In the Bible we read that in the beginning, God created heaven and earth, and that the earth was unstructured (“unsightly” or “unfurnished,” as the Holy Bible says), and that the Life-giving Spirit of God moved silently above it, infusing the earth with living powers.

In the Bible we read that in the beginning, God created heaven and earth, and that the earth was unstructured (“unsightly” or “unfurnished,” as the Holy Bible says), and that the Life-giving Spirit of God moved silently above it, infusing the earth with living powers.Great Vespers, the beginning of the All-night Vigil, takes us back to this dawning of creation. The service begins with a silent making of the sign of the cross with the censer before the Holy Table and the censing around the Holy Table in a cross fashion. This action is one of the most profound and significant moments in all of Orthodox worship. It is an image of the movement of the Holy Spirit within the essence of the Holy Trinity. The very silence of this censing gives us an indication of the Divine eternal rest, which was from before the world existed. It symbolizes the fact that the Son of God, Jesus Christ, Who sends the Holy Spirit from the Father, is the “the Lamb, sacrificed from the creation of the world.” Similarly, the cross, the weapon of His saving sacrifice, also has an eternal, cosmic, pre-creation significance. In one of his homilies for Great Friday, the 19th Century Metropolitan Philaret of Moscow emphasized that “The Cross of Christ . . . is the earthly image and shadow of the heavenly Cross of Love.”

The Beginning

After the censing, the priest stands before the Holy Table, while the deacon, having gone through the Beautiful Gates (Royal Doors) to the ambo, stands facing the West (that is, toward the faithful), and announces: “Upright!” (“Arise!”) Then, turning to the East, he continues “Bless, Master!”

The priest makes the sign of the cross with the censer before the Holy Table, and says “Glory to the holy, consubstantial, life-creating, and indivisible Trinity, now and ever, and unto the ages of ages.”

The meaning behind these words and actions rests in the fact that the deacon, concelebrating with the priest, invites those who have gathered here to stand at prayer, to be attentive, and to “take heart.” Then the priest confesses the Beginning and Creator of all, the consubstantial and life-creating Trinity. At the same time, in making the sign of the Cross with the censer, the priest demonstrates that it was through the Cross of Jesus Christ that Christians were made worthy to comprehend to some extent the mystery of the Holy Trinity in God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit.

After the doxology “Glory to the holy . . .” the clergy within the altar glorify Jesus Christ, the Second Person of the All-holy Trinity, by singing “O Come let us worship God our King . . . the very Christ, our King and God.”

The Proemial Psalm

Then the choir sings verses from the Proemial Psalm, Psalm 103, beginning with the words “Bless the Lord O my soul,” and ending with “In wisdom hast Thou made them all.” This psalm hymns the universe created by God, the visible and invisible world, and has been an inspiration to poets from among many different peoples and historical periods. An example is the well known restating of the psalm in verse by the poet Lomonosov. Its themes also resound in Derzhavin’s ode entitled God, and in the Prologue to the Heavens by Goethe. The principal feeling imbuing this psalm is man’s admiration for and contemplation of the beauty and harmonious arrangement of the world made by God. God “brought order” to the unformed earth during the six days of creation. Everything became beautiful (God saw that it was good, Genesis 1:10; cf.12,18,21,25 [LXX]). The 103rd psalm also expresses the idea that even the least noticeable thing in nature holds within it the most wondrous of wonders.

Censing of the Church

The censing of the entire temple takes place during the singing of this psalm while the Beautiful Gates are still open. This practice was introduced into the Church so that the faithful might be reminded of the movement of the Holy Spirit above God’s creation. The open Beautiful Gates at this point are a symbol of paradise; that is, of the state in which the first people lived in direct communion with God. Immediately following the censing of the temple, the Beautiful Gates are closed, just as Adam’s ancestral sin closed the gates of paradise to man separating him from God.

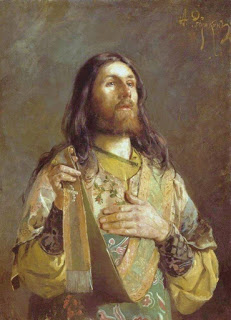

All the rituals and hymns at the beginning of the All-night Vigil reveal to us the cosmic significance of the Orthodox temple; the temple, which represents a true image of the structure of the world. The altar and the Holy Table represent paradise and heaven, over which the Lord reigns. The clergy represent the angels who serve God. The central part of the temple represents the earth and man. The clergy descend from the altar and to the faithful in much the same way paradise was returned to man by the redeeming sacrifice of Jesus Christ. They wear shining vestments as a reminder of the Divine Light with which the garments of Christ shone on Mount Tabor.

