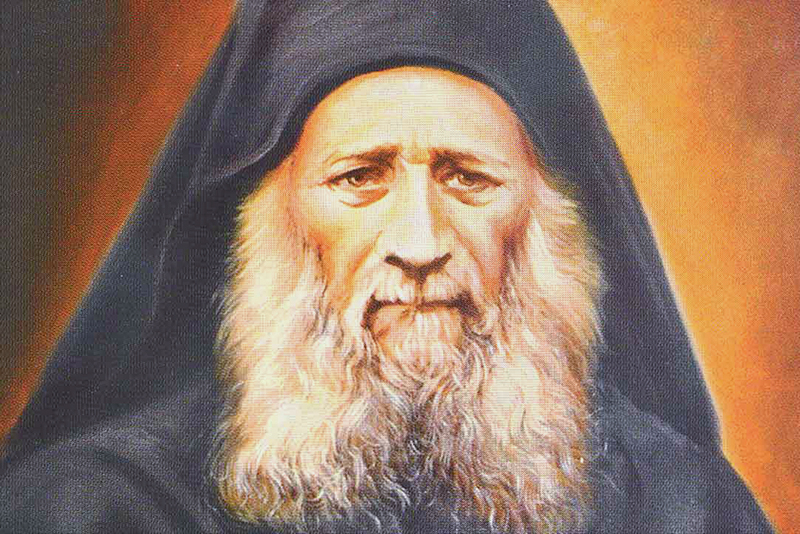

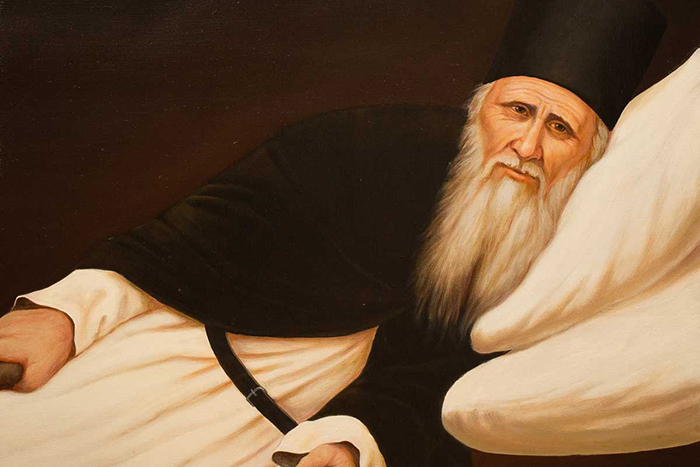

At the age of 35, Saint Ambrose of Optina became completely handicapped and could hardly move for the rest of his life; however, he continued to receive people for twelve hours every day, instructing, supporting, comforting, and helping them. From my perspective as a modern person who can hardly even think of anything if I have a headache, it is surprising and inconceivable. Because of my health issues, I’m constantly struggling to have my thoughts revolve around anything or anyone else but myself and my physical pain. On the contrary, that man spent forty-nine years in service to people; all his contemporaries who saw him and had a unique opportunity to communicate with the elder, noted that he was filled with all-embracing love for people. It was this love that attracted crowds of ordinary people and intellectuals to him, rather than his perspicacity and miracles. It is estimated by contemporary physicians that Father Ambrose suffered so much pain that it would have killed another person in a week. As for him, he became a saint.

A young, well-educated man who spoke five languages suddenly became terminally ill. He swore that if he survived, he would go to the monastery. The disease subsided, but the man was slow in carrying out his vow for another four years – it was difficult to part with worldly life. His condition deteriorated again, causing him to go to the monastery at last. Alexander becomes a hieromonk but after a few years he loses all ability to officiate and participate in long monastery services, and ends up “off service” of the monastery. Before that, he had spent many years in the Publishing House of the Optina Pustyn, and served as a secretary for Elder Macarius (Ivanov). All the dozens of letters to the elder passed through his hands every week; he also recorded the elder’s answers to those letters. It was a kind of pastoral training: each letter represented a specific situation, a specific human fate and experience. After the death of the elder, Father Ambrose began to manage the publishing activities of the monastery, focusing not on publishing ascetic books of the Holy Fathers, but on the real monastic experience of the monks of the monastery itself.

But that’s not probably why he became the most famous Russian elder: it was his love of humanity and simple wisdom that attracted people to him. I guess any Orthodox person knows and loves the elder’s aphorisms and sayings, which are easy to understand and remember. Of course, he used this method of communication not just to make jokes, but to encourage people and reach their hearts.

It seems to me that nowadays we neglect simplicity and trivial things; for Father Ambrose, nothing was too insignificant. He could interrupt a theological discussion and start talking to a simple woman about turkeys because he was able to see through the heart of a person and recognized what was important and necessary for that particular person.

It may have been this profound feeling of love and empathy that filled the elder with courage before the Lord and made him a source of real miracles. One day, Elder Ambrose was returning to the skete, bent and leaning on a stick. Suddenly he saw a loaded cart, a dead horse lying next to it, and a peasant crying over the horse. The loss of a horse was a major disaster in the life of a peasant. The elder came close to the fallen horse and started moving slowly around it. He took a twig, and hit the horse, shouting at it: “Get up, you lazybones!” and the horse obediently rose to its feet.

Being able to understand everybody is such a rare talent nowadays. We often want to make people think about the things that we consider important rather than about their hearts. Is it easy to empathize with others? Definitely not. Empathy is even less achievable when your body aches and you feel helpless all the time. I don’t feel like saying that each misfortune can teach you to feel compassion, because there is a chance that you will become angry or lose all your humanity. Perhaps there is a unique talent to turn this punishment into a gift and teach a person who suffers to understand oneself better, while at the same time being able to understand and accept the other person. Elder Ambrose possessed this talent, and his selfless life was a consolation and healing for many distressed and miserable people. He was a true beacon of God’s love.