He wasn’t a theologian and didn’t possess the charisma of a social activist, like his “competitor” for the Patriarchal throne, Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky).

He wasn’t a talented administrator and deft politician like his successor, Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky).

He wasn’t an uncompromising, fearless confessor of his convictions, like the man he appointed to be his first Locum Tenens for the Patriarchal throne, the rock of courage, St. Kirill of Kazan.

Finally, he was not even a detached ascetic, as some would have liked him to be (for example the head of the “Danilov [Monastery] Oposition” to the Patriarch, Bishop Theodore [Pozdeyevsky]).

But the faithful people loved and respected him like no other hierarch, like no other Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church after him.

So, what was the secret of his charm and his influence over generations to follow?

Patriarch Tikhon, without a doubt, was a “point of intersection” for all the Russian Church’s modern history. At him intersect all the different paths chosen by hierarchs and simple believers. Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky) in his for some sad, for others encouraging Declaration of 1927 would position himself as supposedly continuing the ecclesiastical-political course taken by Patriarch Tikhon. Those bishops who opposed Sergius would accuse the latter of departing from the “Tikhonite” line of behavior. In the emigration, those who supported the Church in the Soviet Union called it the “Patriarchal” Church. The new martyrs and confessors of Russia were glad to be in agreement with the holy Patriarch Tikhon (as Archimandrite Seraphim [Tapochkin] proudly quoted his interrogators where they described him as a “Tikhonite priest”).

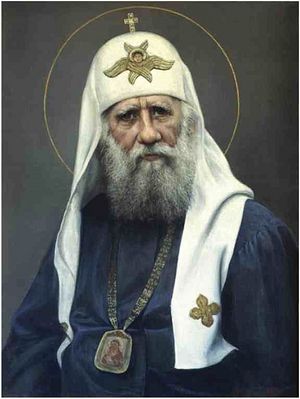

The first Patriarch after a 200-year interruption in the Patriarchy, St. Tikhon became not a church politician, but a father to his flock. This is just the kind of person the Russian Church was waiting for during that era when the entire former ecclesiastical and state order was being devastated. Nevertheless, by far not all his contemporaries—upholding all the different convictions—immediately valued His Holiness’s behavior and countenance. The renovationist “metropolitan” Vvedensky[1] called him a “weak-willed, soft-hearted character who never wielded any authority.” He wrote that, “He was never known to be an outstanding orator… In general he is just a random individual.” “He’s always laughing and petting the cat,” was the impression Bishop Theodore (Pozdeyevsky) had of him.

His Holiness Tikhon truly did not leave any impression of a majestic hierarch or brilliant “prince” of the Church. He was simple, accessible, loved to joke around, and could embellish even the most ridiculous and tragic situations with humor. In the 1920s he had a sign over his office at Donskoy Monastery stating, “Not available for questions concerning counter-revolution.”

But a great many people could perceive with a sixth sense that behind this light-hearted and humorous character was a profound inner life. People would leave their visit with the Patriarch softened and bright. Even the Red Army soldiers who guarded Patriarch Tikhon during his house arrest were continually struggling against their own sympathy for their “class enemy”. “He’s not a bad old man, but he’s always praying at night, and we can’t sleep,” recalls one of them.

But photographs of His Holiness show us that perhaps his contemporaries did not fully perceive in his face the tragedy, and mark of fate.

* * *

During an era of ideology’s dictatorial reign and its opposition, this man managed to remain absolutely remote from all ideology. His figure slips away from all labels—or maybe, to the contrary, strangely gathers them all into one.

Thus, to the synodal bureaucrats of the pre-revolutionary decade, Bishop Tikhon was a “liberal”. Of course he was… This bishop from exotic America[2] had brought back with him to the Yaroslavl diocese a democratic style of leadership and relationship to the priests under his authority. He would travel to the parishes and search out the needs of the clergy. He was always close to the “white” [that is, married, not monastic] clergy as that was the milieu in which he was raised and therefore understood their needs. In this sense Metropolitan Tikhon resembled his patron saint, St. Tikhon of Zadonsk. (There were other parallels in their lives as well: both were nicknamed “Your Eminence” and “Patriarch” in seminary, and the other seminarians would “cense” them, like they do bishops.)

He would continue in the same mode of communication with his subordinates as Patriarch. When in 1923, His Holiness was ready to bless his Church’s change to the Gregorian calendar, as he announced in his encyclical,[3] the future hieromartyr Sergius Mechev came to him and said, “Your Holiness, do not consider me a rebel, but we must not change to the new style!” The Patriarch only smiled and said, “Serezha, you, a rebel? I know you…” As a result of the Patriarch’s rethinking and other protests from the clergy, the change to the “new style” calendar was revoked… Could we ever imagine today (or any time before) an ordinary archpriest walking into the Patriarch’s reception room without any formality and declaring that he doesn’t agree with his decision? But Patriarch Tikhon really did have a fatherly relationship with his brother clergy. He listened to the opinions of people in the Church and corrected his own decisions.

