The Divine Liturgy is the most important divine office. There are countless articles and books describing it. In the same way that the Liturgy is versatile, its history is also multifaceted, so there are quite a few facts that only a handful of people seem to know about the Liturgy. Let’s find out what we don’t know about the Divine Liturgy.

There are a whole lot of books and papers that deal with the symbolism of the Liturgy: The Entrance with the Gospel is said to symbolize the beginning of the Lord’s public ministry, while the entrance with the Chalice before the Communion of the Faithful supposedly symbolizes the Apparition of the Risen Christ. Whilst I’m aware of the importance and didactic value of this method of explaining the Liturgy, I suggest that we step away from it and examine historical approaches, given that many parts of the Liturgy appeared as a result of its practical development and was assigned sacred meaning retroactively. To do so, we will have to travel in time to Constantinople, for it was there that our Liturgy gained its contemporary form.

How does a Liturgy start today? We go to church in the morning and listen to the Hours, then a deacon comes out and exclaims, Bless, Master! Looks familiar, huh? Things worked differently in Constantinople, however. There were lots of churches in honor of saints or holidays in Constantinople. That was why patron saint’s days in those churches were led by a bishop.

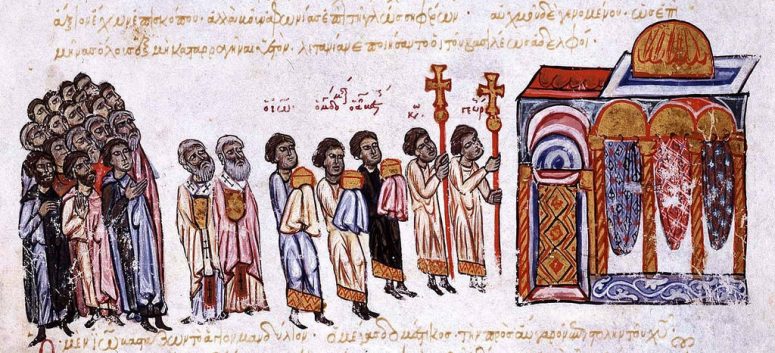

People would gather in the central square of the city early in the morning and proceed to the church, singing solemn hymns. The solemn hymns were the three antiphons that we hear either on weekdays or on great holidays. A lead singer sang a biblical verse, and the choir of the people responded to it with a chorus, e.g., By prayers of the Theotokos, O Savior, save us or Save us, O Son of God, Risen from the dead, for we sing thee: Hallelujah. That is to say, the Liturgy started on the way to the church, not inside it.

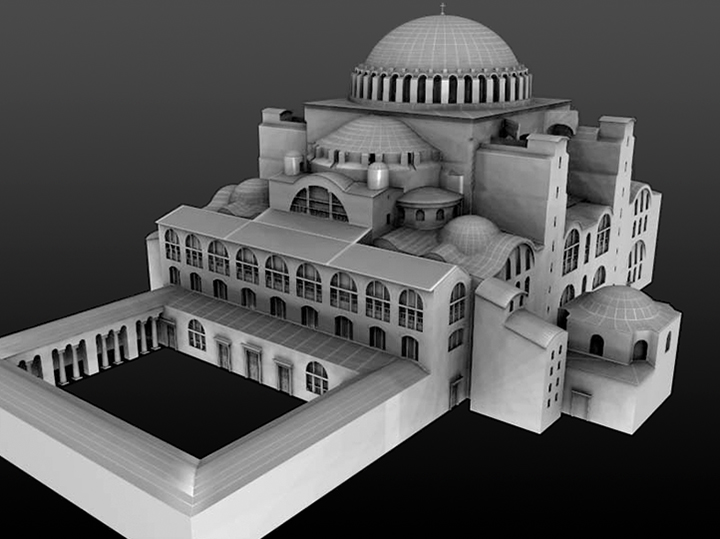

When the procession made it to the church, the clergy and the faithful, and often even the emperor, gathered outside of the church in a church yard, where they read a solemn prayer of entrance. All people entered the church singing a hymn, such as the Trisagion. When the emperor arrived at the church, they would sing a verse from Psalm 20, “Save, Lord: let the king hear us when we call.” They would also bring the Holy Gospel in the church at the same moment. The Gospel book was usually preserved in a special building called sacristy.

I suppose that you have recognized several parts of our contemporary Liturgy, i.e., the solemn entrance with the Gospel, the singing of the Trisagion, and the exclamation O Lord Save The Pious (the Greeks did not have the emperor after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 so they modified the exclamation).

