Genesis 28:10-17 describes a vision which Jacob had in a dream at the place that became known as Bethel (v. 19). Throughout the patriarchal narratives in Genesis 12-50, altars are set up by the patriarchs at various places, not coincidentally at 12 sites within the later territory of the 12 tribes of Israel. These narratives regarding the patriarchs represent the collected traditions of the 12 tribes regarding their forefathers. Bethel would be a cultic site for centuries, notably one of the two sites of Jeroboam’s apostate religion in the Northern Kingdom. The legacy of Jacob’s dream, however, in Second Temple Judaism and Christianity was untethered from the place where it occurred, and refocused upon the symbolism of the vision itself. Much of the discussion of this vision has centered around Jacob’s “ladder,” though its translation as “ladder” has somewhat obscured the original reference of Jacob’s dream.

In Jacob’s dream he sees what is called in Hebrew a “sullam” whose base is upon the earth and which reaches to the heavens. Angelic beings are ascending and descending upon the “sullam.” He looks to its peak and sees Yahweh standing atop it, who reiterates to Jacob the promises made to his grandfather Abraham. Due to the dream, Jacob concludes that the place in which he had been resting is “the house of God” and “the gate of heaven.” The anointing of sacred stones, as performed by Jacob in v. 18 was a common West Semitic religious ritual and dedicatory rite. Jacob not only makes this a sacred ritual site, but he changes the name of the place from Luz to Bethel (v. 19).

The question then turns to what precisely a “sullam” is. This is complicated by the fact that this word is used only here in the entirety of the Hebrew scriptures. A word which occurs only once in the scriptures is referred to as a hapax legomena. There are many such words in both the Old and New Testaments. In the New Testament, such Greek words often have ample use in extra-Biblical Greek literature to determine the word’s general usage and meaning. In the Old Testament, there is in most cases little or not literature to compare. Information then has to come from other related Hebrew words, related words in other Semitic languages of the period, and words used in ancient translations. “Sullam” is a noun derived from the verb “salal” which means “to pile up” or, when referring to a road, “to pave.” Another noun derived from this verb, “mesilla” is used repeatedly in the Old Testament to refer to a paved road. The plural of this noun is used in 2 Chronicles 9:11 to refer to a wooden element of the temple’s construction. Though its exact referent is unclear, both the Greek and Latin translations of the plural here identify it as a staircase. Another related noun “solala” is used to refer to a siege ramp of the kind constructed alongside a city wall. Interestingly, the Akkadian word “simmiltu” refers to a connection between the heavens and the netherworld through which messages can be sent. Ugaritic texts use related words to describe places and beings associated with a gateway or other connection between these places. In the Greek Old Testament tradition, “sullam” is translated by “climax,” a word which we have become used, in English, to translating as “ladder.” In Greek, however, this word can refer to either a ladder or a staircase. Other uses of “climax” in the Greek Old Testament tradition tend strongly toward its interpretation as a stairway. In 1 Maccabees 5:30, “climax” unambiguously refers to a ladder. However, in every other usage, it very clearly refers to a staircase (Neh 3:15; 12:37; 1 Macc 11:59).

The imagery of a connection between earth and heaven as well as that of a staircase is united in the context of a ziggurat. The image that accompanies this post is a photo of the remains of the great ziggurat of Ur, the original home of Jacob’s grandfather Abram. These temple complexes in Mesopotamia were man-made recreations of the mountain of God which would allow kings in particular to ascend to the dwelling of the gods in order to interact with his fellows. The ziggurat imagery is also the subject of the story of the tower of Babel earlier in Genesis. It is also in keeping with Jacob’s identification of the place as not only the gate of heaven, but also the “house” of God. The Hebrew word “bayith,” transliterated in English as “beth,” when used in reference to a deity, means “temple.” Jacob’s vision, then, is of Yahweh standing atop his temple mountain, with his angelic servants ascending and descending a staircase or ramp leading from his dwelling place to the earth and back.

While Jacob’s vision is not directly referenced in the Old Testament, it fits within a prominent motif within the Hebrew scriptures of the ascent of the mountain of God. Possibly the most prominent example of this motif is Moses’ ascent of Mt. Sinai to the dwelling place of Yahweh in his divine council. This ascent to the vision of God is applied to the spiritual life famously by St. Gregory of Nyssa in his Life of Moses. Another example from the Hebrew scriptures would be the Song of Ascent, comprised of Psalms 119-133, typically sung during pilgrimage to the temple atop Mt. Zion. Other Psalms, such as 15 and 24 likewise describe the life of the faithful as ascending the mountain of God. These latter two Psalms, however, phrase the issue as a question, “Who can ascend the mountain of God?” Moses made his ascent of Sinai while the rest of the people were prohibited from even so much as touching its base. What ultimately enables human ascent to God’s presence is the descent of Yahweh from the heights of Paradise.

