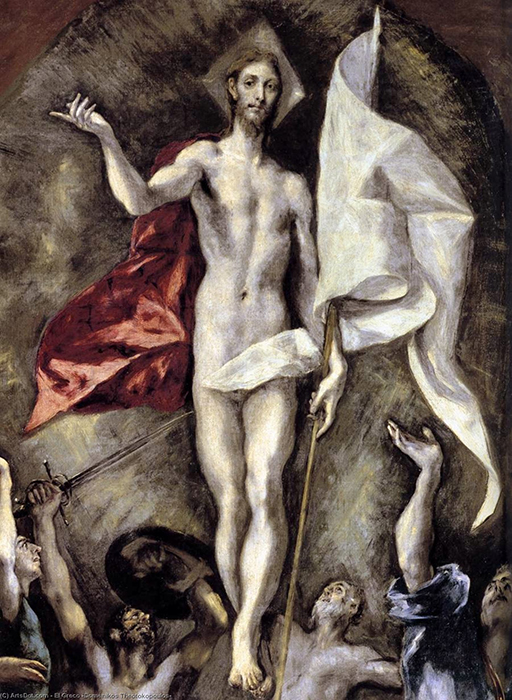

In the 11th century, new narratives begin to be introduced in the tradition of Western Christianity, including Christ’s descent into Hades and His rising from the tomb.

The depictions of Christ rising from the Tomb narrated the events of the Resurrection from a worldly, or factual, perspective. In Orthodox theology, their reception was controversial. Many are still sceptical of the possibility to convey the spiritual reality of Christ’s rising from the dead within the tradition of realistic art.

The first depictions of Christ with a banner in hand occur in the visual narratives of His descent to Hades. They relate to a tenet of the Apostles’ Creed, which is not present in the Nicene Creed, and therefore they have not been typical in the Orthodox iconographic tradition.

One of the earliest representations of the descent to Hades can be found in the miniature edition of Tiberius’ Psalter. Admittedly, the artist places the banner above Jesus’ halo. Jesus Himself is shown extending his hands to the people in the harrowing of hell. The banner takes the form of a segment of a circle with straight lines – appearing like rays – extending from it.

One of the first depictions of Christ holding a banner is the illustration from St. Alban’s Psalter (1145), which shows Christ bending towards the harrowing of hell extending his right hand towards the people and holds the cross with a blue flag in his right.

Oscar Loerke suggested that the banner on the depiction was a motif from the hymn of the Latin poet and hymnographer Venantius Fortunatus, glorified by the Western Church in the sixth century. However, this does not explain why it took so many centuries for this detail to be adopted by the iconographers.

Interestingly, showing Christ with a banner in His hands was common among the architects of England and France, while this detail is missing from the early depictions of Christ in Italy and Spain. Due to this fact, the banner may justifiably be referred to as the French Oriflamme. It took European artists until the 14th century to make this detail a part of the common depiction of Christ descending into Hades.

Interpretation and symbolic meaning

Traditionally, the banner in the hands of Christ is interpreted as a symbol of victory. However, it meets with disbelief and scepticism among some Orthodox who object that the resurrected Christ already represents His defeat over Hades and death.

Orthodox art scholar Svetlana Ivanova writes, “The Oriflamme is less about victory, and more about mobilisation for an assault, a call for the warriors to come together. The oriflamme was not a military insignia, but more a sacred sign that inspired. It was displayed before the troops only in the war against the enemies of Christianity or the kingdom, and only if the King was the commander of the expedition. Only the King could display the oriflamme, and to the rest, it was the indication that the King was himself fighting in the war and was in command. According to Ivanova, the use of this symbol in the depiction of Christ’s descent into Hades sends the following message: “Christ is depicted as he is waging a war against the enemy of all men and His Heavenly Kingdom. He is fighting against Satan. It is not a representation of His victory, but only of the beginning of His decisive battle against the army of Hades, and He is going it alone, bearing the banner of a monarch. Eventually, the banner appeared in the depiction of Christ’s rising from the tomb, and both narrations become elements of the narration of the holy war with the kingdom of the devil and death and the beginning of the main battle under the holy banner and of His victorious return.

The cross on the cloth or handle should be seen as the equivalent of the cross.

Depiction of the banner in the icon of the resurrection of Christ

At some stage in Western art, the iconographic depictions of Christ’s descent into Hades and rising from the tomb become mixed. As a result, Christ begins to be shown holding the flag in all narratives about His resurrection.

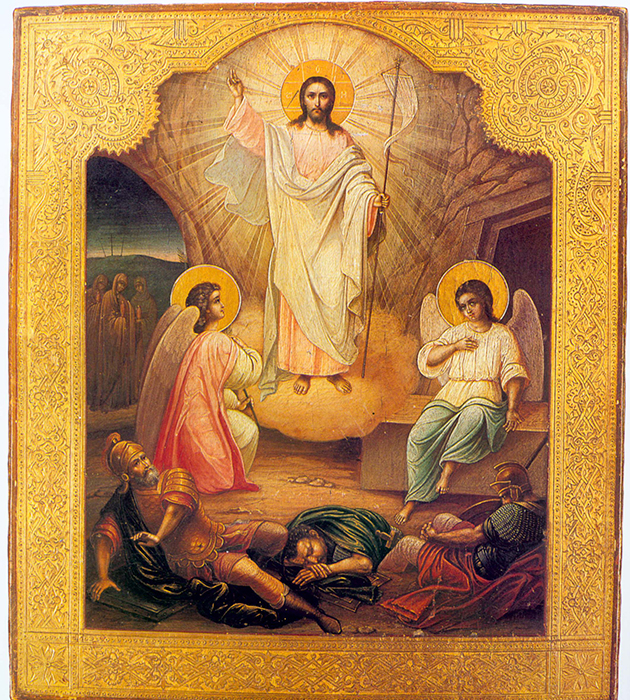

In approximately the 17th century, the tradition to depict Christ with a banner was adopted in Russian Orthodox iconography and church architecture.

This review of the history and symbolism of the banner in the iconographic depictions of Christ may lead us to the following conclusions. This detail appeared on the icons of the resurrection through the influence of Western Christianity and art. The interpretation of the Oriflamme and the account of its historical symbolism do not contradict the doctrine of Orthodox Christianity. However, the use of the banner does not seem to have deep roots in Eastern Orthodox tradition or the writings of the Holy Fathers. As a result, the symbol of the banner is rarely used in modern Orthodox iconography of the Feast of Resurrection, where the Saviour is shown empty-handed or holding a cross. Presumably, the Russian icon painting tradition has returned to the original ways of depicting Christ.

* Oriflamme was the battle standard of the King of France in the Middle Ages. The banner was red or orange-red silk and flown from a gilded lance.

Source used: https://bogoslov.ru/article/1655238