The Lamplighting Prayers

The Beautiful Gates are shut immediately after the priest censes the church, as a reminder that with Adam’s ancestral sin, the gates of paradise were shut to him, and he was estranged from God. Now fallen man, standing before the closed gates of paradise, prays for a return to the path to God. The priest, representing the repentant Adam, steps before the closed Beautiful Gates. Standing there as an image of repentance, with head uncovered, and without the resplendent phelonion in which he had celebrated the festive beginning of the service, he silently reads the seven Lamplighting Prayers. These prayers, composed in the 4th century, make up the most ancient part of Vespers; in them we hear man’s recognition of his helplessness and his plea for direction on the path of truth. The prayers are characterized by lofty eloquence and spiritual depth. The seventh prayer states:

“O God, great and most high, Who alone hast immortality and dwellest in light unapproachable; Who hast fashioned all creation in wisdom; Who hast divided between the light and the darkness, and has appointed the sun for dominion of the day, the moon and stars for dominion of the night; Who hast counted us sinners worthy at this present hour also to come before Thy Countenance with thanksgiving, to offer unto Thee our evening glorification: do Thou Thyself, O man-befriending Lord, direct our prayer as incense before Thee, and accept it for a savour of sweet fragrance. Grant us peace in the present evening and the coming night; array us with the armour of light; deliver us from the terror by night, and from everything that walketh in darkness; and grant us sleep, which Thou hast given for the repose of our infirmities, free from all diabolic imagining — yea, O Master of all, Bestower of good things: so that we, being moved to compunction upon our beds, may call to remembrance Thy Name in the night, and being enlightened by the meditation on Thy commandments, we may rise up in joyfulness of soul to glorify Thy goodness, offering up prayers and supplications unto Thy loving kindness, for our own sins and for those of all Thy people, whom do Thou visit in Thy mercy, through the intercessions of holy Theotokos. . . .”

It is Church practice that during the reading of these lamplighting prayers, the candles and lamps within the temple are lit, an action that symbolizes the hopes, revelations, and prophecies in the Old Testament regarding the coming Messiah, our Savior, Jesus Christ.

The Great Ektenia

Next, the deacon chants the Great Ektenia. An ektenia or litany is a series of short prayerful requests or pleas addressed to the Lord, regarding the worldly and spiritual needs of the faithful. An ektenia is an especially fervent prayer read on behalf of all of the faithful. The choir, also acting on behalf of all of those present at the service, responds to these petitions with the words “Lord have mercy,” a phrase which, while short, is nonetheless one of the most perfect and complete prayers which can be uttered by man. It says all that there is to say.

Next, the deacon chants the Great Ektenia. An ektenia or litany is a series of short prayerful requests or pleas addressed to the Lord, regarding the worldly and spiritual needs of the faithful. An ektenia is an especially fervent prayer read on behalf of all of the faithful. The choir, also acting on behalf of all of those present at the service, responds to these petitions with the words “Lord have mercy,” a phrase which, while short, is nonetheless one of the most perfect and complete prayers which can be uttered by man. It says all that there is to say.The Great Ektenia is known for its opening words; “In peace let us pray to the Lord,” is, thus, also known as the Litany of Peace. Peace is an essential condition for any prayer, whether an individual or a communal church prayer. In the Holy Gospel according to Mark, Christ speaks of the spirit of peace as the basis for any prayer: And when ye stand praying, forgive, if ye have ought [anything] against any: that your Father also which is in heaven may forgive you your trespasses (Mark 11:25). St. Seraphim of Sarov said “Acquire the spirit of peace, and thousands around you will be saved.” This is why at the beginning of the Vigil, and in most services, the Church invites the faithful to pray to God with a calm, peaceful conscience, having reconciled ourselves to our neighbor and to God.

Further on in the Litany of Peace, the Church prays for peace throughout the world, for the unification of all Christians, for our native land, for the temple in which the service is taking place, and in general for all Orthodox churches, and for them that enter the temple, as the litany says, “with faith, reverence, and the fear of God,” but not for them that enter out of curiosity. We remember those who travel, the sick, the imprisoned, and we hear a request to be saved from “all tribulation, wrath, danger, and necessity.” In the closing petition of the Litany of Peace we state: “Calling to remembrance our all-holy, immaculate, most blessed, glorious Lady, Theotokos and Ever-virgin Mary with all the Saints, let us commit ourselves and one another and all our life unto Christ our God.” This formula encompasses two profound and basic Orthodox theological concepts: the dogma of the prayerful intercession of the Mother of God at the head of all of the Saints, and the lofty ideal of Christianity; the dedication of ones life to Christ our God.

