Representing Two Mutually Reinforcing Spiritual Trends in Monasticism

The history of the Russian Church often escapes the attention of most Orthodox people. Typically, our knowledge of it is limited by a few facts from the Synodal period and some information (thanks to the memory of the new martyrs) from the twentieth century.

If a person becomes interested in the history of the church, his attention is primarily attracted by the first centuries, the era of the Ecumenical Councils, and then perhaps the Mid-Middle Ages, with the Great Schism of 1054, etc. It does not always come to the history of Christianity in Russia. This time I would like to draw attention to this gap in our knowledge of church history, due to the memory of St Nilus of Sora (Nil Sorsky).

The name of this ascetic is associated with the famous dispute between the so-called possessors and non-possessors, in many aspects determining the further vector of the historical development of the church and its relations with the Russian state. Historians are still debating about some of the related events and their meaning. Perhaps this dispute might awaken interest in the history of our church among those interested in studying the details for themselves.

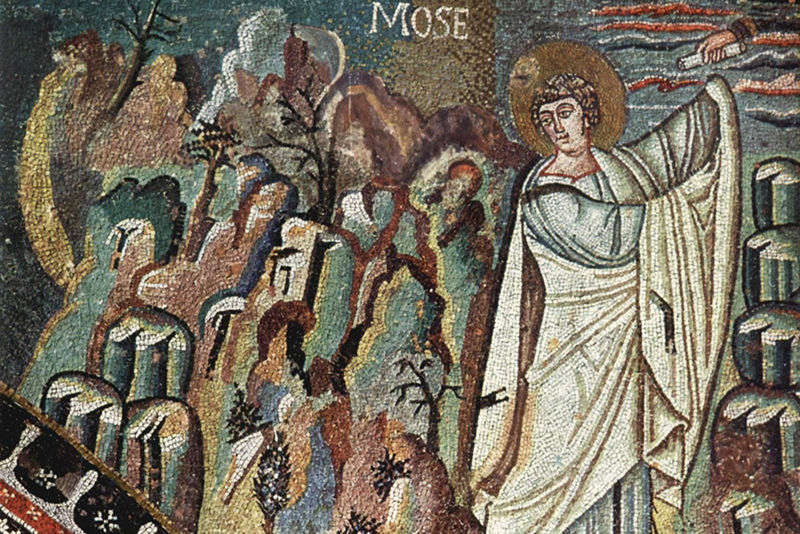

To begin with, let us venerate the memory of St Nilus and say a few words about him. He lived in the 15th and early 16th centuries. By origin, he was a descendant of the boyar family of the Maikovs. He was tonsured at the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery, but regarding its rules as too casual, he set off on a journey in order to search for the highest monastic perfection. He was greatly influenced by the lifestyle of the Athonite monks, from whom he adopted the rules of contemplative prayer. Returning to his homeland, St Nilus settled on the Sora River, a part of the Volga basin (present-day Kostroma region), where he set up a cell and a small wooden chapel for himself. Due to his exceptionally strict rules of life, the number of followers that eventually settled next to St Nilus never exceeded 12. It is very important to note that venerable Nilus paid almost no attention to organizing the life of his community, which, despite his general spiritual guidance, was rather a residence of hermits (possibly a skete) than a monastery. St Nilus renounced the possession of any property, relying exclusively on the ascetics’ own efforts in producing food and agreeing to take alms only in cases of the most extreme need. Leaving the skete was generally prohibited.

Following the tradition of the Belozersky Monastery, introduced by St Cyril, the venerable prohibited any land ownership. Being a strict ascetic, a contemplator, and a connoisseur of the inner life of a person, St Nilus did not lay that much emphasis on the rules of community life, as they were mostly regulating the outward discipline. Together with his followers, who were called the Trans-Volga elders, he sought to develop the very essence of asceticism and formed the “party” of non-possessors.

