Volumes have been written on spiritual membership, but this topic still attracts the interest of the laity and clergy. Not every ordained priest can be a spiritual father, but spiritual guidance is essential to being a good shepherd of one’s flock. A priest can be a good mentor for some but not others, and not every Christian is an obedient spiritual child. In this piece, we examine what the history and practice of our Church can teach us about choosing a spiritual mentor.

Spiritual mentorship

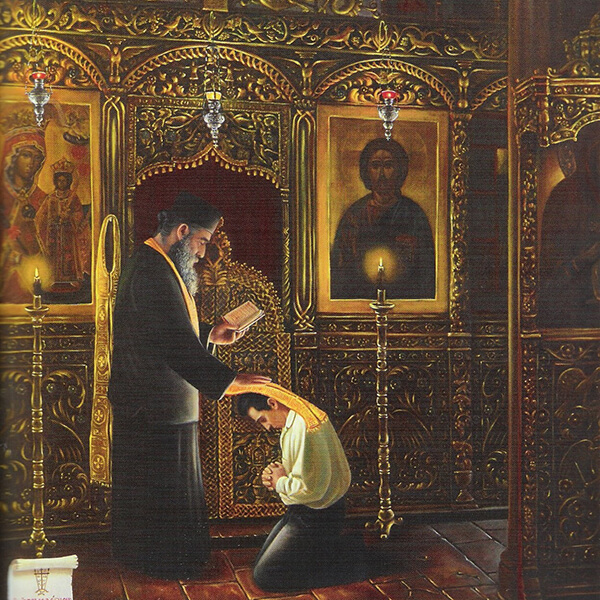

In church life, a spiritual mentor is an active priest who undertakes the journey to salvation with his spiritual children. He performs the absolution of sins in the sacrament of confession, guides his disciples in their progress towards spiritual unity with God and helps them live their lives according to the Gospel and the Church Tradition. Over time, the spiritual father and child form a deep spiritual connection grounded in love, trust, prayer and Communion.

Lessons from church history

The practice of spiritual mentorship comes from Christ Himself, who shed His ultimate love on all humans and worked tirelessly for man’s salvation. He helped the Holy Apostles grow in their faith. The Apostles passed on the gifts of the Holy Spirit to the next generations of their followers. Their apostolic service still lives in the good works of the contemporary elders. Yet only a few of these spiritual members rose to the likeness of Christ.

Byzantine

In the Byzantine era, the clergy were figures of unquestioned authority. Spiritual membership was reserved only for the most mature and experienced priests known for their righteous lives and abbots of monasteries. Spiritual fathers needed to take a separate ordination from a bishop with the laying of hands, the reading of a dedicated prayer receive an authorisation. No priest could perform the duties of a spiritual father without these prerequisites. The churches of Greece and old Russia inherited this tradition from Byzantine.

Greece

The Greek Church still grounds its practices in the Byzantine tradition inherited from ancient times. Its sacrament of Confession remains separate from Communion. For the Greek faithful, confessions are less frequent but more profound. Believers reserve the time for their confessions in advance. Alexander Nosevich, a Greek priest, explains: “The relationship between the confessor and the penitent are those of the father and child. The confessor must possess extensive spiritual experience and wisdom. A simple ordination is not enough. Despite his education and capabilities, a new priest must acquire the spiritual experience to become a mentor by assimilating the spirit of the church to become a channel of God’s grace.” Only when a priest becomes well versed in church life, he may approach the bishop for ordination as a spiritual father. In practice, that cannot happen any earlier than after three years of service.

Russia

Russia adhered to the Byzantine tradition until the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The Nomocanon of the Great Trebnik established that a believer had the free choice of a confessor, but could not change his spiritual father afterwards. A believer was also forbidden to approach another priest to lift a penance imposed by his chosen confessor. The confessor and his spiritual children formed “penitent families”, which typically included monks and white priests and played a prominent role in the propagation and strengthening of the faith among the Russian people. Members of such families facilitated each others’ progress in the faith and took care of the needs of their confessors.

Russia’s territorial expansion from the sixteenth century onwards created a shortage of clergy. The deficit was so large that cases of involuntary ordinations were not infrequent. The requirement of a separate ordination for spiritual mentors was lifted, but the inconsistent level of education and pastoral skills fuelled the demand for a new type of confessor – the Starets, endowed with special wisdom and unique experience.

From the eighteenth century, the education of the clergy took considerable priority. Religious schools and academies sprang up across the land, and numerous writings were produced about the work of the parish priests. Yet the education and skills of the regular priests remained inconsistent, drawing growing numbers of believers to choose their spiritual guides among the elders. The tradition of the elders blossomed in Russia between the 18th and 20th centuries. For a long time, elders served as a model of the relationship between the spiritual father and child.

Education and ordination alone do not make you a spiritual mentor

Despite numerous well-educated clergy, finding a suitable spiritual mentor is still a tough call. The problem is common in parishes and communities in countries with majority Orthodox populations and in those where the Orthodox are a religious minority.

Three stages of advancement to spiritual mentorship

Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh identified three steps in the ladder of advancement to spiritual mentorship. He also cautioned the inexperienced clergy against taking on the roses for which they were not prepared spiritually.

He placed the newly ordained parish priest on the first step of his ladder. Their ordination, qualifies them to perform the sacrament of confession and the absolution of their sins. They are not expected to act as spiritual guides or offer advice during confessions.

