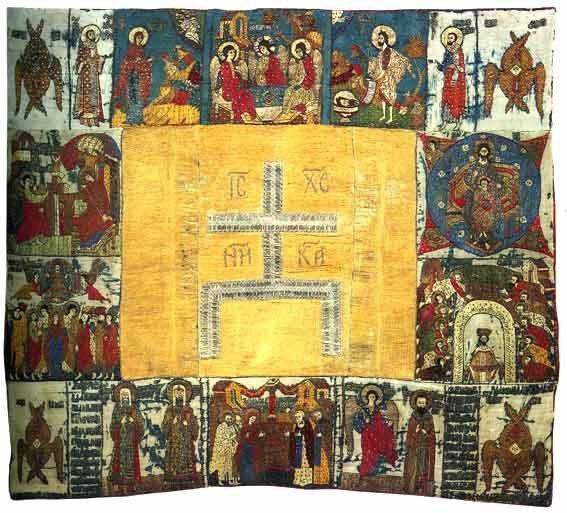

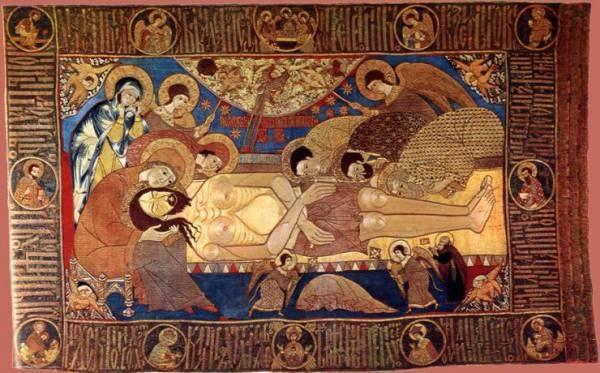

The gold-embroidered Byzantine fabrics were known in Russia even before the adoption of Christianity. It was from Byzantium with which firm diplomatic and trading contacts had been established that the tradition of pictorial embroidery came to Russian lands (before that, Russians only used ornamental embroidery). The pieces of pictorial embroidery featured biblical and Gospel themes, as well as faces of saints and scenes from their lives, and, as a rule, they were made for church use: chalice covers – small napkins for the diskos and chalice, shrouds (‘aër’, chalice veil) – the larger napkins with painted or embroidered depictions of Laying in the Tomb, Lamentation, or Deposition from the Cross), sewn icon covers, banners, garments and covers for the holy tables and oblation tables, covers for shrines with the relics of the saints, as well as vestments of the clergy; as well as embroidered icons.

Pictorial embroidery blossomed in Russia: the supreme artistic and technical skill of Byzantine craftsmen received its natural continuation in the artistic creativity of Russian artisans, maintaining and multiplying the national traditions that had been shaped up to that time.

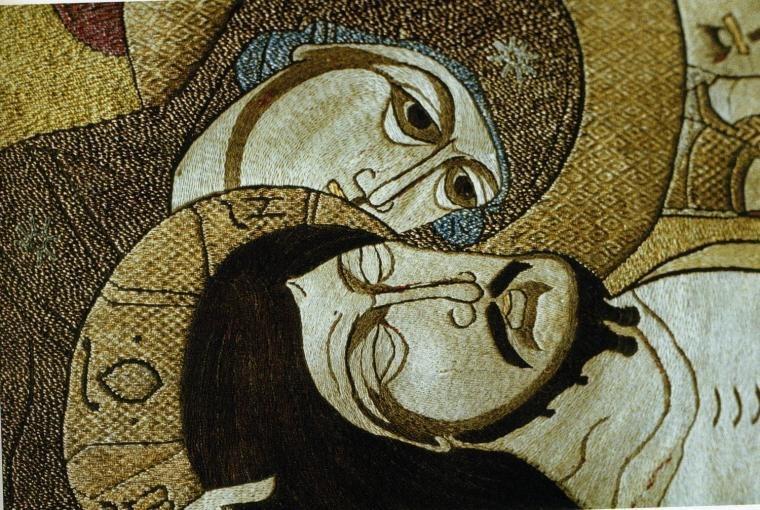

The traditions of pictorial embroidery are closely connected with iconographic and coloration traditions of ancient icon painting. An embroidery pattern was usually designed by icon painters. Simple single-color fabrics, such as damask, taffeta, silk or satin, served as a background for the embroidery. Canvas or cotton cloth was put underneath them for durability. The faces were usually embroidered with fine silk in different shades of sand color; the clothes and everything else was embroidered with silk or silver and gold threads with different stitches. Sometimes thick linen or cotton cloth was put under the gold thread to make it more prominent. The embroidered piece was often decorated with precious stones and studded with pearls. The back was normally lined.