The Great Ektenia or Litany of Peace ends with the priest’s doxology, which, just as at the beginning of the Vigil, glorifies The Holy Trinity; Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

The Psalter

As Adam stood repentant before the gates of paradise and prayed to God, so, the deacon stands before the closed Beautiful Gates and begins the Great Ektenia with the words: “In peace let us pray to the Lord. . . .”

Adam, however, had just heard God promise that the seed of the woman would bruise the head of the serpent and that the Savior would come into the world, so Adam’s heart burned with the hope of salvation.

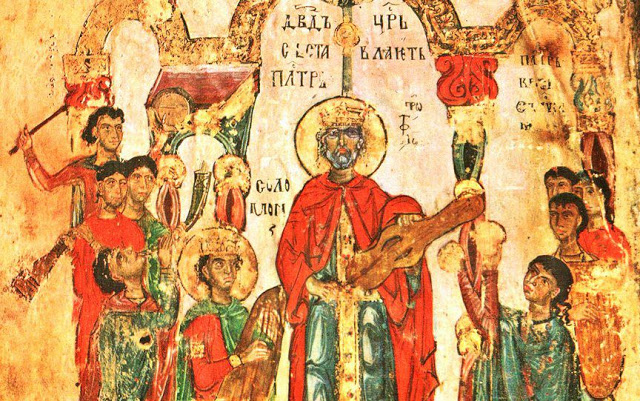

This hope is expressed in the All-night Vigil in the hymn which follows. As if in answer to the Great Ektenia, a biblical psalm is heard: “Blessed is the man…” This Psalm, the first psalm of the Psalter, embodies a direction and warning to the believer against taking erroneous, sinful paths in life. In monasteries, and in some churches, not only the first psalm, Blessed is the Man, but the entire first kathisma of the Psalter is chanted. The Greek word kathisma means “seat” or “stall,” because, according to Church rules, it is permitted to sit during the readings of the kathismata. The Psalter, which consists of 150 psalms and is divided into 20 groups of psalms known as kathismata. Each kathisma in turn is divided into three parts, or “Glories,” for each part ends with the words “Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit.” The entire Psalter, all 20 kathismata, are read over the course of the services in a week. During Great Lent, the 40-day period preceding Pascha, a period during which Church prayer intensifies, the Psalter is read twice each week.

The Psalter was incorporated into the liturgical life of the Church in the earliest days after the Church was established. It occupies a position of great honor within Church life. St. Basil the Great, writing in the 4th century, stated:

“The Book of Psalms includes useful material from all of the books. It has prophesies regarding the future, it calls to mind past events, it sets out the laws of life, and it offers rules for action. The Psalms bring peace to the soul and order to the world. The Psalter quenches restless and troubling thoughts . . . is comfort from daily toils. The Psalm is the voice of the Church and is perfect theology. . . .”

In his book In the World of Prayer, Protopresbyter Michael Pomazansky writes about the significance of the Psalter in Orthodox worship:

“Within the Church, the Psalter is, so to speak, Christianized. Here, many Old Testament concepts and expressions take on a new, more complete, meaning. For this reason, the Holy Fathers and spiritual strugglers love so to use the words of the Psalter, which speaks about defense against our enemies, and expresses their thoughts on the battle with the enemy of our salvation and with the passions.

“Thus it is no surprise that the Psalms take up such a large part of divine worship services. Each service begins with psalms; some with only one, but most with three. An enormous number of verses from the Psalter are to be found throughout all of the liturgical cycles.”

After the first psalm is sung, the Small Litany is chanted: “Again and again in peace let us pray to the Lord.” This ektenia, a shortened form of the Great Ektenia, contains two petitions:

“Help us, save us, have mercy upon us, and keep us O God, by Thy grace.

“Lord, have mercy.

“Calling to remembrance our all-holy, immaculate, most blessed, glorious Lady Theotokos and Ever-virgin Mary with all the Saints, let us commit ourselves and one another and all our life unto Christ our God.

“To Thee O Lord.”

The Small Litany concludes with the priest’s reading of one of the doxologies appointed in the order of service.

It is known from the history related in the Bible that the voices of sorrow and hope, which had first cried at the gates of paradise after the fall into sin of our first created parents, continued to sound until the very coming of the Christ.

In the Vigil, sinful man’s sorrow and repentance is expressed in the verses of the penitential psalms, which are sung to special melodies and with particular solemnity.

