The icon always depicts a person: there is not a single icon that is not anthropological in its content. Even Angels are portrayed as human beings. All animals, plants, and buildings depicted on the icon are just details of the plot, but the focus of an icon is always a human being – the God-Man Jesus Christ, the Mother of God, the saints. On the other hand, the icon is not a portrait; it does not convey the exact appearance of the depicted saint.

There are now many photographs and portraits of people who have been canonized as saints, but if you look at their icons, the similarities are minimal: icon painters strive to preserve only the most general and typical features of the saint’s appearance. The person on the icon is recognizable, but at the same time his facial traits are more refined and elegant.

There is a tradition according to which an icon painter must have an icon of the Savior in front of his eyes when he is painting an icon of a male saint, and of the Mother of God when painting an icon of a female saint. This can be explained by the fact that the icon represents a person in his or her God-like, transformed state.

This is what Leonid Uspensky says about it in his book The Theology of the Icon:

An icon is an image of a man in whom the grace of the Holy Spirit, which consumes all passions and sanctifies him, abides. Therefore, his body is depicted as essentially different from the ordinary corrupt flesh of man. The icon is a sober and spiritual experience-based transmission of a certain spiritual reality, completely devoid of any extravagance.

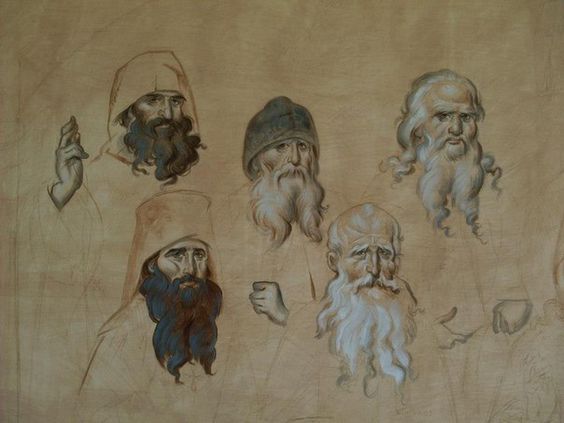

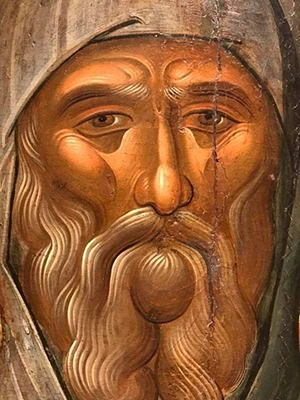

The icon shows us the transformed man. According to the Bible, man was created in the image and likeness of God (cf. Genesis 1:26). The image of God in man was distorted after the Fall. Thanks to the power of the Holy Spirit, however, the image of God in its original beauty can be restored inside man, but man himself must also take ascetic effort. An Orthodox icon becomes, to some extent, a manual on asceticism: icon painters consciously paint the arms and legs of the saints narrower and the facial features more elongated, which, to some extent, conveys those changes in the transformed flesh that occur through the ascetic feat and the power of the Holy Spirit.

If we compare the image of a human body on paintings of the Renaissance and on icons, the difference is obvious.

On most icons, the body is covered with garments that merely symbolically indicate it. There are exceptions, however, when the body is depicted almost completely naked, but in these exceptions it lacks those bodily characteristics that could cause the viewer to have passionate thoughts or arousal. The image on the icon is devoid of any visual appeal, it shows not a process, but rather the result itself: a person is depicted as not struggling with passions but as having already defeated them, not as being transformed, but as having been transformed. Therefore, another characteristic of the icon is that it is not dynamic, but static (except for the hagiographic stamps). Saints are never painted half-face: their heads are almost always full-face, or, if the plot requires it, three-quarters-face. Persons who are not worshiped, negative characters (sorcerers, Judas at the Last Supper, etc.) may be portrayed half-face. Animals (a donkey on which Christ enters Jerusalem, horses on the icon of Sts. Boris and Gleb) are always depicted half-face.

Another indication of the hallowed state of a person on the icon is that icon painters refrain from portraying any bodily defects that the person had when he was alive: for example, a blind person is depicted with his eyes open, so the icon of St. Matrona of Moscow with closed eyes is not entirely correct. Or, if the saint lacked one hand, the icon will represent him with both hands; if he wore glasses, he will be depicted without them. According to the teaching of the Church Fathers, people will get their former bodies after the resurrection, but they will be renewed and transfigured. Traditionally, icons show the dead, rather than the blind, with closed eyes: the Virgin in the scene of the Dormition, the Savior in the tomb or on the cross.

The icon does not depict pain and suffering in such a way as to cause sympathy – it has no such purpose. It should not emotionally affect the viewer; it is alien to emotions or tears. Therefore, for example, a Byzantine icon of the Crucifixion represents Christ as dead rather than in agony, in contrast to Western images. Another example is the saints during their tortures – their faces are devoid of the expression of pain and suffering. Nor do they express any kind of emotions.

The face becomes the focus of the icon in terms of its content and meaning. It is actually painted at the very end. First, an icon painter paints everything else: the background, the clothes, the setting. The background and the like are painted in several but not many layers, while the face (including hands that have special expressiveness on the icons) is painted in many layers, gradually moving from dark to light. The face was always treated with special care, usually painted by the master painter, whereas his pupils or apprentices could paint the rest of the icon. The painting of faces was particularly valuable. Eyes become the spiritual center of the face, looking not directly or away from the viewer, but a little “above” him, not into his eyes but right into his soul.

The basis of all life of the Church is the decisive and all-determining miracle of the incarnation of God and the sanctification of man. It is the icon that bears witness to the victory of man over all corruption and decay — a testimony of another plane of existence and the perspective of his relationship with the Creator.

Thank you. Excellent article. And what a joy to see the fresco of the Prophet, which is from the dome of St Seraphim of Sarov Cathedral in Santa Rosa, CA. where I serve as the rector.

You are so welcome, Father Lawrence! Thank you for your high appreciation!

“The icon does not depict pain and suffering in such a way as to cause sympathy – it has no such purpose. It should not emotionally affect the viewer; it is alien to emotions or tears.”

By this, do you mean that the icon is not made with the intention to evoke an emotional response? I certainly have been moved by icons before, though I understand the ideology behind them, particularly why those depicted saints look unmoved emotionally.

The icon can cause some specific emotions, experiences, but this is not its purpose. The text is rather about non-depicting emotions on the faces of saints, who are depicted on the icons transfigured, in a prayer state, while the experience of emotions is rather an “earthly” property of a person.

Morever, emotion is subjective, it does not convey reality objectively, truly, not biased. It conveys the point of view of a certain person. However God is certainly not comprehensible and He is certainly impossible to describe or measure.