In John 3:13, Christ states that no one has ever gone into heaven but the one who came from heaven, the Son of Man. This imagery is allied with that of John 1:51, in which Christ says to Nathanael, “Truly, truly I say to you: After this, you will see heaven open and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of Man.” Here, Christ himself is the “sullam” of Jacob’s vision, not a ladder, but a temple. Christ is himself the dwelling place of God with man. He is himself the means by which humanity comes to know the Father. Earth and heaven are connected and brought together in his flesh. The language of Jacob’s dream is also frequently applied in the hymns and prayers of the Orthodox Church to Christ’s mother, the Theotokos. This is primarily with reference to Jacob’s identification of the place in which he slept upon awaking. The womb of the Theotokos is both the place in which God dwelt after her virginal conception and the gate through which Christ passed on his way from heaven to earth. Jacob’s dream vision can therefore ultimately be seen to be a vision of the incarnation.

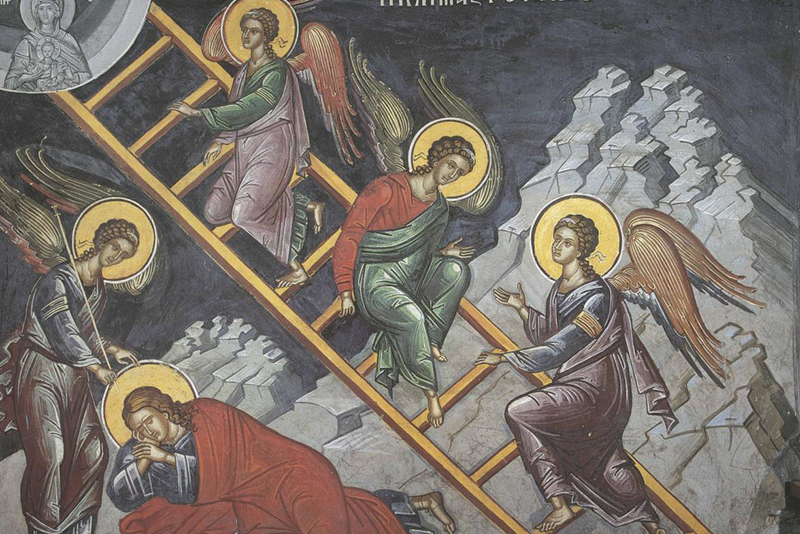

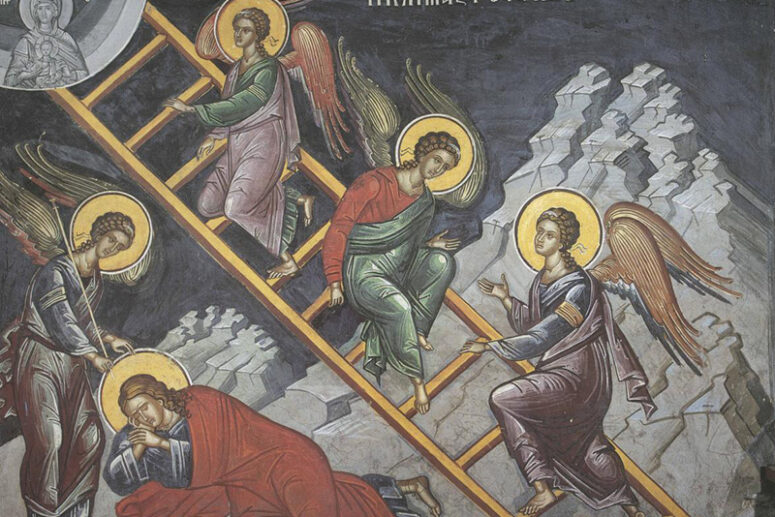

The imagery of Jacob’s vision, however, is perhaps most prominent in the text of St. John Climacus’ Ladder of Divine Ascent. This text and the accompanying iconography clearly understand the means of ascent as a ladder. Christ’s descent and his status as the temple staircase allow for, and are the means of, humanity’s ascent to God. The depiction of a ladder is not incorrect or unhelpful per se, as long as it does not serve to separate this imagery from the larger motifs and themes of the mountain of God and its ascent. St. John of the Ladder is also St. John of Sinai. Meditation upon Jacob’s vision serves as a reminder of the goal and purpose of human life. It also speaks to us of the incarnation of Christ, which makes true human life possible. The moment of God’s revelation of himself to Jacob leads us, as it does in John 3:13-15, to the full revelation of God to us, in the cross of our Lord and God and Savior Jesus Christ.

Source: https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/wholecounsel/2019/04/01/jacobs-ziggurat/