Today monastic life has spread over the whole world; but many years of effort were needed to achieve this. The movement began, as we have seen, in Egypt, where important monastic centers, with thousands of monks, rapidly developed, the monks living in cells, lavras, and monasteries. These were situated at the Thebaid, Nitria, Sketis, Tabenesis and Mount Sinai. The monastery of St. Catherine on Sinai, founded during the time of Justinian, has survived with undiminished vigour to the present day. From Egypt it spread very rapidly to Palestine. This country, sanctified as it was by the life and death of the founder of the Christian faith, attracted the interest of ascetics from all corners of the Empire, of the Latins Jerome and Rufinus became renowned. Later, great lavras were established there, about five hundred in number, by Theodosius the Coenobiarch, Savvas the Sanctified, and Euthymius the Great.

Ascetics appeared in Syria during the first decades of the fourth century. They were usually itinerant men and women, the latter garbed like men. They sought to abolish all differences between the sexes, and avoided work. Because of the dominant position which they gave to prayer, they were called Euchites, or, in the Syriac, Massalians. They were criticized by the Church for certain deviations. At the same time, the milder, organized form of monasticism also reached Syria. The great hymnographer and theologian Ephraim the Syrian also made successful efforts to organize the monks.

Ascetics appeared in Syria during the first decades of the fourth century. They were usually itinerant men and women, the latter garbed like men. They sought to abolish all differences between the sexes, and avoided work. Because of the dominant position which they gave to prayer, they were called Euchites, or, in the Syriac, Massalians. They were criticized by the Church for certain deviations. At the same time, the milder, organized form of monasticism also reached Syria. The great hymnographer and theologian Ephraim the Syrian also made successful efforts to organize the monks.Monasticism began to lose ground in these three countries from the beginning of the seventh century, that is, from the time of the Arab conquest; but it never disappeared completely. Today, besides the Orthodox, the Copts, Jacobites, Armenians, and Nestorians also have monasteries.

By way of Cappadocia and Asia Minor, monasticism reached the capital of the Empire, Constantinople. Many of the monasteries that were established in the suburbs on both sides of the Bosporus became flourishing organizations, and through their activities influenced the course of ecclesiastical and sometimes of political affairs. The monastery of the Sleepless Ones, which was founded by Alexander about 430, received its name from the fact that the monks praised God throughout the entire day and night, being divided into three groups which succeeded one another in church. The monastery of Studion, likewise founded in the fifth century, by the Roman patrician Studius, became the center of the liturgical development of the eastern Church and the champion of its independence of state intervention. Theodore the Studite, who flourished at the beginning of the ninth century, became through his heroic conduct an exemplar for all monks.

In these regions monasticism was definitely destroyed during the period of Turkish conquest.

Strong centers of monasticism had already been formed, however, in Greece. Among these, Mount Athos was distinguished from the tenth century onwards, and henceforth called the “Holy Mountain”. In 963, the emperor Nicephoros Phocas issued a decree, granting to the monk Athanasius the right to found there a great lavra, which he did. Within a short time other communities of monks were founded here, and these were placed under the general supervision of the Protos. In order to further the spread of monasticism there, Alexius Comnenus placed all the establishments of Athos under the jurisdiction of the nearest bishop, that of Ierissos. But understandably friction occurred between him and the Protos, and for this reason it became necessary to abolish the jurisdiction of the bishop of Ierissos. This was done towards the end of the fourteenth century.

The Protos of Athos was installed after approval had been obtained from the Patriarch of Constantinople. At first he was appointed for life, and lived at Karyes, the capital of the monastic commonwealth. He dealt only with the general external problems of the community, because the monasteries remained internally self-governing.

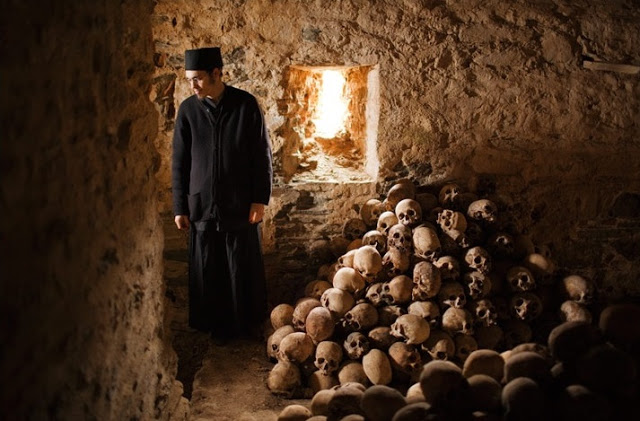

The dwelling places of the mountain are placed in an environment at once impressive and serene. The increase of piratical raids after the weakening of the Byzantine empire and the Turkish conquest influenced their architectural construction. The monasteries are built like powerful fortresses, with towers and embrasures. The cells are constructed on top of the fortress wall, three, and even six stories of them. In the middle of the courtyard there is a “katholikon”, or central church, with chapels around the sides.

Long foreign occupation caused many fluctuations in the power and vigour of these establishments. Today the land of this self-governing region is divided up among twenty self-sufficient monasteries. One representative of each monastery, elected annually, is sent to Karyes, where the Holy Community, a kind of parliament, meets. The monasteries are divided into five groups of four, each headed by one of the strongest monasteries: Lavra, Vatopedi, Iviron, Hilandari, and Dionysiou. Each group takes it in turns to exercise administrative for one year at a time. Thus, of the twenty representatives, four constitute the executive body, the committee of overseers, while the representative of the first monastery of the group which has the administrative initiative is the chief overseer. Each overseer keeps one-fourth of the seal of the monastic commonwealth.

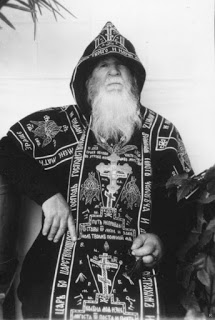

Eleven of the monasteries of the Mountain, mostly on its western side, are coenobitic, and are governed by an abbot who is elected for life and has a council of elders to advise him. Nine, for the most part on the eastern side, are idiorrhythmic, governed by a committee of three superiors (proistamenoi) who are elected for one year. The monastery of Hilandari is Serbian; that of ographos, Bulgarian; that of Panteleimon, Russian. There is also a Rumanian skete. The monastery of Iviron, which is now Greek, was formerly Georgian (Iberian). Until the thirteenth century there was the Latin monastery of the Amalfitans. Thus, the Holy Mountain became a symbol of the catholicity and unity of Orthodoxy; and it is still the chief monastic center of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, and is unique in its kind in the entire Christian world. Unfortunately there has been a decline in the number of monks for many now, which reduces the vigour of monastic life there.

During the years of the Despotate of Epiros, Meteora became a celebrated monastic center. Impressive monasteries were built above steep cliffs, looking from a distance like eagles’ nests; and many small hermitages were hewn out of the rock. Until a few decades ago, access to some of these monasteries was possible only by windlass and net. Of the twenty-four ancient monasteries of that region only four function today, with a small number of monks. Many monasteries still remain and continue to function throughout Greece, but with an ever decreasing number of monks.

From the East the monastic life was brought to the West, as early as the fourth century. It flourished there particularly during the Middle Ages, when strong monastic orders were organized. These played a large part in Christianizing and civilizing the peoples of northern Europe. Monasticism was also transmitted, together with Christianity, to the countries north of Greece: to the Slavs, the Rumanians, and other peoples. The Russian monastic leaders Antony and Sergios became famous. The elder ascetics of Russia, the starsti, enjoyed great renown, and innumerable crowds of people sought their counsel.