At the same time, to those ecclesiastical activists of reformationist ilk, Patriarch Tikhon was an incurable conservative. From the beginning of the twentieth century (1905 to be precise—the date of Konstantine Pobedonostev’s[4] “Commentary by diocesan bishops on the question of Church reform”), when the threatening “revolutionary music” could already be heard across the country, the whole Church was astir with ideas of liturgical reform, and changes in the canonical and administrative order—understood differently by different parties. But Metropolitan Tikhon took the middle, very “balanced” path. He never was a man of “ideas”. He was a pastor. And like Kutuzov in Leo Tolstoy’s representation of him in War and Peace, in his relationship to his subordinates he preferred not to hinder anything good in them, and to avoid anything bad.

The Bolshevik victory and subsequent rapid consolidation by the OGPU of a “Red Church” in the person of the renovationists, forced St. Tikhon to veto any attempts at precocious reforms (reforms that by no means proceeded from any concern for the benefit of the flock)—even those that taken by themselves might today appear acceptable.[5] And the leaders of the renovationist movement speculated energetically on the Patriarch’s caution, definitely necessary for the moment, throwing their hated “Tikhonovshchina” overboard from the “ship of modernity”…

* * *

Out of all the candidates for the Patriarchal throne, St. Tikhon was not only the “kindliest” (as opposed to the “smartest”, Anthony [Khrapovitsky] and the “strictest”, Arseny [Stadnitsky]), but he was all around the “most humane”. His humaneness conquered all boundaries, opened the hearts of both friends and opponents, and at times went against seemingly necessary political moves.

Coming in 1914 to the Yaroslavl cathedra as a result of the shifting between him and Metropolitan Agathangel (Preobrazhensky), who was sent to replace him in America, Metropolitan Tikhon nevertheless maintained the friendliest relations with him—so much so that when Tikhon was made Patriarch, he appointed Agathangel one of his locum tenens.

When Patriarch Tikhon learned of the vengeful execution of the Royal Family in 1918, he commanded that Panikhidas (requiems) be served for Nicolas II as the slain Tsar—regardless of the fact that he abdicated the throne; regardless of the fact that under the Bolshevik terror this was dangerous for the Patriarch himself; regardless, finally, of the fact that ironically, it was the Tsarist government that had for 200 years prevented the restoration of the Patriarchy in general, and would have prevented his becoming Patriarch in particular.

In 1918, Patriarch Tikhon refused to give even his unwritten blessing for the White Army movement, although several members of the Local Council asked him for this, and he himself was issuing one threatening encyclical after another directed against the victorious powers, with anathemas against all those who bear Christian names and yet commit murder, terror, and lawlessness. God alone knows what this cost him. But, “The Church should be above politics”—which means that personal interests and hopes for political and even to some degree moral preference should be swept aside.

St. Tikhon published his “anti-soviet” encyclicals himself, during intermissions between sessions of the Local Council, showing that he bore all responsibility for these statements personally. When in the 1920s the Patriarch made concessions, announcing his position in an entirely different tone (it’s painful to read these encyclicals even now), he again spoke only for himself: “I am not an enemy of the Soviet government”. In this way, this unavoidable price he had to pay for the Church’s semi-legal existence would not weigh heavily on the conscience of the faithful.

For the sake of protecting his clergy from repression, the Patriarch was ready to make concessions even to the renovationists, who at their “council” defrocked him from both his rank and monasticism itself(!), and lead Archpriest Krasnitsky into the Synod. But in the end he reneged on this intention, convinced by the arguments of Metropolitan Kirill (Smirnov), who proved to His Holiness that “peace” with the Bolsheviks is not worth such a price and that now bishops are only fit for the prisons…

St. Tikhon demonstrated something rare for Russia—a “listening” authority; or to be more exact, a listening pastorship. But I think that he was actually listening not only to various contradictory human voices, but also to what was behind it all—the ways of God’s Providence, and His hidden guidance.

An inner tension of listening, searching, at times making mistakes and then returning to the right path were motivated by feelings of responsibility for the Church, for the flock, and for the country. Everyone who came into contact with the Patriarch could feel this. And for this, they forgave him everything.

They forgave him for proclaiming his loyalty to the soviet authorities and saying that his “anti-soviet” call of 1918-19 was the result of the “monarchistic factions” surrounding him.

They forgave him for his wavering and indecision, because they knew that it was not a matter of political maneuvering, but the torments of a conscience crucified on an invisible cross.

