Where do Orthodox Monks and Nuns Come From?

Orthodox monks and nuns come from all walks and manner of life. In former times the greater number were of peasant stock, but at the same time many a great name lay hidden under the humble black habit and the new Christian name received at tonsure. Certainly there were to be found many unlettered and uncultured monks, because the cloister was and is open to all, regardless of social rank or education. But if one reads the daily offices and grasps their scriptural and theological wealth, and if one hears the readings from the Holy Fathers–all of which are the monk’s daily fare, one begins to think twice about the intellectual superiority of their critics. It must not be forgotten that it was the monks who translated these services and writings into their native tongues, a continuing labor in which nuns also take part. There are also spiritual writings that are unique to each nation, the beauty of which is unsurpassed in secular compositions-but which are little known outside the cloister. In monasteries were painted world famous icons and from them came exquisite embroideries and priceless illuminated manuscripts. All were written, painted and worked anonymously for the greater glory of God, reflecting that humility which is the keynote of all Christian monasticism.

The Monastic Daily Life

The devotional pattern of the monastic day is based upon the words of the Psalmist:” Seven times a day do I praise Thee because of Thy righteous judgments.” (Ps. 1 19:64)

Consequently, there are seven praises (Lauds) in each 24-hour cycle. These are arranged as follows:

1) Midnight Office;

2) Matins together with

3) First Hour;

4) Third and Sixth Hours;

5) Ninth Hour;

6) Vespers and

7) Compline.

They are called praises or lauds because they mirror the Saviour’s redemptive work for mankind, as well as various events in His divine life and in the life of the Holy Apostles and the Church.

1) The Midnight Office is said at or after midnight and is a reminder of the Resurrection which took place “early in the morning,” and also of the Second Coming, the hour of which no man knos (Mark 13:33, 35). It likewise recalls the parable of the bridegroom who came at midnight and the five foolish virgins whose lamps had gone out: “Watch therefore, for ye know neither the day nor the hour wherein the Son o f man cometh” (Matt. 25:13).

2) This is followed by Matins which ends at dawn, reflecting the dawn of our salvation,

3) The First Hour is then read, praising the beginning of the new day in which we join our hymns to those of the angels, together bringing them before God.

4) The Third and Sixth Hours are read before the Divine Liturgy, In the Third Hour the death of Cur Lord was plotted; also at this hour the Holy Spirit descended upon the Apostles. The Sixth Hour commemorates the Passion and Crucifixion of our Lord. If there is no Liturgy, the Typica is read which gives a sketch of the Liturgy.

5 & 6) In the evening the Ninth Hour is read. Its prayers recall the hour in which the Lord laid down His life for the redemption of the world. Without pause there begins the service of Vespers which tells of the creation, of God’s love for the world, of man’s fall into sin, his expulsion from paradise and of the Redeemer’s coming upon earth,

7) Before retiring, Compline is sung, bringing thanks for the coming of night with its rest and the remembrance of death for which we must always be prepared. This is followed by evening prayers.

Within the framework of this daily cycle flows the monk’s life so that it may be filled with holiness, with grace from above, and hope of eternal blessedness, whatever his task–be it manual or intellectual work or the practice of hesychasm towards which all monastic life is directed.

The Stages of Monastic Life

The person, man or woman, who enters monastic life, tries to leave his or her old self behind, with all the old joys and sorrows, virtues and sins, and starts a new life, seeking to find a new relationship to all things and people in Christ, to Whom he vows his life. The taking of the monastic vow and habit are but a repetition and amplification of the baptismal vows.

At first there were no stages along the monastic path; there were no postulants or novices but simply monks. Today, however, monastics generally progress from one stage to another: the postulant looks forward to becoming a novice, the novice to receiving the habit and going on to full profession-which may take years or which he may never reach. There is no prescribed time period for each stage, but at least three years must elapse before full profession. The intermittent stages may even be dispensed with in certain cases, in communist ruled territories, for example, where the normal flow of monastic life is impossible. There is also no obligation to advance from one stage to the next; should a novice not feel ready or not wish to progress for reasons of humility, he/she is free to remain in the monastery as he is. Monks who become priests are called hieromonks; this does not affect their monastic status.

