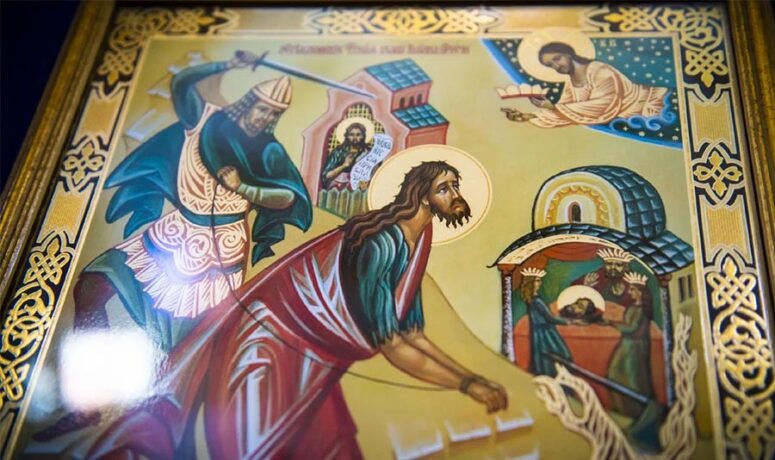

In the Orthodox calendar, few saints have as many feast days as Saint John the Forerunner. Several events in the annual liturgical circle are connected with the veneration of the precious relic, the head of John the Forerunner. His beheading, and the discovery of his head are represented in multiple works of art in Byzantine and old Russia.

So what are some of the most common ways of depicting the death of the saint? One notable work is the embroidered shroud from the late 15th century, found in the collections of the State Historical Museum of Russia. In it, the saint is shown against the background of hills and mountains, which is not consistent with the story from the Scripture. In the scripture, the place of the saint’s martyrdom is a prison cell: The Scripture (Mark (6:28), reads: “the executioner went and beheaded John in the prison” (see also Matthew 14:10). In the shroud, the prison in the scriptures was apparently represented as the tall chamber towards the right. In fact, most iconographers traditionally preferred to depict Saint John’s death amid a rocky terrain, and not in a prison cell. Perhaps this was their way of establishing a visual connection with the images of John in a desert. In the centre the shroud are the figures of the executioner wielding a bare sword and that of Saint John, bent in submission with his hands tied in front of him. His severed head is lying at his feet, with the eyes closed and a nimbus around it. The events are not shown sequentially. The saint is portrayed at the last moment of his life before the beheading.

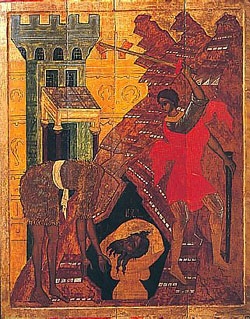

In the iconography of Saint John’s beheading, one does find examples of chronological depictions. In some, the platter with the head is shown next to the beheaded martyr, with blood still gushing from his body. But even in these examples, the head on the platter is prominent, depicted against the dark background of a cave. In the 16th century icon found in the Russian museum, the cave is at the centre of the image, and the lifeless body of Saint John is leaning towards it. Because iconographers do not utilise the techniques for representing distance and perspective like in traditional secular art, the depiction of the platter in front of a crevice indicated that it was in fact hidden inside it.

Iconographic representations of the discovery of John the Baptist’s head and the veneration of this relic should be viewed in this context. The beheading in the icon and in the shroud is not shown chronologically (as might be in the depiction of the severed head of Saint John on a platter, ready to be delivered to Herod’s feast). The depiction is symbolic: the head is shown is a revered relic that had been hidden from us several times and eventually recovered.

Separate icons dedicated entirely to the discovery of head of Saint John are quite rare. Its most common depictions are found in the fragments of the hagiographical icons of Saint John. In these icons, the larger image of John the Forerunner are encircled by numerous smaller images narrating different episodes of his life starting from his conception by the Holy Reverends Zecharia and Elizabeth and ending in the veneration of his head.

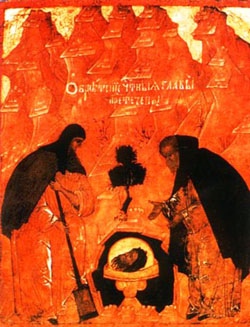

How is the finding itself portrayed? The composition of the image is similar, and most other icons follow the same pattern. The cup with the head is shown in the middle, inside a cave. Two monks of different ages are shown on both sides. One is digging the ground with a spade, the other is kneeling before the newly found relic, and extending his arms towards it. Where the short life is depicted, the scene of the finding of the head can is represented by just one image. If an icon does not contain inscriptions, or indicate the names of the monks, it is not possible to establish with full certainty which of the findings – first or second – is portrayed. Iconographic representations of the first and second findings as a single event is directly related to the fact that both are venerated on a single feast day.

Depictions of the third finding of the head of John the Forerunner, when it was delivered to the capital of Byzantine and laid to rest in the Monastery of Stoudios, are much easier to identify. Most of them show young men digging up the relic in the presence of monks and priests in vestments. One variant of the depiction found in some Byzantine icons shows a scene of church worship in front of the relic placed on the altar.

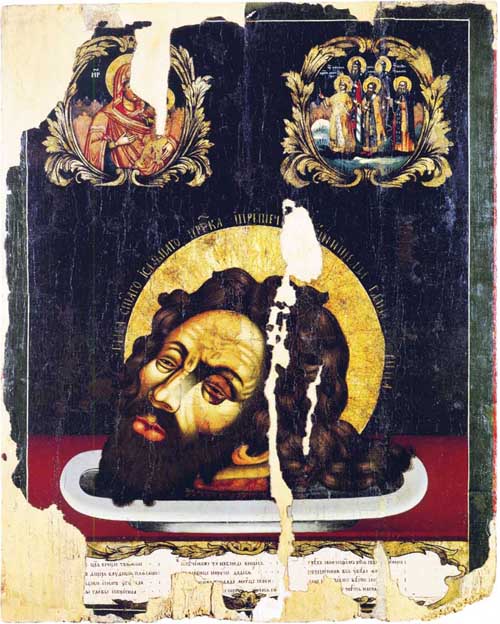

During the crusades, when the capital of the Byzantine Empire was ransacked, the head of John the Forerunner was taken out of Constantinople and brought to France. It has remained in France to this day, attracting numerous worshippers who come to the Cathedral of the Holy Theotokos in Amien to venerate the relic. In Europe, it has inspired many artists to create naturalistic naturalistic depictions of Saint John’s head placed on a platter. In Russian iconography, separate depictions of the head of Saint John the Forerunner on a platter or in a cup appeared much later, in the 18th and 19th century, as exemplified by the icon by Ivan Burenin (1762) from the collections of the Museum of Uglich.

Compiled by Svetlana Lipatova

Source: http://www.nsad.ru/articles/ikonografiya-kazni

Translated by The Catalogue of Good Deeds