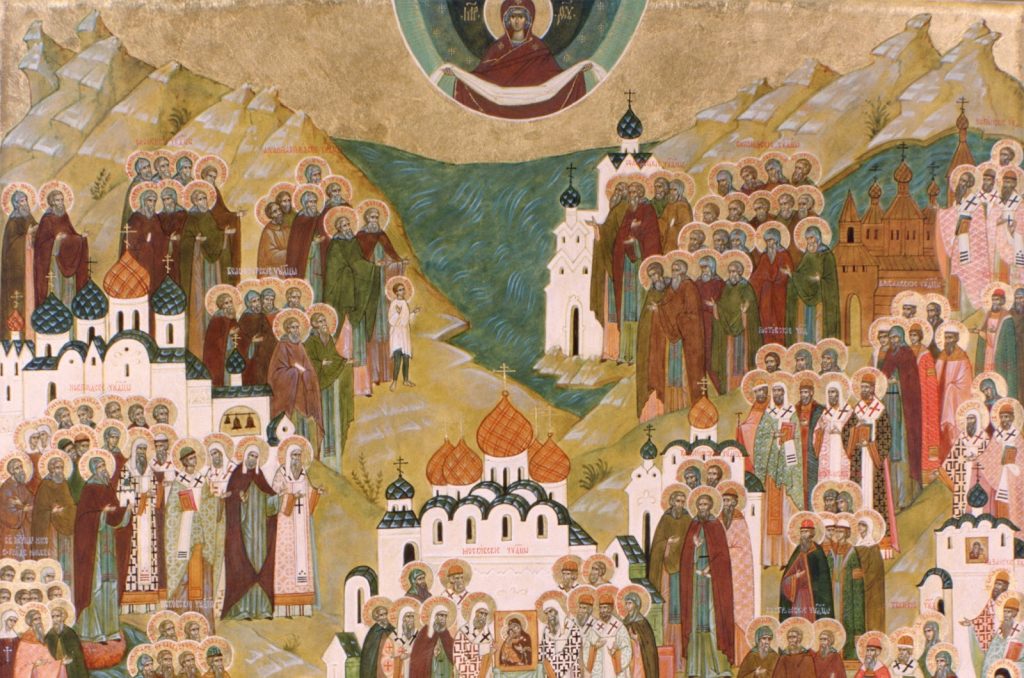

Icon painting is based on the canon, that is, the rule. On the other hand, we have to deal with lots of issues all the time. This is especially true when we paint icons of newly-canonized saints, i.e., martyrs, the righteous ones, and the blesseds of the 20th century. There is no established canon yet. However, we have their photos at our disposal, and they might ostensibly help us to paint the saints’ icons. If only it worked that way.

The icon of St. Matrona of Moscow in St. Thomas Church where the Rev. Daniel Sysoev was the parish priest.

According to Father Daniel, we depict saints in their transformed state, that is, as they are in Heaven. Therefore, they cannot have the ailments that they used to have while alive.

Saint Matrona of Moscow was canonized first as a local saint in 1999, and then as the universally venerated saint in 2004. Little time passed between those two events but it had already become an established tradition to portray St. Matrona blind, that is, true to life. That image is familiar and approved by the faithful.

At the same time, an icon is not a portrait. The Church doctrine regarding veneration of icons claims that there is the transformed human being who is a partaker of the Divine life whom we can contact through the image. That is why saints are usually painted without emphasizing their physical defects too much. Let’s recall icons of Saint Seraphim of Sarov: he is depicted as a slightly but not entirely bow-backed old man.

Therefore, there have been two ways of painting St. Matrona: with closed eyes and with open eyes. When we paint the icon, we show our initial draft to the priest who ordered it and ask him for his blessing. Either the parish priest of the church for which we paint the icon or the spiritual father of the person who ordered the icon has the final say in this matter. Thus, we icon painters avoid unauthorized activity. I believe that parishioners shouldn’t be wary of “incorrect” icons.