Vincent van Gogh said of the Mediterranean: “[It] has the colour of mackerel, changeable I mean. You don’t always know if it is green or violet, you can’t even say it’s blue, because the next moment the changing reflection has taken on a tint of rose or gray”.

His comment reveals how ephemeral colour is in the created world.

In our more regimented world we have fewer problems with colour and so are able to assign specific meaning to specific colours. Yet this has not always been so, and this fact affects how we read colour in Orthodox Icons.

You will find guides to the meaning and symbolism of colors in Orthodox Icons. I even give a couple of links at the bottom which give excellent summaries. Here, I will only write a few brief notes on why none of them should be considered completely definitive.

So, like the colours on a lake’s surface, the colours of Icons are transitory. Location, culture, the ravages of time, availability of natural dyes, expense, and even just plain ignorance (of symbolism in colours) all influence the colours used in Orthodox Icons. Nevertheless, the vagaries of colour can be overemphasized, and within Tradition there are guiding principles:

So, like the colours on a lake’s surface, the colours of Icons are transitory. Location, culture, the ravages of time, availability of natural dyes, expense, and even just plain ignorance (of symbolism in colours) all influence the colours used in Orthodox Icons. Nevertheless, the vagaries of colour can be overemphasized, and within Tradition there are guiding principles:

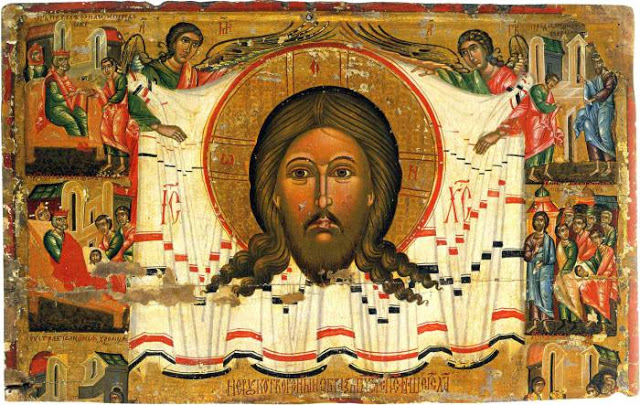

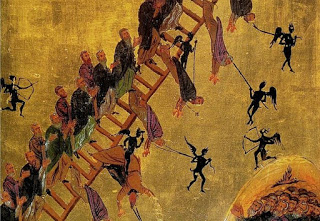

The overriding theme of colour in iconography, and in almost every religion, is the distinction between light and dark. This distinction is clear in the Scriptures, where the Divine is light and illuminating, and the absence of God is considered as darkness. This distinction is carried over into iconography and can be considered a fixed “rule”. In icons, therefore, graves, Hades, and the demons (e.g. the demons in the Ladder of Divine Ascent Icon) are always depicted as black, or as dark as possible with natural pigments.

