It was in February 1988. It was very cold in Karyes. It was high above sea level. The humidity usually hampered our movements. But now the weather was dry. The wind was blowing and it was enjoyable if you were suitably dressed. The evening was falling. The sun had just hid beyond the mountain. Elder Paisios and I were walking along a path. We met Fr. Kallinikos from Koutlomousiou Skete on our way.

We were approaching the skete’s wooden bridge and were surrounded only by bare, lifeless hazel-trees with their bare branches.

“Hmm. Who brought me tangerines?” Elder Paisios wondered with surprise.

In the distance, over sixty-five yards away, we could make out the door of the elder’s kallyva in the yard, along with something red—or, to be more exact, something orange—hanging on the doorknob. We couldn’t see what exactly was hanging there because of the distance.

A little while later we approached the elder’s kallyva. In front of ourselves we indeed could see a large transparent, orange cellophane bag full of tangerines. How had he spotted them from so far away? How had he figured out that those were tangerines and not oranges, for example? After all, the bag was orange, and there could have been apples in it!

“Ah, I adore tangerines!” Elder Paisios said with obviously feigned greed in his voice. “I’ll take three tangerines… No, let me take five… No, if there is such a brilliant opportunity, I’d better take seven!” he said with a charming smile. “Fr. Kallinikos, please take the other tangerines and bring them to Elder Joseph who lives in front of my kallyva.”

Elder Joseph was an elderly monk who struggled at Koutloumousiou Skete. Though he was 103 years old, he would work in his kitchen garden every day.

Fr. Kallinikos received Fr. Paisios’s blessing and left. Then Elder Paisios and I entered his little cell. There he asked me to read one of his handwritten texts. About twenty minutes passed and we heard someone knock at the kallyva’s entrance door. I thought it was some pilgrim wishing to speak to the elder.

“Geronda, shall I open the door?” I asked.

“You’d better not do it. If they are curious pilgrims, they will leave soon. But if they are suffering and spiritually hungry people, they will insist on meeting with me.”

We continued our reading. A few minutes later someone knocked at the door again.

“Geronda, what shall we do this time?” I asked again.

A strip of bedsheet was hanging over his window instead of a curtain.

“Look at them from the side so that they can’t see you. And tell me how many of them there are.”

“I can’t count them. I can’t see them from here,” I replied.

“Well, did you really learn mathematics? What did you do in America for so many years? Let’s wait. They’ll knock again.”

And he was right. A few minutes later the pilgrims knocked at the door for the third time.

“Now I’ll go and try to count them. True, I didn’t finish primary school, but I’ll manage,” he said to me.

The elder stood up and opened the door of the kallyva.

“Guys, why have you arrived at this time? What have you come to me for?”

“Geronda, we want to talk with you a little. May we speak to you?”

“Yes, you may. But let me treat you to something first. How many of you are here? One, two… seven. Let’s see, what can we find in our ‘shop’ right now.”

Elder Paisios stepped back into his cell and soon came out with seven tangerines.

“What a marvelous person he is!” I thought with surprise. “How did he know how many tangerines he should leave for himself? Did he foresee this? Did God enlighten him, while he was unconscious of it?”

“Where have you come from?” the elder wondered.

“We are from Athens. Bruce and John are from the USA.”

“From the USA? So if we treat them to tangerines, the whole world will laugh at us! Let me look for something American in the ‘supermarket’.”

He left again and soon returned with a packet of American biscuits and a bag full of many varieties of nuts of a well-known American brand. Stunned, the young men expressed their amazement and were deeply impressed.

“Geronda, what does the semantron1 beaten at Orthodox monasteries symbolize?” one of them asked timidly.

“I don’t know what it symbolizes. And it doesn’t matter. The one who multiplies his God-given talents2 instead of beating the semantron is worth a lot. Listen, it is late and it’s time for you to leave. I would like to make only one remark: The problem with Americans is that in English they always capitalize the pronoun ‘I’, while we Greeks don’t always capitalize our pronoun ‘ἐγώ’ [meaning “I” in Greek.—Trans.].”

The pilgrims laughed at the funny remark and the Americans asked:

“What does it mean? What ought we to do?”

“My children, remove the word ‘ego’ from your vocabulary! Egoism is a great enemy of ours. All of us without exception should struggle against it.”

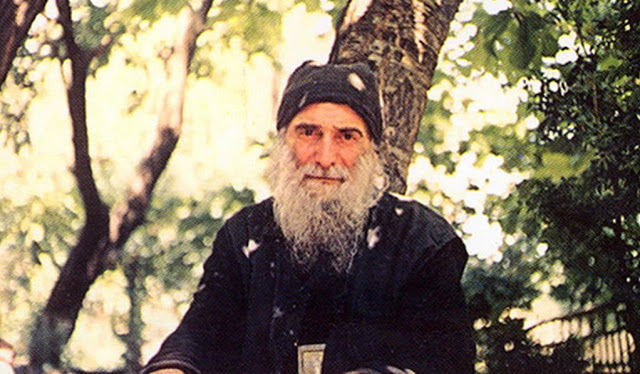

Nobility, gentleness and refinement are among the elements of holiness. Elder Paisios neither spoke about wisdom, nor pronounced theological words, nor spoke about supernatural revelations. But he did fill the hearts of all pilgrims. He would think soberly, hiding his gift of grace, treating his visitors in a courteous, beautiful, and original manner, instructing them with his words and comforting them by his presence. He would convince everybody of the greatest things without trying to convince anybody of anything. You would be enlightened, rejoice and find consolation with him. You would feel like Mary at Jesus’s feet or like the apostles on Mount Tabor (the mountain of the Transfiguration), and you would want to stay in his cell forever.

1 A semantron is a wooden or metal plank which is struck with a hammer or a stick. In ancient times it was an everyday musical instrument or else used to sound the alarm; afterwards it was chiefly used instead of a church bell.

2 In Greek the words “semantron” and “talent” are expressed by the same word, «τάλαντο».