Lord, I Have Cried and the Censing

After the singing of Blessed is the Man, and the Small Litany, we hear the verses from Psalms 140 and 141, psalms beginning with the words “Lord, I have cried unto Thee, hearken unto me.” These psalms, which relate fallen man’s longing for God and his striving to truly serve God, constitute the most characteristic, distinguishing feature of any Vesper service. In the second verse of Psalm 140, we encounter the words “Let my prayer be set forth as incense before Thee” (a prayerful sigh that is known for its especially moving musical setting in the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts sung during Great Lent). The censing of the entire church takes place while these verses are sung.

What does this censing signify?

The Church answers through the words of the psalm already mentioned: “Let my prayer be set forth as incense before Thee, the lifting up of my hands as an evening sacrifice,” that is to say, may my prayer ascend unto Thee [God], like smoke from the censer, and may the raising of my hands be as an evening sacrifice to Thee. This verse reminds us of that time in the ancient past when, according to the Law of Moses, in the evening of each day a sacrifice was offered in the tabernacle (tent of meeting), that is, in the portable temple used by the people of Israel while they were moving from the bondage of Egypt to the Promised Land. The sacrifice was marked by the lifting up of the hands of one bringing the sacrifice, and by the censing of the altar that contained the Holy Tablets of the Law, which had been received by Moses from God on the summit of Mt. Sinai.

The ascent of the smoke from the burning incense symbolizes the prayers of the faithful, ascending to Heaven. When the deacon or priest censes in the direction of the faithful, they respond by bowing their heads, as a sign that they recognize it to be a reminder that the prayer of the believer, like the smoke of incense, easily rises up to Heaven. Censing the people also reminds us of the profound truth that the Church sees in each person the image and likeness of God; a living icon of God, as it were, and sees the betrothal to Christ received in the mystery of Baptism.

During the censing of the church, the singing of “Lord I have cried . . .” continues and our corporate parish prayers join in offering the sentiment of this psalm, for we are no less sinners than were our first parents. From the depths of our hearts, we, together with them, cry out the words “Hearken unto me, O Lord.”

The Stichera for Lord, I Have Cried

Among the following penitential verses of the 140th and 141st psalms is “Bring my soul out of prison . . .” and, from the 129th Psalm, we hear “Out of the depths I have cried unto Thee, O Lord, O Lord, hear my voice.” Later, voices of hope in the promised Savior resound from the chanter.

Hope amid sorrow is heard in the two hymns that follow Lord, I Have Cried, the so-called Stichera for Lord, I Have Cried. While the verses preceding the stichera speak of darkness and sorrow of the Old Testament, the stichera themselves (those refrains which supplement the verses), speak of the joy and light of the New Testament.

Stichera, liturgical songs composed in honor of a feast or a saint, are of three types:

1) Stichera for Lord, I Have Cried which as we have already noted are sung at the beginning of Vespers;

1) Stichera for Lord, I Have Cried which as we have already noted are sung at the beginning of Vespers;

2) those sung at the close of Vespers between verses taken from the Psalms, known as Aposticha; and 3) those toward the close of the second part of the vigil, sung together with psalms wherein the invocation “Praise ye” is often encountered. These are known as the Stichera for the Praises.

The Resurrection stichera glorify the Resurrected Christ and festal stichera tell of the reflection of His glory in various sacred events or spiritual struggles of the saints; for ultimately, all of church history is tied to Pascha and to

Christ’s victory over death and hell. By following the sticharion text, one can recognize who or what event is being commemorated and glorified in the services of the day.

Christ’s victory over death and hell. By following the sticharion text, one can recognize who or what event is being commemorated and glorified in the services of the day.

The Octoechos

Like the Psalm Lord I Have Cried, the stichera are also a distinguishing feature of the All-night Vigil. In Vespers, between six and ten stichera are sung in a specific tone. Since antiquity, there have been eight tones, composed by St. John of Damascus, who struggled spiritually at the Lavra (monastery) of St. Sabbas the Sanctified in Palestine during the 8th century. Each tone encompasses several melodies to which specific prayers in the divine services are sung. The tones change weekly. The cycle of the so-called Octoechos moves through the eight tones over the course of eight weeks, and then begins anew. All of these melodies are contained in the liturgical book known as the Octoechos or the Book of Eight Tones.

The tones are one of the most outstanding features of Orthodox liturgical music.

Dogmatika

The Nativity of the Son of God was the answer to the repentance and hope of the people of the Old Testament. A special Theotokion sticheron, sung immediately after the stichera for Lord I have cried, tells us of this. This sticheron is known as a Dogmatikon or a Theotokion-Dogmatikon. There are eight dogmatika; one for each tone. The dogmatika are comprised of praises of the Theotokos and the teachings of the Church about the incarnation of Jesus Christ and about how His two completely distinct natures; divine and human, dwell in Him.

