The holiday of the Ascension was established in the Church calendar around the 4th century. The great Fathers of the Church – St. Gregory of Nissa and St. John Chrysostom – were the authors of the very first homilies on Ascension, while Blessed Augustine mentions the widespread celebration of this day in his works.

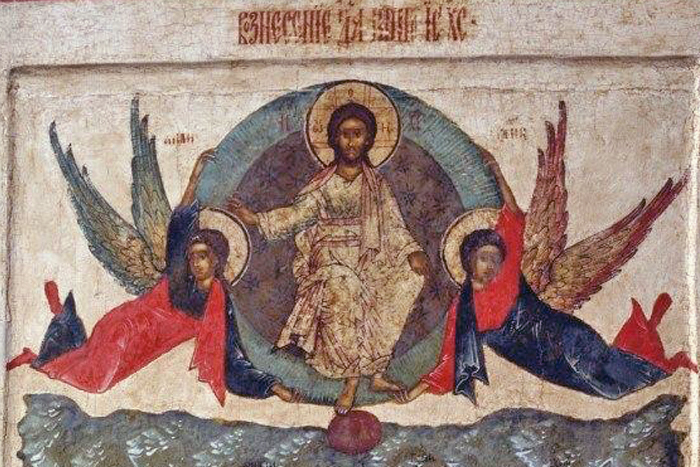

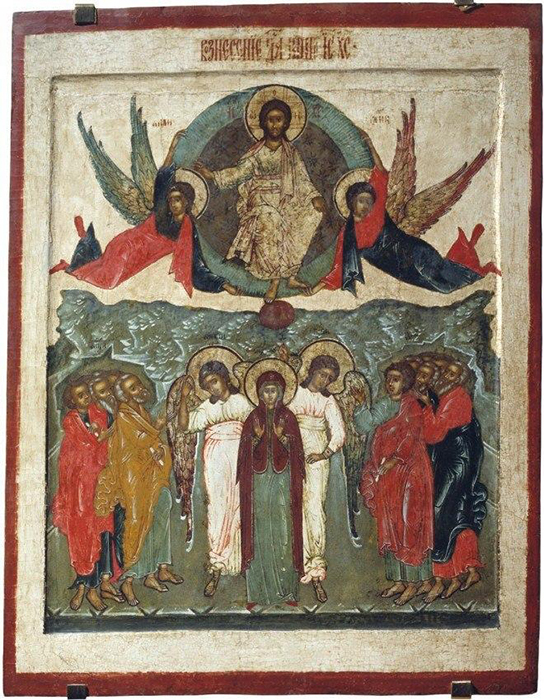

The iconography of the Ascension depicts the Lord Jesus Christ sitting on the Throne of glory in bright robes, white or gold. The image of the Savior is enclosed in a mandorla, i.e. circles representing the celestial sphere, which is also usually filled with golden rays that shine in all directions. The image of Christ is like the sun. Angels hold the celestial sphere with the image of the Savior on it.

The glory and majesty of the ascending Christ was most vividly expressed in fresco painting. This scene, as well as Christ the Pantocrator or the Descent of the Holy Spirit, is used in paintings that are usually concentrated in the dome of the temple, and often take up the walls of the “neck” or “drum” under the dome. There are also examples where the Ascension is painted in the conch above the altar of the temple. The Savior is portrayed in the middle of the dome, as if inscribed in the celestial vault, which is created by the very architecture of the temple: the spherical, rounded surface of the dome resembles the celestial vault, both in its appearance and symbolic meaning that the Church gives it. The drum most often depicts angels supporting the dome sphere with their hands. In Russia, the composition of the Ascension appears in the dome paintings of the 9th-12th centuries, e.g. in the Transfiguration Cathedral of the Mirozhsky Monastery in Pskov, the Church of St. George in Staraya Ladoga and the Church of the Savior on Nereditsa.

