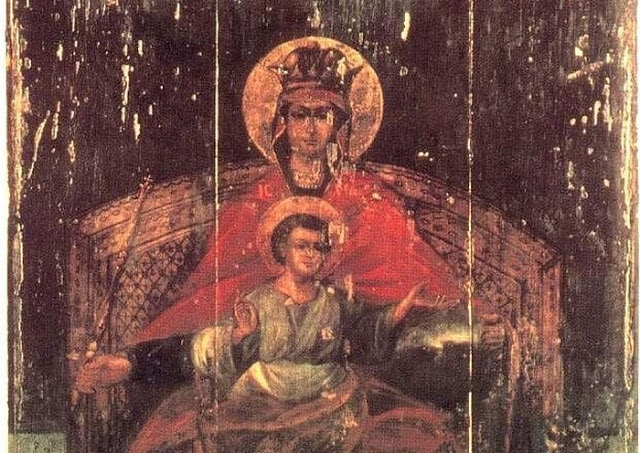

The Great Feasts serve to tell us the story of the Incarnation, which has its climax in the center of the year with the celebration of the “Feast of Feasts” – Pascha (Easter). It is therefore fitting that the first Great Feast of the Church year, which begins in September (on September,14), is that of the Nativity of the Theotokos.

The early life of Mary, the Mother of God, up to the occasion of the Annunciation is described in the ancient Protoevangelium of James. Hymnography and iconography for the feasts celebrating Mary’s conception, birth, and dedication to the Temple as a child, all borrow from this early (2nd century) account.

The Mother of God’s birth was miraculous, not because she was born without original sin, nor because she was born of a virgin, but instead because she was born of a man and his barren wife: Joachim and Anna.

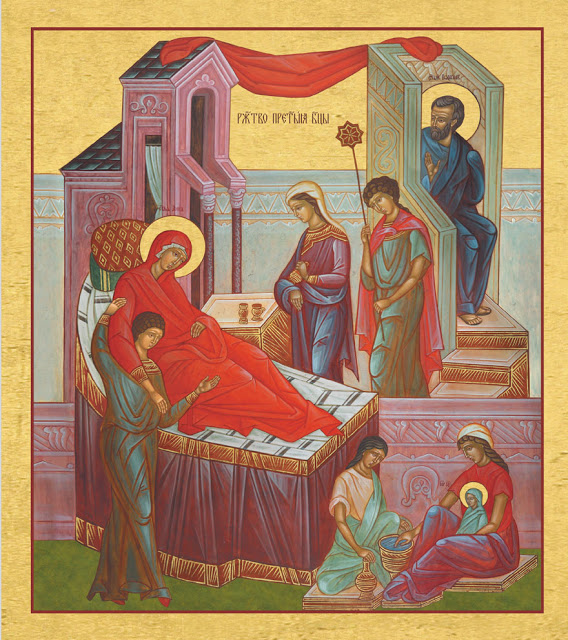

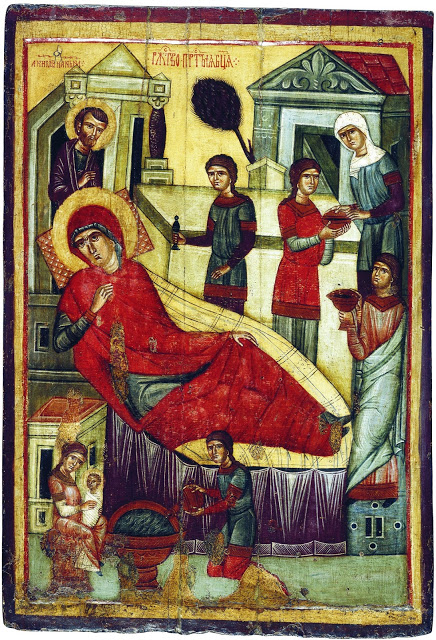

The icon of the feast is a more-or-less faithful imaging of the protoevangelium, with the composition echoing the Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ which Mary’s birth prepares the way for. Anna is reclining in a bed, in a similar way to how Mary herself reclines on icons of Christ’s Nativity. Below Anna, the infant Mary is being bathed by midwives, just as the infant Christ is washed by Salome on the icon of His own birth. Likewise, just as Joseph is shown removed from the main scene of the birth in Nativity icons, Mary’s father Joachim is also shown apart from the scene in icons of the Theotokos’ birth.

As for the differences, the main one is that the surroundings. Whereas Christ’s birth is shown to be in a cave, in the wilderness, the Mother of God’s birth is shown within the city walls, amid what appears to be a beautifully decorated house, because Joachim was “a man rich exceedingly”. Instead of a cave, Mary is inside Anna’s bed-chamber, which according to the protoevangelium was made into a sanctuary until the time Mary entered the Temple. Whereas Mary and the Christ-child are attended by angels in their relative solitude, around Anna is a hive of activity: the “undefiled daughters of the Hebrews” whom Anna brought into the bed-chamber to attend to her. A table by Anna shows the feast which Joachim prepared on Mary’s first birthday, to which were invited the scribes, priests and elders of Israel.

Other details which may be present are separate details of Anna, Joachim and the infant Mary together in a loving embrace. Scenes from before the Theotokos’ nativity may also be shown, such as the angel visiting Joachim in the desert to tell him of the upcoming conception, and Joachim and Anna embracing at the gateway to their house, an image also depicted separately as the “Conception of the Mother of God”. At the bottom of the Icon there is sometimes a fountain of water or water fowl in a small garden. This describes Anna’s “double lament” beneath the laurel tree of her garden, when she thought that she would neither conceive or see her husband again:

Other details which may be present are separate details of Anna, Joachim and the infant Mary together in a loving embrace. Scenes from before the Theotokos’ nativity may also be shown, such as the angel visiting Joachim in the desert to tell him of the upcoming conception, and Joachim and Anna embracing at the gateway to their house, an image also depicted separately as the “Conception of the Mother of God”. At the bottom of the Icon there is sometimes a fountain of water or water fowl in a small garden. This describes Anna’s “double lament” beneath the laurel tree of her garden, when she thought that she would neither conceive or see her husband again:Alas! Who begot me? And what womb produced me? Because I have become a curse in the presence of the sons of Israel, and I have been reproached, and they have driven me in derision out of the temple of the Lord. Alas! To what have I been likened? I am not like the fowls of the heaven, because even the fowls of the heaven are productive before You, O Lord. Alas! To what have I been likened? I am not like the beasts of the earth, because even the beasts of the earth are productive before You, O Lord. Alas! To what have I been likened? I am not like these waters, because even these waters are productive before You, O Lord. Alas! To what have I been likened? I am not like this earth, because even the earth brings forth its fruits in season, and blesses You, O Lord.

The icon of the Nativity of the Theotokos shows us the relatively exalted beginnings of Mary’s birth. Yet in her humility she does not expect the tidings that the Archangel Gabriel brings just a few years later, and bears with quietude the modest surroundings of her own Son’s birth in Bethlehem.