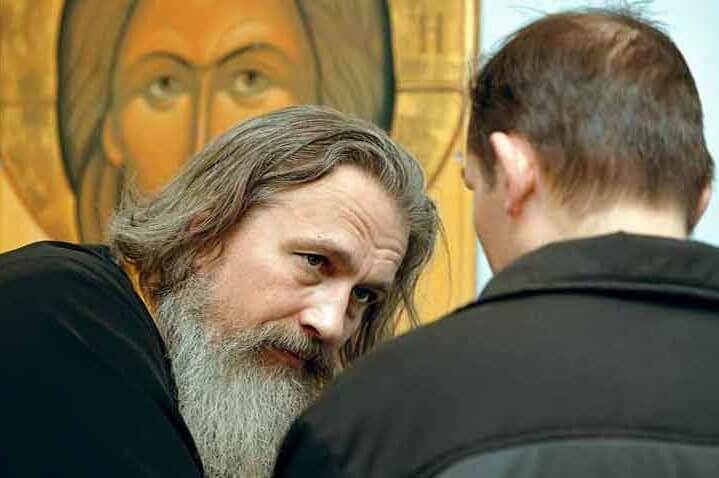

Priests with some experience of spiritual and parish life and familiarity with their parishioners’ spiritual and daily lives are on the second step. They are in a position to give guidance to their flock from their knowledge and personal experience. When they cannot answer a question, they should acknowledge their ignorance. They should pray that God will reveal to them the right answer and advise the parishioner to do the same.

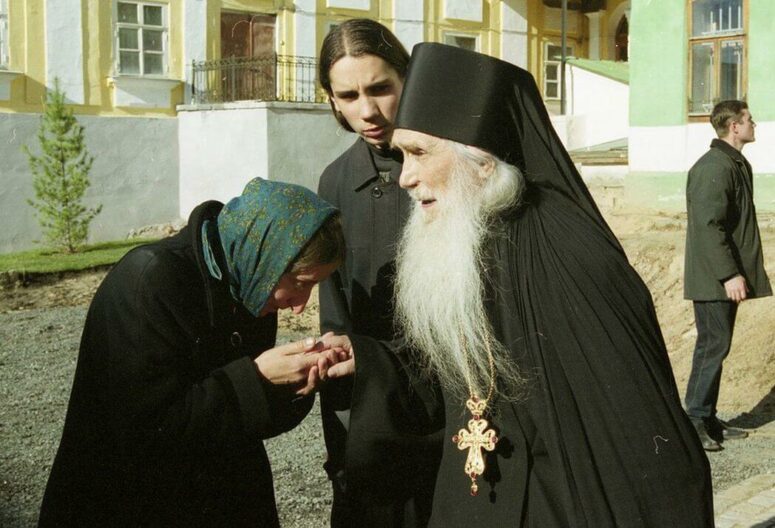

On the third step of the ladder are the elders. They have likened themselves to Christ with their lives and have a calling to lead their flock to the Kingdom of God. They can look into the heart of the person who comes to them and enlighten them on some aspects of God’s plan for them. But no one can claim to be an elder arbitrarily. Elders reveal themselves to the world when the Grace of God touches their souls, and they respond to this calling by taking on the feat of mentorship and spiritual guidance.

Genuine elders are very rare. There are many more who claim to be elders unreasonably. Therefore, the Orthodox elders would be well advised not to limit their search for a spiritual mentor exclusively among elders. It is possible to find an appropriate guide among the clergy whom Anthony of Sourozh assigned to the second step of his famous ladder. The challenge is to find a mentor that suits our individual needs and circumstances and build a productive spiritual relationship that leads us to salvation.

The attributes of a spiritual mentor

To be a guide for others, a priest must first heal himself. “A priest can only become a spiritual leader for others in their journey to Christ if he keeps working on one’s spirit and follows in good conscience the path of self-improvement as a Christian,” wrote Bishop Tikhon (Belavin) to a newly ordained priest.

A priest should also remember that his role as a spiritual member rests on his trust in God. In the words of Saint Ignatius (Bryanchaninov), “we are only instruments of the Divine Providence. We are nothing by ourselves; without God’s help, we cannot give guidance to anyone, not even to ourselves. So every spiritual mentor must lead people to Christ, not to himself.” Unless the relationship between the mentor and disciple is grounded in Christ, it will bring ruin to both souls.

All spiritual mentors should have Christ and His apostles as their models. Only then could they build their relationship with their disciples on love, compassion and forgiveness and redeem their sins like Christ redeemed the sins of all humanity on the Cross.

The relationship between the spiritual father and child should rest on love and trust. That implies obedience on the part of the spiritual child and benevolence and respect for their children’s free will – with which God had endowed them – on the part of the spiritual father. In the words of Saint John Chrysostom, a spiritual mentor observes the condition of his disciple’s soul from every angle. For the spiritual mentor, this means advising his disciple on opposing the enemy with full knowledge of his inner and outer life.

So how should a Christian look for the right confessor?

First, he must pray that God would send him a spiritual father. “Pray vehemently and tearfully that God will send you a pious and passionless mentor,” advises Saint Simeon the New Theologian. “We must carefully examine every candidate to understand if we are close enough in the spirit,” continues the saint. We should compare their recommendations with the teachings of the Scripture and the Holy Fathers, accepting everything that coincides with these teachings and rejecting everything that does not.”

Finally, when we find the right confessor, we should disclose to them our gravest and subtlest sins with trust and obey their directions as fully as possible to benefit from our relationship.

To summarise, priests have learned spiritual life from their spiritual fathers and their experience of God and His church. Any experienced priest can become a spiritual mentor for a believer if both have the correct understanding of the nature of their relationship. But we must choose our mentor sensibly, and if we cannot find one, we must still trust God and His providence. God does not always need a mentor to communicate with us.

Read also: How to Distinguish True Elders and Prophets from False Ones