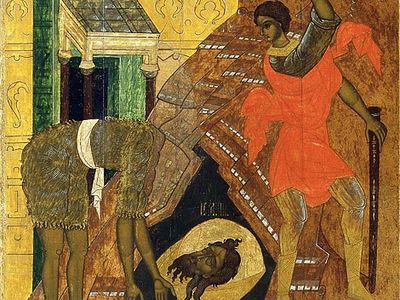

Holy Scripture tells us that after St. John the Baptist was beheaded, the impious Herodias forbade the prophet’s head to be buried together with his body. Instead, she desecrated the honorable head and buried it near her palace. The saint’s disciples had secretly taken their teacher’s body and buried it. The wife of King Herod’s steward knew where Herodias had buried St. John’s head, and she decided to rebury it on the Mount of Olives, on one of Herod’s estates.

Holy Scripture tells us that after St. John the Baptist was beheaded, the impious Herodias forbade the prophet’s head to be buried together with his body. Instead, she desecrated the honorable head and buried it near her palace. The saint’s disciples had secretly taken their teacher’s body and buried it. The wife of King Herod’s steward knew where Herodias had buried St. John’s head, and she decided to rebury it on the Mount of Olives, on one of Herod’s estates.

When word reached the royal palace about Jesus’ preaching and miracles, Herod went with his wife Herodias to see if John the Baptist’s head was still in the place they had left it. When they did not find it there, they began to think that Jesus Christ was John the Baptist resurrected. The Gospels witness to this error of theirs (cf. Mt. 14:2).

Jerusalem. The First Uncovering of the Head of St. John the Baptist

May years later, during the reign of Equal-to-the-Apostles Emperor Constantine, his mother, St. Helen, began restoring the holy places of Jerusalem. Many pilgrims streamed into Jerusalem, amongst whom where two monks from the East, wishing to venerate the Lord’s Honorable Cross and Holy Sepulcher. St. John the Baptist entrusted these two pilgrims to discover his head. We only know that he appeared to them in a dream; and that after finding the head in the place he showed them, they decided to return to their native city. However, God’s will determined otherwise. Along the road, they met a poor potter from the Syrian town of Emesa (modern-day Homs), whose poverty had forced him to seek work in a neighboring country. Having found a co-traveler, the monks either out of laziness or carelessness entrusted him with carrying the sack containing the relic. As he was carrying it, St. John the Baptist appeared to him and told him to forget the careless monks and run away from them, taking the sack they had given him.

For the sake of the precious head of St. John the Baptist, the Lord blessed the potter’s house with an abundance of goods. The potter lived his whole life remembering his Benefactor, giving alms generously. Not long before his death he gave the precious head to his sister, commanding her to pass it on to other God-fearing, virtuous Christians.

The saint’s head was passed along from one person to the next, and came into the hands of one Hieromonk Eustacius, who sided with the Arian heresy. Sick people who came to him received healing, not knowing that it was due not to Eustacius’s false piety, but to the grace coming from the hidden head. Soon Eustacius’s ruse was exposed, and he was banished from Emesa. A monastery grew around the cave where the hieromonk had lived and in which the head of St. John the Baptist was buried.

Emesa and Constantinople. The Second and Third Finding of the Precious Head.

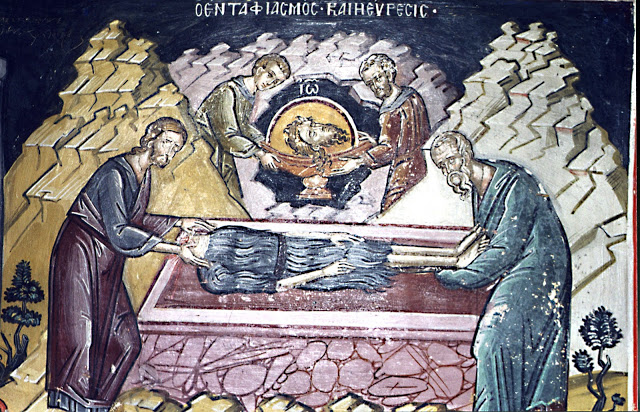

After many years, the head of St. John the Baptist was uncovered a second time. We know about this from a description by Archimandrite Marcellus of the monastery in Emesa, as well as from the life of St. Matrona (†492, commemorated November 9/22), written by St. Simeon Metraphrastes. According to the first description, the head was discovered on February 18, 452. A week later, Bishop Uranius of Emesa established its veneration, and on February 26 of the same year, it was translated to the newly-built church dedicated to St. John. These events are celebrated on February 24/March 8, along with the commemoration of the First Finding of the Precious Head.