What sets the dogmatika apart is their profound catechetical meaning and their sublime poetry.

Here is an English rendering of the Dogmatikon in the First Tone:

“Let us hymn the Virgin Mary, the glory of the whole world, who sprang forth from men and gave birth unto the Master, the portal of heaven, and the subject of the hymnody of the incorporeal hosts and adornment of the faithful; for she hath been shown to be heaven and the temple of the Godhead. Having destroyed the middle wall of enmity, she hath brought forth peace and opened wide the kingdom. Therefore, having her as the confirmation of our faith, we have as champion the Lord born of her. Wherefore, be of good courage! Yea, be ye of good cheer, O people of God, for He vanquisheth the foe, in that He is almighty!”

This Dogmatikon sets forth, in concise form, the Orthodox teachings about the human nature of the Savior. The principal theme of the Dogmatikon in the first tone is that the Mother of God was born of common people, and herself a common person, and not a superhuman. The common people of whom she was born, though sinful, preserved their spiritual essence to the extent that, in the person of the Mother of God, they were worthy of taking the Divinity, Jesus Christ, into their heart. The Holy Fathers of the Church taught that the all-holy Theotokos is man’s justification before God. In the person of the Mother of God, humanity was raised to heaven; and God, in the person of Jesus Christ, Who was born of her, came down to earth. This, considered from the perspective of Orthodox Mariology (teachings with respect to the Mother of God), is the actual purpose of Christ’s Incarnation.

The English translation of the Dogmatikon in the Second Tone declares:

“The shadow of the law passed away when grace arrived; for, as the bush wrapped in flame did not burn, so did the Virgin give birth and yet remained a virgin. In place of the pillar of fire, the Sun of righteousness hath shone forth. Instead of Moses, Christ is come, the salvation of our souls.”

The meaning of this Dogmatikon lies in the fact that through the Virgin Mary, grace came into the world and liberated the faithful from the weight of the Old Testament law, which was a mere shadow and symbol of the future good things of the New Testament law. The Dogmatikon in the Second Tone also underscores the ever-virginity of the Theotokos, depicted in the Old Testament symbol of the burning bush that was not consumed. This burning yet unconsumed bush was the thorn bush which Moses saw at the base of Mt. Sinai. According to the Bible, the bush burned but was not consumed, that is, it was engulfed by flame, but did not burn.

The Little Entrance

The singing of the Dogmatikon at the Vigil represents the uniting of earth and heaven. During the singing of the Dogmatikon, the Beautiful Gates are opened to show that heaven, in the sense of man’s communion with God, which was closed by Adam’s sin, was opened once more with the coming to earth of Jesus Christ; the Adam of the New Testament. At this point, the Evening or Little Entrance takes place. The priest, preceded by a deacon, comes out of the altar through the North (deacon’s) door, just as the Son of God, preceded by St. John the Forerunner, appeared to man in the world. The choir concludes the evening/little entrance by singing the prayer O Gentle Light, portraying in words what the priest and deacon have portrayed in the action of the entrance; the gentle, humble Light of Christ, which appeared almost unnoticed in the world.

O Gentle Light

O Gentle Light (rendered as O Gladsome Light by some) is known, in the cycle of chants of the Orthodox Church, as the evening hymn, since it is sung at all the vesper services. In the words of this hymn the children of the Church “having come to the setting of the sun, having beheld the evening light, we praise the Father, Son and Holy Spirit; God.” It is apparent from these words that the chanting of O Gentle Light was intended to coincide with the appearance of the soft light of sunset, a time when the soul of the believer should be close to feeling the touch of another kind of light, a light from above. This is why, in ancient times, Christians, on observing the setting of the sun, poured out their feelings and turned in prayerful attitude of soul to their Gentle Light, Jesus Christ, Who is described by the Apostle Paul as the brightness of the glory of the Father (Hebrews 1:3) and by the Old Testament prophet as the true Sun of Righteousness (Malachi 3:2[LXX]), and the true light which according to the Holy Evangelist John appeared in the world to dispel spiritual darkness (John 1:4,9); a light which is eternal, an unsetting sun.

St. Cyprian of Carthage, who lived in the 4th century, wrote “Inasmuch as Christ is the true sun and the true day, when we pray at the setting of the sun and ask that light to come to us, we are praying for the coming of Christ, who possesses the grace to offer us eternal light.”