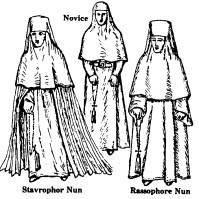

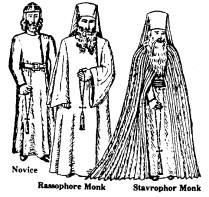

1) Novice. One begins as a postulant who may be permitted, after three months or so, to wear a portion of the habit (tunic and belt), which is regarded as a tacit expression of his/her determination to abide in the monastic life of asceticism, subject to the approval of the abbot (abbess). In becoming a novice, the aspirant receives in addition to the tunic (podriasnik) and belt, the monastic head covering, called “skoufos” for men and “apostolnik” for women.

2) Rassophore. When the superior thinks fit, the novice may ask the bishop to receive the riassa or habit, an over-garment with wide sleeves and reaching to the ankles, and also the monastic head covering with veil (in Russian–klobuk; in Greek–kamelos). This portion of the habit is given with the appropriate rite in church by a hieromonk. The new monk or nun takes no vows at this time, but should a rassophore leave the monastery and wish to marry, he or she must receive written permission of the bishop, without which he would incur excommunication.

3) Stavropbor, from the Greek “stavros” (cross) and “phoros” (to wear), so called because the monk/nun wears a wooden cross on the chest tied under the habit to a paramanydas or paraman which is worn on the back. The paraman is a small square piece of fabric embroidered with representations of the Cross, spear, reed, sponge, the pillar of scourging, Adam’s skull and the cock which crowed at the time of Peter’s denial. At the same time he/she receives the mandyas or mantia, a flowing cloak without hood, which reaches to the ground in long narrow pleats, and which is worn only in church. This profession takes place according to an impressive and solemn rite; the vows are made before a hieromonk. The profession is made publicly in church and the vows of Stability, Obedience, Poverty and Chastity are given by the candidate before he/she receives the tonsure, the paraman and mantia which are new added to the habit. The officiating priest bestows a new name upon the monk in recognition of the beginning of his new life. The monk does not choose this name himself but accepts it as his first act of obedience.

The Orthodox attitude towards monasticism is best summed up in the collect of the Prodigal Son with which the ceremony of profession opens:

Make haste to open Thy fatherly arms

Unto me who have wasted my life like the prodigal.

Despise not a heart now grown poor

O Saviour Who hast before Thine eyes

The boundless riches of Thy mercies.

For unto Thee, O Lord, in compunction do I cry:

O Father, I have sinned against heaven and before Thee…

(Here the monk is a penitent.)

and the verse which is sung during the clothing:

My soul shall rejoice in the Lord:

for He hath put on me the garment of salvation;

And with the tunic of gladness hath He clothed me.

He hath put upon me a crown as upon a bride groom,

And as a bride hath he adorned me…

(Here the monk is the betrothed of God.)

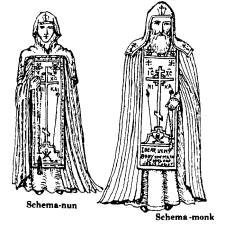

4) Megaloschema, from the Greek “megas” (great) and “schema” (habit), or in Russian, “skhmnik”. The difference between the Stavrophor and the Megaloschemos lies inthe degree of asceticism which, for the latter, is very strict and not something of which everyone is capable. In addition to the habit of the Stavrophor, the Megaloschemos wears the analovos which is rather like the Western scapular in shape, although there is no symbolic or historical connection between them. The analovos is embroidered with the cross which the monk is to take up daily in following Christ. The same representation figures on the koukoulion, a thimble-shaped kamelos. These are given according to a rite, similar to that of stavrophor, in which the original vows are repeated with yet greater solemnity. These two rites are also referred to respectively as the receiving of the Little and the Great Habits.

The distinctive color of the monastic raiment is black which symbolizes that the second Baptism is more laborious than the first whose symbolic color is white, for the second is a baptism of repentance, which will end only with the end of this present deceitful life.