Like in Byzantium, pictorial embroidery was manufactured in nunneries and mansions of rich princes in Russia: those were the only places where one could have the required expensive work materials imported from distant lands. The house mistress herself would be in charge of such a workshop, and she was often directly involved in its work. Depending on the economic and career position of the house master the workshop could employ as many as one hundred workers.

Traditionally, there have been Byzantine, Moscow, and Novgorod schools of pictorial embroidery. The Novgorod school is characterized by pastel colors and reduced use of gold, while the Moscow school is characterized by opulence and polychromaticity; it also uses little gold. The Byzantine school is characterized by an abundance of gold and silver threads.

There are few known examples of Russian embroidery of the 12th-14th centuries. There are some interesting fragments of women’s clothes and hats found during archaeological excavations and preserved in some museums. The cuffs of Saint Varlaam Khutynsky, an extant example of pictorial and ornamental embroidery of the 12th century, are remarkable for the elegance of their herbal (ornamental) patterns.

Dionysius and his circle had a special influence on pictorial embroidery at the turn of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Elongated proportions, refined detailed painting of faces, predominantly light colors dominated the embroidery of the first half of the 16th century. It was at this time that the art of pictorial embroidery, closely associated with icon painting, reached its peak.

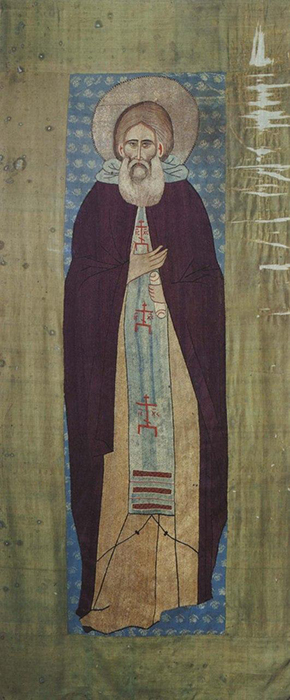

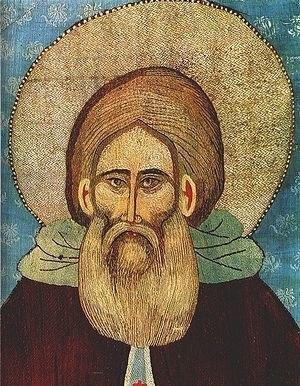

The embroidered silk coffin cloth with an image of St. Sergius of Radonezh dates back to the 1420s. Sergius stands upright, wearing strict monastic outfit. He has a very distinctive ascetical thin face of a wise elder and sunken cheeks. His slightly squinting eyes are focused on the viewer. The cover with the image of Saint Sergius was made in one of the best workshops.

The shroud made in 1561 is the best embroidered article produced in the mid-16th century in the workshop of the Princes of Staritsa. The Staritsky Shroud is notable for its excellent technique of stitching with silk, gold, and silver threads, diverse ornaments, a church hymn inscribed on the edge, written in the classic ancient font. This wonderful item later served as a model for similar shrouds created in other workshops.

The general crisis of icon painting at the end of the 17th century also led to the decline of pictorial embroidery, which was entirely concentrated around traditional Russian icon painting. The desire to imitate Western models (engravings) led to the loss of the inner, spiritual content of the image. In many ways, the new arts narrow down the circle of both the embroidered artifacts themselves and the images displayed on them. As a matter of fact, the development of new iconographic designs stops. One of the main characteristic features – the inscription – disappears. By the end of the 19th century, gold embroidery is relegated to the background, actually becoming a mere complementary decorative element.

Nowadays, the traditions of pictorial embroidery are being revived. There are specialized workshops at major spiritual centers, where this type of church art is being studied and developed. Like before, the work is made by hand using the best materials: after all, the works of art that come out of the craftspeople’s hands may endure for centuries.