The prayer, O Gentle Light, which appeared in the epoch when the Church of Christ was in the catacombs, is the third distinguishing feature of the Vespers. O Gentle Light also contains one of the most important of Orthodox dogmas, the confession of Christ as the visible face of the All-holy Trinity, a dogma which is the foundation for the practice of venerating icons.

Let us attend

After the chanting of O Gentle Light, the clergy serving in the altar make several short exclamations: “Let us attend,” (The Church Slavonic word вонмем—vonmem [this article is translated from Russian] is an imperative form of the verb “to heed.” It is translated here as “Let us attend” but could be translated “Let us pay heed.”) “Peace be unto all,” and “Wisdom.” These exclamations are made not only during All-night Vigil, but during other services as well. These liturgical exclamations, though repeated several times in church, can easily pass us by unnoticed. They are little words, but they their content is great and significant.

In our daily life, to be attentive or heedful is important. Yet the capacity to be attentive or heedful does not always come easily. Our intellect is predisposed to being forgetful and unfocused. It is difficult to force oneself to be attentive. The Church is aware of our weakness, and so it takes it upon itself to remind us with the phrase, “Let us attend!” which tells us: let us be attentive, let us be heedful, let us take note, let us be careful, let us gather our wits, and let us strain to focus our mind and our memory on what we are hearing. Even more importantly; let us so set our hearts that nothing going on in church will slip by us. To be attentive or take heed means to unburden ourselves, to free ourselves of memories, empty thoughts, and concerns; or, to use an expression from our liturgical language, to “put aside all earthly cares. . . .”

Peace be unto all

The little exclamation, “Peace be unto all!” is first heard during the All-night Vigil immediately following the small entrance and the prayer, O Gentle Light.

Among ancient peoples, the word peace was a form of greeting. The Romans used the word pax as a greeting, while devout Jews to this day greet one another with shalom. This form of greeting was used during the earthly life of the Savior, as well. The ancient Hebrew word shalom has a variety of meanings and caused New Testament translators considerable difficulty until they ultimately settled on the word eirini, Greek for “peace.” The word shalom has several shades of meaning in addition to its direct meaning. For example, it can mean “to be complete, healthy, and unharmed.” Its fundamental meaning is a dynamic one. It means “to live well,” to have wellbeing, to be healthy, satisfied, and so on, and is to be understood both in the material and the spiritual sense, and both individually and communally. Figuratively, the word shalom meant good relations among various individuals, families, and peoples, between man and wife, and between man and God. For this reason, its antonym or opposite meaning was not necessarily war, but most likely was everything that could interrupt or destroy individual wellbeing or good communal relations. In this broader sense, the word peace, shalom, represented a special gift given by God to Israel for the sake of His Covenant; His agreement with them. For this reason, the word was employed in an entirely specific, even priestly way, as a blessing.

The Savior used this word in precisely this sense as a greeting. He greeted the apostles with it, as St. John states in his Gospel: “The first day of the week [after the Resurrection of Christ] . . . came Jesus and stood in the midst, and saith unto them [His disciples] and saith unto them: Peace be unto you (John 20:19). Then said Jesus to them again, Peace be unto you: as my Father hath sent Me, even so send I you (John 20:21). This was not simply a kind of formal greeting such as we so often hear in ordinary human discourse. Here Christ actually sends His disciples out into the world, knowing that they are to go through the abyss of hatred, persecution, and martyric death.

This is that peace of which the Apostle Paul spoke in his epistles, the peace not of this world, that peace which is one of the fruits of the Holy Spirit; that peace which is of Christ; 14For he is our peace (Ephesians 2:14).

This is why during services the bishops and priests so often bless the people of God with the sign of the Cross and with the words “Peace be unto you!”

The Prokeimenon

The Προκειμενον — Prokeimenon follows the greeting of the faithful with the words of the Savior’s greeting, “Peace be unto you.” The Prokeimenon is a short passage taken from the Holy Writ and is read along with one or more other stichos — verses that supplement the meaning of the Prokeimenon. The Sunday Prokeimenon, in the sixth tone, is read during Vespers on Saturday evening; the eve of the Resurrection. The Resurrection is commemorated every Sunday. The Russian word for Sunday, Воскресенье — Voskresene, literally means Resurrection. The Prokeimenon is read first in the altar, then repeated by the choir.

The Readings

The Readings or Paremia, which literally means “lessons,” consists of a passage or passages from the Old or the New Testament. The Church has decided that readings such as these, which contain prophecies or words of praise about the event or saint being commemorated, should be read on eves of great feasts. While three readings are usually read, from time to time there are more; such as, on Great Saturday, the Eve of Pascha, or one of the fifteen other special days of commemoration.