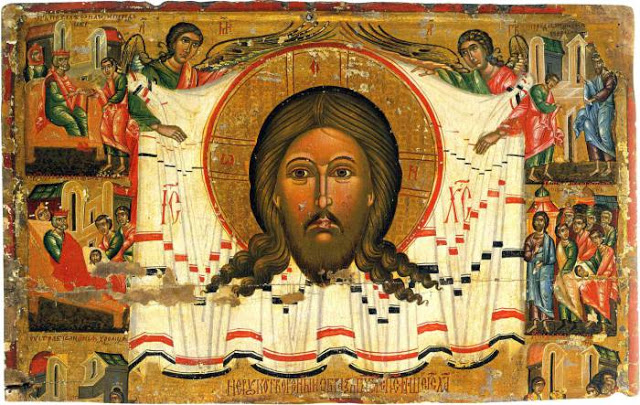

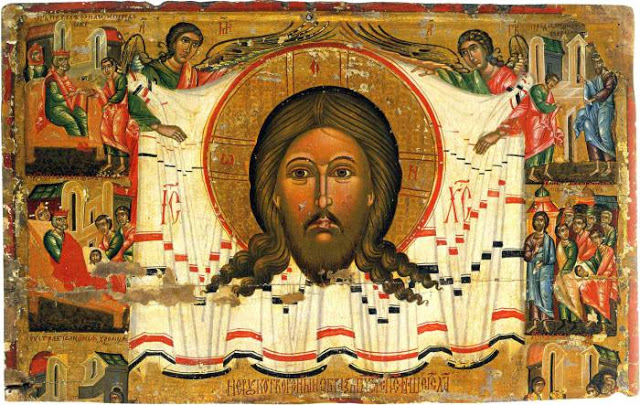

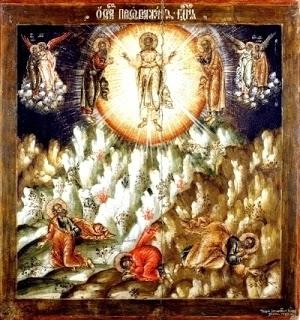

Consequently, Christ, His Angels, and the Saints are all depicted as light and illumined. To do this, it is not simply a case of using the colour white, as opposed to black. White is seen in numerous Divine revelations, and is always associated with purity, and it is this purity which affects its use in Icons. Quite simply, it is difficult to create a white that is white enough to represent the Heavenly Glory. It is much easier, and more impressive, to use natural light to reflect the Heavenly Light which is even more illuminating. This is primarily done with gold.

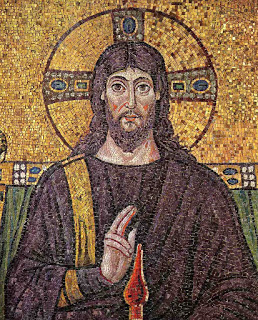

Traditionally applied to icons as a thin layer of gold leaf, this colour is used as the background for many Icons (I have never seen an icon with a white background), is often used for halos, and otherwise as a means of highlighting. In the Icon of Christ Enthroned on the right, gold is used to highlight the vestments Christ is wearing. The cloak itself is green, yet with the gold highlighting the whole image of Christ shimmers with light, as though the image itself were the source of light. This says exactly what we believe about Christ being the Light of the World. Using a certain colour to represent light means we must expect people to know this symbolism; on the other hand, the best Icons literally shine, and that is something which speaks to everyone.

The use of gold and other precious materials leads on to the next principle for using colour in Icons:

Beauty

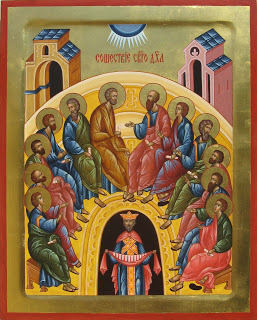

Icons must be beautiful. Whilst standards of beauty may change from place to place, the simple piety in trying to make Holy Images as beautiful as possible is constant. And so gold, as well as reflecting light, is also a precious metal – which must also influence its usage in Iconography of the Heavenly Realms. From Scripture, through the Traditions of the Church, and even today, gold is a symbol of royalty, the sun, and therefore of light. However, other colours can change meaning. This is why in the 6th century mosaic on the left, Christ is clothed in purple.

Tyrian purple was a colour made using dyes made from molluscs near Phoenicia. It was extremely expensive to produce and therefore only those of great wealth, usually nobility and sometimes only the Emperor, could afford it or were permitted to wear it. By 400 AD, less than half a kilo of cloth dyed with Tyrian purple, cost in excess of £12,000 in today’s money. Given its expense, and given its exclusive association with royalty, it becomes suddenly clear why the mosaics in Ravenna show Christ wearing purple.

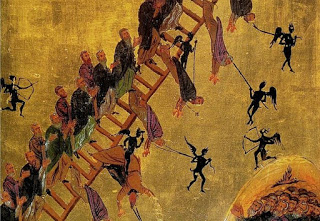

The Tradition of an Unorganized Religion

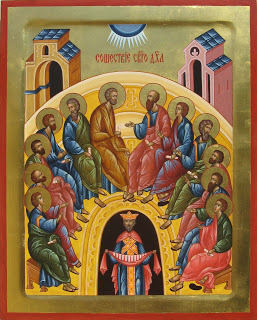

The Icons of Pentecost show us that the Church’s unity is not based upon being under a single, autocratic, hierarch. Orthodoxy is not an organized religion. The Faith remains unchanged, but people in different countries and continents differ. It is understandable, therefore, that from place to place, the expression of “the Faith” will differ, so that all may receive the same message in a way they can understand. What Tyrian purple was to a 6th century Byzantine might be what gold is for us today: a symbol of kingship. The important thing is that the kingship of Christ is communicated.