After some time, the head of St. John the Forerunner was translated to Constantinople, where it was located up to the time of the iconoclasts. Pious Christians who left Constantinople secretly took the head of St. John the Baptist with them, and then hid it in Comana (near Sukhumi, Abkhazia), the city where St. John Chrysostom died in exile (407). After the Seventh Ecumenical Council (787), which reestablished the veneration of icons, the head of St. John the Baptist was returned to the Byzantine capital in around the year 850. The Church commemorates this event on May 25/June 7 as the Third Finding of the Precious Head of St. John the Baptist.

The Fourth Crusade and travel to the West

Ordinarily, the Orthodox history of the finding of the head of St. John the Baptist ends with the Third Finding. This is due to the fact that its later history is bound up with the Catholic West. If we look at the Lives of the Saints written in the Menaon of St. Dimitry of Rostov, we find a citation in small print, often overlooked by readers, at the end of story of the Finding of the Forerunner’s Head. However, after unexpectedly discovering the head of St. John the Baptist in France and then returning home to Russia, this citation became a real revelation for us. It is this next “finding” of the head of St. John the Baptist that we would like to write about below.

Thus, we read in this citation that after 850, part of the head of St. John the Baptist came to be located in the Podromos Monastery in Petra, and the other part in the Forerunner Monastery of the Studion. The upper part of the head was seen there by the pilgrim Antony in 1200. Nevertheless, in 1204 it was taken by crusaders to Amiens in northern France. Besides that, the citation shows three other locations of pieces of the head: the Athonite monastery Dionysiou, the Ugro-Wallachian monastery of Kalua, and the Church of Pope Sylvester in Rome, where a piece was taken from Amiens.

The history of the Baptist’s head’s appearance in France differs little from the history of many other great Christian relics.

On April 13, 1204, during the Fourth Crusade, an army of knights from Western Europe seized the capital of the Roman Empire—Constantinople. The city was looted and decimated.

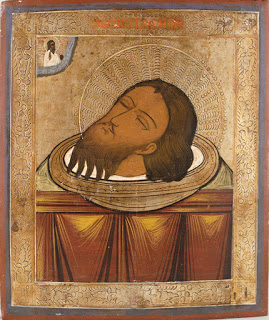

As Western tradition has it, Canon Wallon de Sarton from Picquigny found a case in one of the ruined palaces that contained a silver plate. On it, under a glass covering, were the hidden remains of a human face, missing only the lower jaw. Over the left brow could be seen a small perforation, most likely made by a knife strike.

On the plate the canon discovered an inscription in Greek confirming that it contained the relics of St. John the Forerunner. Furthermore, the perforation over the brow corresponded with the event recorded by St. Jerome. According to his testimony, Heriodias in a fit of rage struck a blow with a knife to the saint’s severed head.

Wallon de Sarton decided to take the head of the Holy Forerunner to Picardy, in northern France.

On December 17, 1206, on the third Sunday of the Nativity fast, the Catholic bishop of the town of Amiens, Richard de Gerberoy, solemnly met the relics of St. John the Baptist at the town gates. Probably the bishop was sure of the relic’s authenticity—something easier to ascertain in those days, as they say, “by fresh tracks”. The veneration of the head of St. John the Baptist in Amiens and all of Picardy begins from that time.

In 1220, the bishop of Amiens placed the cornerstone in the foundation of a new cathedral, which after many reconstructions would later become the most magnificent Gothic edifice in Europe. The facial section of the head of the St. John the Baptist, the city’s major holy shrine, was transferred to this new cathedral.

