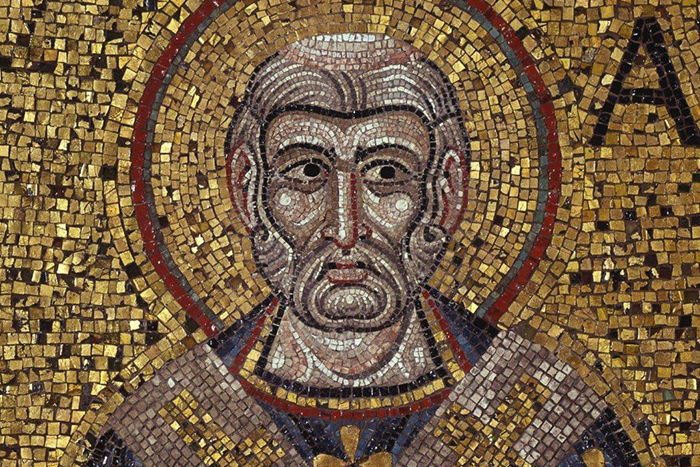

Blessed Augustine is known not only in the West, but also in the Orthodox East. We honor the memory of this saint, read his works, and study his heritage. His struggle against the heresy of Pelagianism was highly appreciated by the entire Catholic Church, having received the approval of the Third Ecumenical Council (†431). However, many Orthodox Christians are suspicious not only of the teaching of the Blessed Augustine about the fate of unbaptized infants, but also, which is no less important, of the Augustine theology of the Holy Trinity. After all, it was the doctrine of this saint that laid the foundation for the Roman Catholic dogma Filioque (“and the Son”), which became one of the stumbling blocks to the unity of Christians in the East and West.

What possible theological mistakes of the Bishop of Hippo led the Western Church to accept this controversial dogma? In 393, there was a council of African bishops. The Fathers asked Blessed Augustine to tell them about the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, which had been adopted shortly before that at the Second Ecumenical Council in 381 and which had just begun to spread to all local churches. Augustine would later redraft his speech and spread it, but for the rest of his life he probably did not realize that he had made three important mistakes.

Mistake #1. In “De Fide et Symbolo” (Augustine. De Fide et Symbolo, 19.), the Bishop of Hippo makes the following statement: “As for the Holy Spirit, however, there has not yet been a discussion on the part of scholars and eminent researchers of Scripture that is complete and thorough enough to enable us to gain a reasonable understanding of what also constitutes His peculiarity.” However, this statement is erroneous, because the peculiarity of the Holy Spirit was revealed by the Fathers of the Second Ecumenical Council and it is nothing but the image of the existence of the Spirit, His hypostatic property, namely the descent from the Father. The Father is not born, he has a being in himself, the Son receives his being from the Father through birth and the Holy Spirit from the Father through descent. Augustine did not understand this, nor did those early medieval Western theologians, who mainly relied on the work of St. Augustine, deeming him superior to other Fathers.

Mistake #2. St. Augustine’s next mistake was to identify the Holy Spirit with the energy of Deity (θεοτης) and to affirm that this energy of Deity is love between the Father and the Son. It appears that Aurelius Augustine did not fully understand the theology of the great Cappadocians. For they categorically dismissed the very thought that the Holy Spirit could be reduced to the common energies of the Father and the Son, called θεοτης and love, for these energies are neither nature nor Hypostasis, while the Holy Spirit is the full Hypostasis. The Holy Spirit has the same nature as the Father and the Son, but He is a separate Person with a unique property that only He has, namely the eternal descent from the Father as the Cause. It is the fundamental Orthodox theology of the Trinity. For Augustine, however, the Holy Spirit is the common love of the Father and the Son, and hence He exists for the reason of both. Augustine mixes birth and descent, which inevitably leads him to the Filioque.

Mistake #3. Augustine’s third mistake, which led his Trinity theology to Filioque, is not about the features of his Trinity theology, but about his theological method itself. Following this method, Augustine comes to the conclusion that not only individuals, but also the Church itself, over time, gains a better understanding of dogmata. Augustine states that the Church still awaits a comprehensive discussion about the Holy Spirit. Western Scholastic thinkers took this conviction of the great Augustine seriously, which became a favorable ground for them in their efforts to improve and develop the Trinitarian theology of the Fathers.

When Charlemagne was crowned as Emperor of the Western Roman Empire by the Pope in 800, the teaching of Filioque had not yet been accepted by the Roman Church, but was widespread in France. The Franks wanted to prove to the world that they, and not the Eastern Romans, were the heirs of the ancient Romans. Their main argument was that they followed the doctrine of Filioque, orthodox in their view, as opposed to the inhabitants of the Eastern Empire. Consequently, the Eastern emperors, without accepting Augustine’s teaching on Filioque, were not entirely Orthodox and therefore were not legitimate.

Perhaps if Augustine had known and understood better the doctrine of the Trinity of such great Church Fathers as Saints Gregory the Theologian, Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, he would have changed his point of view and not made these mistakes. However, history does not have the subjunctive mood and we only have to testify and defend the faith of the Fathers, study their creations, and engage in their spirit, so that we can give an account of our trust and give it with “meekness and fear” (1 Peter 3:15).