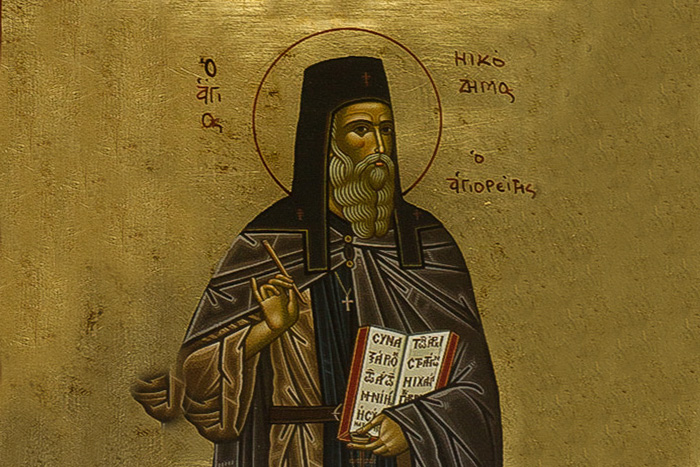

Their opponents were led by another saint, St Joseph Volotsky. In a nutshell, the essence of the conflict consisted in the possibility or impossibility for monasteries to own land, peasants and villages assigned to them. This dispute was raised at the Moscow Council of 1503, which took the side of the “possessors”. The authority of St Joseph was greatly strengthened by the successful struggle against the heresy of the “Judaizers”, as well as by the support of the princely power. Although there are some legends about this conflict, it should be noted that there is not a single documented evidence of any open antagonism, hostility or insults between St Nilus and St Joseph.

As already noted, St Nilus was a bearer of the Byzantine hesychast tradition. Venerable Joseph was more on the practical side and advocated the right of monasteries to own estates from the best of motives. He believed that it was possible to combine the wealth of a monastery with the personal poverty of its inhabitants. At the same time, the monastery thus had ample opportunities for charity. For example, in the years of famine the Dormition monastery, not far from the city of Volokolamsk, which was headed by St Joseph, fed up to seven thousand peasants, not counting the children. To incur such high expenses, the monks had to sell clothes and livestock and even got into debt. An orphanage was also built there for street children. Naturally, no such charity could be done by the followers of St Nilus whose whole life was focused on prayer, study of the Holy Scriptures and silence. They did not even have a joint meal, and lived in wretched cells.

It is necessary to mention some extremes of each of the parties. For example, in the monastery led by St Joseph, the prayer was put on a kind of a “production line”, and the requests of those who did not contribute the required amount (albeit through misunderstanding as it was the case with Princess Maria Golenina) were left unfulfilled. The “possessors” also defended the priority of the princely power in both state and ecclesiastical matters, which largely convinced Prince Ivan III to take their side. The extremes of non-possessors were manifested in the fact that they refused even alms. Venerable Nilus believed that monks need spiritual charity in the form of a word rather than bodily charity. They also underestimated the significance of the Holy Tradition and treated heretics more leniently. Although the views of the non-possessors appear morally attractive, if taken to an extreme, they threatened normal relations between the church and the state of that particular time.

As a result, St Joseph Volotsky was glorified thanks to his victory and the state support, whereas St Nilus of Sora was canonized because of the popular veneration. It must be said that the conflict was not resolved by the Council of 1503, and stretched out for another half century, until the Stoglavy Synod of 1551. However, that is a slightly different story, with other characters.

The examples of St Nilus and St. Joseph represent the two different spiritual directions in monasticism, complementing one another. Everyone chooses their own path. In conclusion, I will say something that I always say in such cases. Thanks to the controversy that has arisen, we see that holiness is not a certainty, but requires much work. Even the saints were not devoid of certain flaws and vices, but they actively fought with them and with their virtues left us the hope that if they succeeded in reaching the kingdom of Heaven, then we will also find our way to it.

Translated by The Catalogue of Good Deeds

Source: https://pravlife.org/ru/content/prp-nil-sorskiy-i-spor-ob-imushchestvennyh-pravah-monastyrey