The Augmented Litany

Christ’s coming into the world, which is shown to us in the action of the evening small entrance, shows the closeness of God to man and strengthens their prayerful communion. This is why immediately after the prokeimenon and the readings, the Church invites the faithful to intensify their prayerful communion with God through the Augmented Litany. The several petitions in the Augmented Litany remind us of the content of the first vesperal litany or ektenia; the Great Ektenia. However, the Augmented Litany also includes prayers for the reposed. The Augmented Litany begins with the words “Let us all say with our whole soul and our whole mind. . . .” The choir responds to each petition for all of those praying, with a thrice repeated “Lord have mercy.”

Vouchsafe, O Lord

The prayer, Vouchsafe, O Lord, is read after the Augmented Litany. A portion of this prayer, which was composed in the Syrian Church during the 4th century, is read in the Great Doxology during Matins.

The Litany of Supplication

The concluding Litany of Supplication is chanted immediately after the prayer, Vouchsafe, O Lord. After the first two petitions, the choir responds to the remaining petitions with Grant this, O Lord, which makes the requests bolder than does Lord have mercy; the penitential response heard in the earlier litanies. In the initial litanies of Vespers, the faithful pray for the welfare of the whole world and the Church; that is, for external welfare. In the Litany of Supplication, we hear prayers for success in our spiritual life; that is, for a sinless conclusion to the day; for an angel of peace; for pardon and remission of our sins; for a Christian and peaceful ending to our life, and, and for a good defence before the dread judgment seat of Christ.

The Prayer at the Bowing of Heads

After the Litany of Supplication, the Church calls on the faithful to bow their heads unto the Lord. At this moment, the priest addresses God with a special secret or hidden prayer, which he reads silently. It contains the idea that those who have bowed their heads expect help not from men, but from God, and they ask Him to guard the faithful from every enemy, external, and internal; from vain thoughts and from evil imaginings. The Bowing of the Heads is an external sign that the faithful put themselves under God’s protection.

The Litiya

On great feasts and on days commemorating highly honored saints, the Bowing of the Heads is followed by the Litiya or Service of Entreaty. The term Лития — Litiya means intensified prayer. It begins with the singing of special stichera in honor of the feast or saint of the day. As the singing of stichera begins, the clergy go in procession through the north (deacon’s) door of the iconostasis, and out of the altar. The Beautiful Gates remain shut. A candle is carried at the head of the procession. When the litiya is celebrated outside of the church building; for example, during times of civil distress or on days marking liberation from such distress, the litiya is incorporated in a Moleben and Procession of the Cross. Also a Memorial litiya may be done in the narthex after Vespers or Matins.

Michael Skaballanovich, a pre-Revolutionary liturgist, writes that “in the litiya, the Church steps out of its blessed milieu and, with the goal of mission to the world, into the external world or narthex; that part of the church which abuts this world, the part which is open to all, including those not yet part of the Church or are excluded from Her. From this stems the universal character of the litiya prayers, embracing all people.”

During the litiya, the deacon reads the prayer, Save, O God, Thy people, as well as, four other short petitions. These are comprised of entreaties for the salvation of the people, the Church and civil authorities, for the souls of Christians, for the cities, for this land and all believers living herein, for the reposed, as well as, entreaties asking that we be preserved from foreign invasions and from civil war. Each of these five petitions, chanted by the deacon, ends with repeated chanting of Lord have mercy.

During the litiya, the faithful display a heightened sense of humility. In the litiya, a host of saints are invoked by name, underscoring one of the basic dogmas of Orthodoxy; our veneration of, and prayerful communication with, the saints.

The words Lord have mercy are repeatedly chanted during the litiya; which causes the heart, mind, and soul of those who pray to be saturated with this petition. These multiple repetitions are intended to focus our attention on the meaning of the prayer, something the Church considers especially important for man’s spiritual growth. Like a musical theme, this oft repeated prayer accompanies us out of the church and into our daily life.

Lord have mercy — only three words; yet how profound! First of all, in calling God Lord, we affirm the fact of His rule over the world, over mankind; and, the most important, over ourselves, and over those who call Him Lord, which means “ruler” or “master.” For this reason we refer to ourselves as servants or slaves of God. There is nothing shameful about this title. Slavery is intrinsically a negative thing, for it robs man of his earliest gift from God, the gift of freedom. Since it is a gift given by God to man, man’s serving God is in fact the acquisition of perfect freedom in God. It is good to treasure, keep, and cultivate the prayer, Lord have mercy.