Later, the processions stopped. The antiphons were sung in the church and the solemn entrance to the church was replaced by the solemn entrance of the clergy from the sanctuary into the nave but the hymns that had been used in earlier times remained.

Let’s go back to Byzantium. After the entrance to the church, the bishop would walk to the sanctuary and ascend to the High Place. Nowadays, the High Place is the east wall of the sanctuary, but it used to be a literal high place in the east side of the church, which the bishop climbed so that all the faithful could see him. It was from there that he greeted everyone else, Peace to All! – which marked the beginning of the Liturgy proper.

The pastoral greeting was followed by the reading of the Holy Scripture. Today, we are accustomed to the fact that the Holy Scripture is read either in the sanctuary or close to it, or – only in the cases when the Liturgy is celebrated by a bishop – it is read in the middle of the church. Reading in ancient times always took place in the center of the nave, on a special elevation called ambo. Currently, an ambo is the central part of the entrance to the altar but then it was a tall (sometimes as tall as 6.5 ft, e.g., in Novgorod) tower, which a reader or a deacon climbed to proclaim the Word of God.

The bishop would preach a sermon immediately after the Gospel reading. Originally, he preached from the High Place but then, since St. John Chrysostom time, bishops usually preached from the ambo.

The sermon was followed by a prayer for everyone who needed it. A deacon would name the needs to be prayed for and the faithful would respond with Lord have mercy, sometimes more than once. That was how our litanies came to be.

Subsequently, there were prayers for those who were not allowed to stay in the nave any longer, i.e., for catechumens, penitent sinners, and the possessed. They were allowed to stay only during the first part of the Liturgy and had to leave the church after being blessed.

As soon as they left the church, the Liturgy of the Eucharist started.

People would bring their offerings to the church before the service, including bread and wine. They laid those offerings in a special building outside of the church, which was called sacristy. Deacons and other clerics took bread and wine from that building.

When all catechumens and penitents left the church, some of the clerics would leave the church through a side door and go to the sacristy to bring the Holy Gifts while the remaining clergy led by the bishop were reading prayers before the beginning of the Eucharist and wash their hands. The clerics took bread and wine, along with necessary vessels, and returned to the church through the side door, where they were met by servers carrying candles. The clerics passed through the entire church, praying for those who had brought their offerings, and then gave the bread and the wine to the bishop.

You might guess that it was the origin of our Great Entrance. Then they started preparing the bread and the wine in the sanctuary, and thus the ritual of bringing the Holy Gifts into the church transformed into a symbolic procession with the prepared Gifts from the Oblation Table to the Holy Table.

Next, the Byzantines had the kiss of peace ritual, when everyone present at church greeted each other with a kiss. Later, that ritual gave way to joint profession of faith, i.e., the singing of the Symbol of Faith.

Immediately afterwards, the anaphora was read. The anaphora is the main prayer of the Liturgy, in which we remember the Last Supper and ask the Lord to send his Holy Spirit onto us and onto our offering of bread and wine, and transform them into the True Body and Blood of Jesus Christ.

It’s time we talked about the names of our liturgical rites. Everyone knows that they are called the Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom and the Liturgy of Saint Basil the Great. Most people believe that those saints were the authors of the current liturgical rite and wrote all prayers and hymns of those services. Of course, that’s not the case. The Liturgy was being developed for two millennia. There were parts of the Liturgy and prayers that entered the Liturgy centuries after St. John and St. Basil and could by no means belong to them. Why are they listed as the authors of our Liturgy? That is because (and most scholars support this point of view) they wrote the central prayer of the Liturgy – the anaphora – and that was why the respective Liturgies were named after them.

Back to the Liturgy. As soon as the anaphora was over, people got ready for receiving the Eucharist and sang Our Father. After the Lord’s Prayer, all who didn’t plan to partake of the Holy Mysteries on that day, left the church after a special prayer and a blessing. That is precisely why a deacon says, Bow your heads before the Lord after the Lord’s Prayer. The deacon takes communion every time, so he doesn’t bow his head. Those who do are the people who are not going to take communion and who are going to leave the church after the special prayer and the blessing.

We have merely scratched the surface of the history of our Liturgy. Naturally, we didn’t delve deep into the ins and outs of this service. There are dozens of research papers and monographs devoted to each part and even each hymn of the Liturgy. They investigate the origins of this or that part of the service in tiniest detail. However, even our brief account can give you an insight into the origins of some parts of the Liturgy and how they were incorporated into our contemporary service. I hope that it will help us to pray during this most important service of the Orthodox Church more consciously and attentively.