Iconography, like many aspects of Orthodox practice, took hundreds of years to develop. The Truth communicated was unchanging from the beginning, but its expression has taken time to become established. And, again, because Orthodoxy’s Vicar of Christ on Earth is not an incarnate human, but the invisible Holy Spirit, acting throughout the world, we must respect and accept differences in practice. We are called to unity, rather than uniformity. After all, even at Pentecost the Apostles are shown in robes of many colours.

With all that in mind, I offer these guides of on color in Orthodox Icons. They are still useful, as much of the symbolism is taken from Scriptures, which are themselves merely intuitive reflections on colour in nature (blue = sky/Heaven; white = clean/purity etc). Yet the traditions of colour in Orthodox Icons are rainbow-like in their diversity.

Vincent van Gogh said of the Mediterranean: “[It] has the colour of mackerel, changeable I mean. You don’t always know if it is green or violet, you can’t even say it’s blue, because the next moment the changing reflection has taken on a tint of rose or gray”.

Vincent van Gogh said of the Mediterranean: “[It] has the colour of mackerel, changeable I mean. You don’t always know if it is green or violet, you can’t even say it’s blue, because the next moment the changing reflection has taken on a tint of rose or gray”. So, like the colours on a lake’s surface, the colours of Icons are transitory. Location, culture, the ravages of time, availability of natural dyes, expense, and even just plain ignorance (of symbolism in colours) all influence the colours used in Orthodox Icons. Nevertheless, the vagaries of colour can be overemphasized, and within Tradition there are guiding principles:

So, like the colours on a lake’s surface, the colours of Icons are transitory. Location, culture, the ravages of time, availability of natural dyes, expense, and even just plain ignorance (of symbolism in colours) all influence the colours used in Orthodox Icons. Nevertheless, the vagaries of colour can be overemphasized, and within Tradition there are guiding principles: The overriding theme of colour in iconography, and in almost every religion, is the distinction between light and dark. This distinction is clear in the Scriptures, where the Divine is light and illuminating, and the absence of God is considered as darkness. This distinction is carried over into iconography and can be considered a fixed “rule”. In icons, therefore, graves, Hades, and the demons (e.g. the demons in the Ladder of Divine Ascent Icon) are always depicted as black, or as dark as possible with natural pigments.

The overriding theme of colour in iconography, and in almost every religion, is the distinction between light and dark. This distinction is clear in the Scriptures, where the Divine is light and illuminating, and the absence of God is considered as darkness. This distinction is carried over into iconography and can be considered a fixed “rule”. In icons, therefore, graves, Hades, and the demons (e.g. the demons in the Ladder of Divine Ascent Icon) are always depicted as black, or as dark as possible with natural pigments.

Iconography, like many aspects of Orthodox practice, took hundreds of years to develop. The Truth communicated was unchanging from the beginning, but its expression has taken time to become established. And, again, because Orthodoxy’s Vicar of Christ on Earth is not an incarnate human, but the invisible Holy Spirit, acting throughout the world, we must respect and accept differences in practice. We are called to unity, rather than uniformity. After all, even at Pentecost the Apostles are shown in robes of many colours.

Iconography, like many aspects of Orthodox practice, took hundreds of years to develop. The Truth communicated was unchanging from the beginning, but its expression has taken time to become established. And, again, because Orthodoxy’s Vicar of Christ on Earth is not an incarnate human, but the invisible Holy Spirit, acting throughout the world, we must respect and accept differences in practice. We are called to unity, rather than uniformity. After all, even at Pentecost the Apostles are shown in robes of many colours.