After the deacon has read the petitions and the priest has read the prayer, O Master plenteous in mercy, and during the singing of the Aposticha, which consists of stichera or verses that glorify the feast or saint of the day; the clergy and faithful enter the nave or central part of the church. At this time, a table is placed in the center of the church. On the table are five loaves of bread, as well as, wheat, wine, and oil. All are then blessed in this token act of the ancient custom of distributing food to the faithful, some of whom had come from afar, so that they might gain the strength to participate in the lengthy worship services. Five loaves are blessed in memory of the Lord’s feeding of the 5000 who listened to his sermon. Later, during Matins, and after the faithful have venerated the Festal Icon, the priest anoints them with blessed oil.

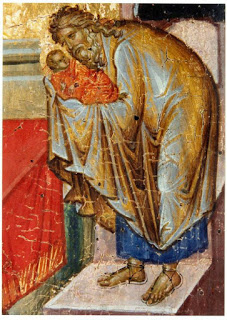

The Prayer of St. Symeon, the God-receiver

The Prayer of St. Symeon, the God-receiver, Now lettest Thou Thy servant departs in peace, O Master is read after the Aposticha. St. Symeon uttered these words when he received the Divine Infant Christ in his arms in the Temple of Jerusalem on the fortieth day after Our Lord’s Nativity. In this prayer, the Old Testament elder thanks God for enabling him, before his death, to see Salvation; that is, to see Christ, Who was given by God for the glory of Israel, and for the enlightenment of the gentiles and of the entire world. In English, the prayer says: “Now lettest Thou Thy servant depart in peace, O Master, according to Thy word, for mine eyes have seen Thy salvation, which Thou hast prepared before the face of all peoples; a light of revelation for the nations, and the glory of Thy people Israel.”

Vespers, the first part of the All-night Vigil, is now drawing to a close. Having begun with a commemoration of the opening pages of Old Testament history, the creation of the world; it ends with the prayer. Now lettest Thou Thy servant depart, symbolizing the conclusion of the history of Old Testament.

The Trisagion

Immediately following the prayer of St. Symeon the God-receiver, the Trisagion or Thrice-Holy prayers are read. They include the prayers Holy God, All Holy Trinity, and Our Father, and end with the doxology exclaimed by the priest For Thine is the kingdom. . . .

Following the Trisagion, the Troparia or Dismissal Hymns are sung. A troparion is a short, concise hymn honoring the saint being commemorated or about the holy event being celebrated that day. The distinguishing feature of the troparion is that it concisely describes either the person being glorified or an associated event. At the Resurrection Vespers on Saturday evening, the troparion to the Mother of God O Theotokos and Virgin, rejoice! is sung three times. This troparion is sung at the conclusion of Resurrection Vespers because of the joy of Christ’s Resurrection, the focus of Matins that follows, announces the joy of the Annunciation when the Archangel Gabriel advised the Virgin Mary that she was to give birth to the Son of God, effectively marking the end of Old Testament times. The words of this troparion are composed mostly of the words of greeting spoken by the archangel to the Mother of God.

In the event that a litiya is part of the All-night Vigil, the priest or deacon moves around the table, on which the loaves of bread, and the wheat, wine, and oil are placed; censing them three times as the troparion is being sung three times. Then the priest reads a prayer which asks God to “bless the bread, wheat, wine and oil, and multiply them throughout the world and to enlighten those who eat of them.” Before reading this prayer, the priest slightly elevates one of the loaves, and having punctured its surface with his thumb, makes the sign of the Cross with it over the remaining loaves. This action is done in remembrance of Christ’s miraculous feeding of the 5000 with five loaves of bread.

In the past, the bread and wine which were blessed were then distributed to the faithful in order to strengthen them for the service of the All-night service, which in fact continued for the entire night. In contemporary worship, the blessed bread is cut into small pieces to be given to the faithful later, as they are the anointed with oil during Matins; this will be expanded upon later. The solemn ceremony of the blessing of the loaves dates back to a practice of the earliest Christian times, and is a remnant of the Agape or Love Feast observed by those first Christians.

At the conclusion of the litiya, in recognition of God’s mercy, the choir sings “Blessed be the Name of the Lord from henceforth and forevermore.” This is also the concluding sticheron of the Divine Liturgy.

The priest closes Vespers, the first part of the All-night Vigil, blessing the faithful from the ambo with the ancient blessing in the name of the incarnate Jesus Christ, with the words, “The blessing of the Lord come upon you, by His divine grace and love for man, always, now and ever, and unto the ages of ages.”

An excerpt from: https://www.fatheralexander.org/booklets/english/vigil_v_potapov.htm