Menorah (Hebrew מְנוֹרָה lit. lamp) is a golden lamp of seven candlesticks, which was kept in the Tabernacle, and then in Solomon’s Temple until its destruction. This fundamental Jewish shrine, in somewhat modified form, also occupies an important place in every Orthodox altar. Why is this liturgical object so important that no altar can do without it? What is its purpose and symbolism? Why does the Orthodox Church consider the menorah an indispensable attribute of Christian worship?

Menorah as a symbol of the Universal Creation

The first attempt to explain the significance of the menorah was made by Philo of Alexandria, a Hellenistic theologian and apologist for Judaism. In his interpretation of the book of Exodus, Philo connects the structure of the menorah with the structure of the universe, where the central position is occupied by the sun (the central branch of the lamp). The branches of the menorah symbolize the planets of the solar system. In further works, Philo enriches that symbolism, emphasizing also that the central branch of the menorah symbolizes the feminine principle in the person of the progenitor Sarah (possibly due to the fact that the menorah is a feminine noun). Josephus Flavius continues that tradition and carries on with the cosmic interpretation of the menorah as a system of planets (Antiquities of the Jews, 3.146). Perhaps, that interpretation intends to emphasize the functionality and practical meaning of the celestial bodies as opposed to their deification by the pagans. Planets and stars appear here as created by God in order “to give light upon the earth” (see Gen. 1: 15-18) and be a means of distinguishing between seasons and years (i.e. be part of a man-made calendar system). Thus the lamp, placed in the Temple to the One God, showed the superiority of the God of Israel as the Creator of the Universe over all other “gods”.

Menorah and the world tree

Some scholars of the 20th century note that the branched form of the menorah may be associated with the ancient religious motif of the world tree appearing in many religions and myths (Hachlili, 2001, p. 36). The world tree, according to these ideas, is the axis of being. It permeates and connects the underworld (the roots of the tree), the earthly world (trunk) and heaven (branches). In the Judaic Tradition, that image was represented by the Tree of Life, planted by God in the midst of Eden, whose fruit gave immortality (see Genesis 2: 9). According to the researchers of Judaism, both the rabbinic and Christian traditions see the menorah as a symbol of God, since the Tree in the biblical context meant His presence. A curious detail here is the connection between the menorah and the almond tree, considered in Bethel a sacred tree, whose fruit symbolizes life. That connection is confirmed by the fact that the shape of the almond flower was part of the menorah’s decoration (see Ex. 25: 31-40). It is known that the rod of Aaron blossomed with almonds and was therefore kept in the Holy of Holies. Those images could not slip the attention of the Christian Church, which considered itself the New Israel.

Menorah as an archetype of the Cross and the Spirit

In the images of the world tree, the Eden’s Tree of Life and the blossoming Aaron’s rod through the eye of faith the ancient Christians saw the Holy Cross of the Lord. It is the Cross that restores access to the Tree of Life and its saving fruit of immortality, i.e. to the Holy Eucharist. The Revelation of John the Theologian describes the vision of the Son of Man, standing in the midst of seven golden lamps, i.e. the seven-branched candlestick (Rev. 1:12). The seven-branched candlestick personified the seven churches of Asia or the entire fullness of the church as the Body of Christ. In the Orthodox teaching, the church is created and nourished by the Sacraments, the number of which providentially coincides with the number of lamps on the menorah. It is no surprise, therefore, that Christian theologians began to regard the seven-branched candlestick as a symbol of the Holy Spirit, by which all church sacraments are performed, and through which Christ governs and presides in His Church.

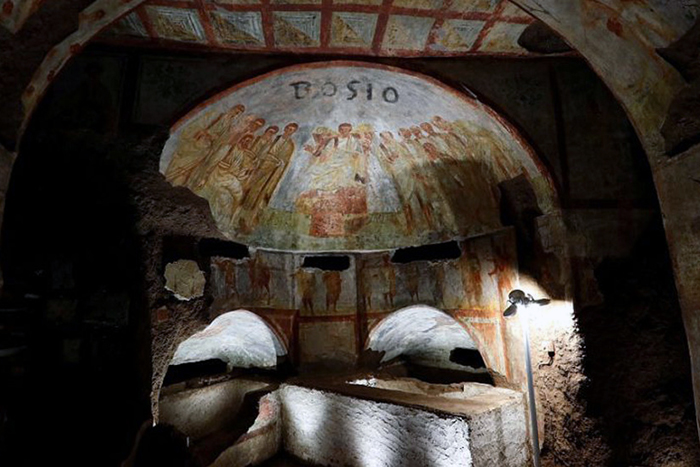

For a long time Christians used images of the menorah in parallel with the Cross (mosaics with a menorah in Sts Cosmas and Damian church in Rome (the 6th century), numerous illustrations in canon laws), considering it a symbol of the Messiah. The Byzantine writer Procopius of Caesarea writes that the Byzantines, during the wars with the Vandals, allegedly conquered the last menorah from the Temple of Solomon (History of Wars, IV, 6-9). Subsequently, it was kept in Constantinople until the city was taken by the crusaders.

That explains the obligatory presence of the menorah in Orthodox altars. The church not only shows its succession in relation to the Temple of Solomon, but also stresses the fact that all the Sacraments are performed in the Spirit before the Face of God Himself. It is no coincidence that the menorah is located between the altar stone on which the greatest Sacrament of the Eucharist is celebrated and the Upper throne, the place where the bishop, i.e. the chief priest in the community sits. That also shows us the connecting and central role of the Holy Spirit, which alone can fill with grace the ministry of the church’s hierarchy, breath life into the Old Testament symbols, animate our church mysteries and sacraments and turn our altars into places of the Messiah’s Presence.

Would it be appropriate to place a seven branch candelabrum on a home altar?

No. The seven branch candelabrum has always been a part of the temple. It was so in the Tabernacle, it was so in the Temple in Jerusalem, and it remains so in the Christian Church.