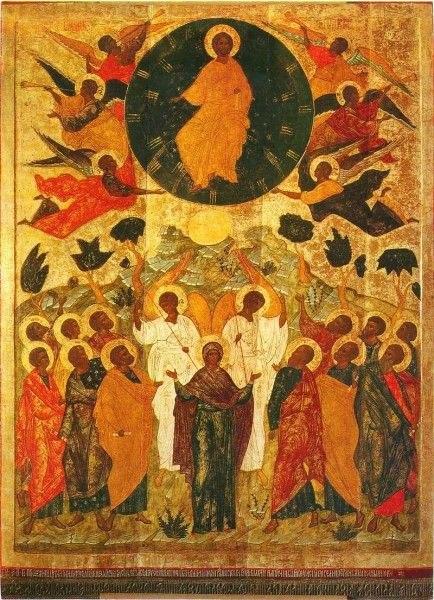

The Ascension icon has appeared in the Russian high iconostasis since the mid-14th century. Over time, the well-known iconography has developed: twelve apostles with the Mother of God in the center. The only thing that varies is the number of angels. For example, a Novgorod icon from 1542 depicts six angels.

The composition of the icon is divided into two semantic parts. The upper part shows the Savior. Both His hands are raised for blessing. The mountain with the Mother of God in the Oranta position with her hands lifted up in prayer, angels and apostles in the background is at the bottom of the icon. The mountain on an Ascension icon shows the place where the depicted event occurred, but it also symbolizes the steps of spiritual ascent.

One can notice something special on some icons: there is a footprint of the Lord Jesus Christ on the top of the Mount of Olives, from where He ascends to heaven. It is the actual footprint of Christ on the stone that is shown to all the pilgrims who arrive in Jerusalem (read more The Holy Objects of the Mount of Olives).

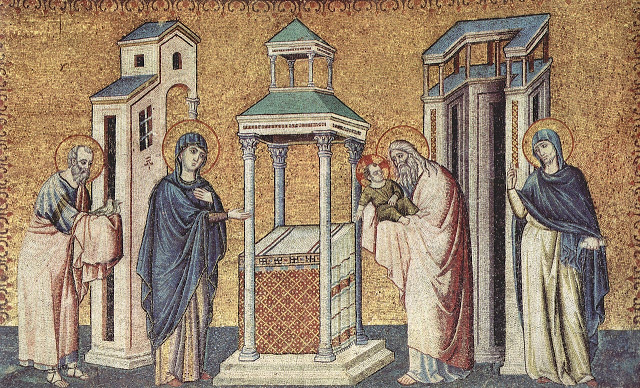

While many holiday icons illustrate the events remembered on that day, we find one and the same phenomenon in both Ascension and Pentecost icons: the divine service of Ascension confirms the presence of the Mother of God among the disciples at the time of Christ’s Ascension, and the icon of this feast shows her in the center of the composition, despite the fact that the New Testament texts do not mention it.

The Incarnation was not only the work of the Father, His Power and His Spirit, but also resulted from the will and faith of the Virgin Mary. The humanity represented by the Virgin gave its consent for the incarnation of the Savior, for the Word becoming flesh. Being the prerequisite for human salvation, she is depicted on the icon of the Ascension as the direct evidence of His Incarnation.

The presence of the Apostle Paul also contradicts historical data (he was called Saul on the day of Ascension and had nothing to do with Christianity yet). The Evangelists Luke and Mark of the Seventy, though they indeed were among those present, did not belong to the circle of the twelve apostles proper; nevertheless, they are portrayed among them. The Gospels which the Evangelists hold in their hands on the icon are not yet written.

One peculiar feature is that the apostles do not have halos on most icons. Only the Savior, the Angels at the top of the icon, the Mother of God and the two Angels at the bottom – “men in white robes” as they are described in the Book of Acts – have halos. However, all the apostles have halos on the icons of later time, as well as on the aforementioned Novgorod icon of 1542.

The absence of the halos of the apostles on the icon of the Ascension, however, is best justified theologically as evidence that the grace of the Holy Spirit, the Comforter, has not yet descended upon the disciples of Christ. He appeared on the day of Pentecost, as promised by the Savior.

Despite the fact that the icon does not illustrate the historical event of the Ascension as described in the sacred texts, the numerous images of the Ascension convey the main pinnacle of the holiday — the triumph of Christ who lifted up the human body above the angelic ranks, elevating human nature from death to endless life in heaven, where He sits at the right hand of God the Father.