Eventually, Amiens became a place of pilgrimage not only for simple Christians, but also for French kings, princes and princesses. The first King to come and venerate the head in 1264 was Louis IX, called “the Holy”. After him came his son, Phillip III the Brave, then Charles VI, and Charles VII, who donated large sums for the relic’s adornment.

In 1604, Pope Clement VIII of Rome, wishing to enrich the Church of the Forerunner in Rome (Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano), requested a piece of St. John’s relics from the canon of Amiens.

Saving of the head from the outrages of the French revolution

After the revolution in 1789, inventory was made of all Church property and relics were confiscated.

The reliquary containing the head of the Holy Forerunner remained in the cathedral until November, 1793, when it was demanded by representatives of the Convention. They stripped from it everything of material value, and ordered that the relics be taken to the cemetery. However, the revolutionary command was not fulfilled. After they left the city, the city’s mayor, Louis-Alexandre Lescouve, secretly and under fear of death returned to the reliquary and took the relics to his own home. Thus was the sacred shrine preserved. Several years later, the former mayor gave the relic to Abbot Lejeune. Once the revolutionary persecutions had ended, the head of St. John the Baptist was returned to the cathedral in Amiens in 1816, where it remains to this day.

At the end of the nineteenth century, historical science, not without the participation of ecclesiastical figures, determined that there had been many instances of false relics during the Middle Ages. In an atmosphere of general mistrust, veneration of the Amiens shrine eventually began to wane.

The head of St. John the Baptist today

In the mid-twentieth century, specifically in 1958, there was a spark of renewed interest in the relics of St. John the Baptist. The rector of the Amiens cathedral reported to the ecclesiastical authorities that in eastern France, in Verdun, was what was presumed to be the lower jaw of St. John the Baptist. He wanted to rejoin the two parts. With the blessing of the bishop of Amiens, a commission of qualified medical experts was formed.

The relics were investigated for several months, in two stages—the first in Amiens, the second in Paris. After the work was completed, the commission’s findings were gathered into a document, signed by the members. In the first chapter of the document, which covers the research performed in Amiens, the following conclusions were made:

- Comparison of the subject called “of Verdun” with the subject from Amiens disclosed their anatomical differences, confirming without a doubt that they are of differing origins.

- From the chronological point of view, the subject called “of Verdun” is not as ancient as the Amiens subject. It is similar in form and weight to “bones of the Middle Ages”.

- The facial part, called the head of St. John the Baptist from Amiens, is a very ancient object—more ancient than “bones of the Middle Ages”. On the other hand, it is younger than human bones of the Mesolithic era—which allows us to date it at between 500 BC and 1000 AD.

- The man’s age could not be determined precisely due to the absence of teeth. But based upon the fact that the alveolar [tooth] sockets are fully developed and are slightly worn at the edges, it can be supposed that the man was an adult (between 25 and 40 years old).

- General characteristics of the head in the form of inadequate elements can be determined, but with great permissible variation. The facial type is Caucasoid (that is, not Negroid or Mongoloid). The small measurements of the subject from Amiens and the development of the lower eye sockets lead to the supposition that it could correspond to a racial type called “Mediterranean” (a type to which modern Bedouins belong).

Here ends the modern chronicle of the head of St. John the Baptist. Unfortunately, few of the faithful have recourse to the help of such a lamp of grace as the precious head of St. John the Baptist, “the first among martyrs in grace”. Many Orthodox Christians come to France, but not all of them know how many holy relics there are still on French soil despite the outrages committed against them during the French Revolution and subsequent forgetfulness of France’s Christian past.

Joyfully, during recent years more and more Orthodox pilgrims are travelling to Amiens. Now, with the help of the Pilgrimage Center of the diocese of Korsun (of the Moscow Patriarchate, based in Paris) Orthodox molebens and even Divine Liturgies are now being served before the head of St. John the Baptist.

Dear Saint John the Baptist thank you for your prayers please pray to God for us.

Thank you for this description. I am totally confused about it, though. The first time I went to Istanbul, I found out that their claim is that his head is the one in Top Kapi museum. I cannot tell you how much I’ve cried in there, thinking he is not honored. After a while, I’ve found out about the claims that his head is in the Holy Mountain and I’ve felt relief. And now… in France?