These torments in the end lead Patriarch Tikhon to a real, physical, and martyric death. In April 1925 he was taken to Bakuninsky hospital with heart failure. Throughout the days he was there, when he most needed peace and quiet, he was “stormed” by the soviet “Ober Procurator” for Church affairs E. A. Tuchkov, who bore no resemblance whatsoever to the religious Pobedonostev… He demanded that the Patriarch sign another, more than loyal “declaration” to the soviet regime, composed by the GPU. Metropolitan Peter (Polyansky) drove that document from Tuchkov to the Patriarch and back. Neither side could come to any agreement…

And then the Patriarch departed. Whether it was with or without the help of the GPU is no longer so important. He knew his hour and departed consciously. The details of the holy hierarch’s last day are now widely known. Washing before going to sleep, he said to his cell attendant, “The night will be long, and very dark…” He continually asked him the time. Then, at midnight, he began crossing himself reverently and broadly. The third time he was only able to lift his hand to make the sign of the cross…

And then came that very night, which he had seen as he stood on the threshold of death. A night long and dark. There were martyrs and confessors, camps, prisons, and towers with machine guns; there were bishops’ compromises with the authorities and with their own consciences, and then, the legalization of an Orthodox “ghetto” in the Nation of Soviets, then renewed persecutions and the “stagnant” years, when the Russian Orthodox Church resembled a bird in a golden cage… And then, at last—the dawn? “Watchman, what of the night?”[6]

For twenty-five years now we have grown accustomed to talking about the “spiritual rebirth” of our Fatherland, the Church, of moral and religious values… But there is a threatening prophecy ascribed by various sources to either St. Seraphim of Vyritsa (which is most likely) or to St. Barnabas of Gethsemane Skete: “The time is coming when on the one hand they will be building golden domes, but on the other, there will be a reign of lies and evil, and more souls will perish than during open theomachy.” Persecutions have not disappeared, they have only taken on a much more hidden character that is not immediately recognizable.

Over the decades following the repose of Patriarch Tikhon the Russian Church, in the person of its hierarchs and all truly concerned believers, attempted to answer the question: Which path should we take? Should we try to save the Church organization—meaning the legal, accessible divine services and Sacraments—at the price of certain “deals” with the authorities, or should we choose the path of uncompromising, but possibly unknown and as if fruitless confession of faith? In search of the answer people in the Church have, willfully or unwittingly, separated into various camps and groups—the “disagreed”, and the “Sergianists”, just as now we like to separate into “conservatives” and “liberals”… “I am of Paul, I am of Apollos…”

These questions are relevant also now, only they sound a little different: Who are we? The “reigning” Church or the persecuted Church; the Church of the New Martyrs or the Church that “speaks to the world in its own language”; the Church of power and influence or the Church of weak earthen vessels that bear within the immortal treasure of the Spirit?[7] Will we inherit the experience of New Martyrs—the experience of simplicity and poverty of spirit—or will we try to produce the same relationship between Church and society that was characteristic of the “Constantinople” period, when Christianity was welcomed and supported by external powers, but with a lower spiritual degree?

I think that the true answer lies in following Christ. Then this very following will lead each specific believer to the forms of Christian life in the world that are designed specially for him or her. After all, in the 1920s and 30s there were true confessors of the faith from both the “official” Church headed by Metropolitan Sergius, as well as from those who “disagreed”. The Church has glorified both.

* * *

In the early years, during Nero’s persecutions, the Apostle Peter was leaving Rome after wise and sober Roman Christians had convinced him that the founder of the Local Church is needed alive… Along the road, he met Christ. “Quo vadis, Domine?” Where are you going, Lord?” “To Rome, to be crucified a second time, since you have refused to do so…”

Just like the Apostle Peter, His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon wavered, was tormented by doubts, and even walked away from his own position at times. But thanks to this also, his image is dear to us. Overcoming his infirmities and constantly heeding the Grace that abode in him, St. Tikhon ascending his Golgotha, from which he sighted the future suffering of the Russian Church—suffering that he gathered into his heart, and symbol of which he became to his descendants.

Pondering this and searching for our own answers as to how a Christian must live in the modern world, one recalls the unshouting, undemonstrative, quiet courage of Patriarch Tikhon. It is the courage of a man who was well aware of his own weaknesses, but hoped always in the ineffable breath and guidance of the Spirit. It is that very courage that, when given space in the human heart, is called sanctity.

[1] http://www.odinblago.ru/istoriya_rpc/levitin_shavrov_ocherki/15

[2] Patriarch Tikhon was in America from 1898 to 1907. He was first appointed Bishop of the Aleutians and Alaska, and then in 1907 became the head of the Russian Orthodox Church in America. Upon his return to Russia he was made Metropolitan of Yaroslavl.

[3] The famous encyclical of June 28, 1923, which was the price he paid for freedom from house arrest among other things. In it was the famous sentence: “Let all monarchists and White Guards both abroad and at home understand that I am not an enemy of the Soviet government.”

[4] Constantine Pobedonostev was the “Ober Procurator” of the Holy Synod, which was the higher Church authority during the 200 years without a Patriarch.

[5] For example, allowing the reading of the priestly prayers during divine services, especially the Liturgy, which corresponds to ancient Church practice and is today practiced by a fairly large number of clergymen.

[6] Is. 21:11.

[7] 2 Cor. 4:7.