Mikhail Lomonosov was an outstanding scientist whose discoveries contributed to the progress of his homeland Russia and the world. Many of his achievements were far in advance of their time and remained unrecognised until many years after his death. Lomonosov identified himself as a chemist, although he also worked in many other fields and had an exceptional talent for visual arts and literature, including religious poetry. He admired the genius of Peter the Great, loved his homeland and was a devout Orthodox Christian. Today, we explore one of his major undertakings in the final years of his life.

The origins of Lomonosov’s interest in mosaics

During his lifetime (1711-1765), Italy was considered the global centre of mosaics and a prime successor to the ancient and Byzantine traditions of mosaic art. In Russia, the latest surviving examples were in Kiev, at the Cathedral of the Holy Wisdom and St. Michael’s Monastery. But the know-how had been lost, and so were the skills of making smalt.

Adept at drawing and sketching, which he learned during his extended visit to Germany from 1736 to 1738, Lomonosov caught on to the idea to revive the art of mosaics in Russia by capitalising on his extensive knowledge of physics, chemistry, geology and metallurgy.

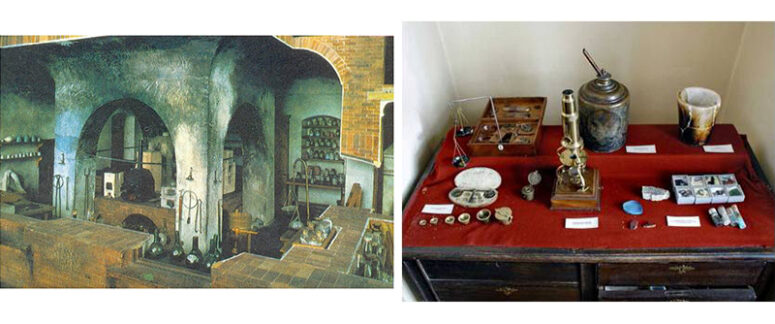

In 1742, he approached the Russian government for support in opening a laboratory, and in 1746 he finally obtained approval from the Senate.

With great zeal, he began to investigate the properties of glass, sometimes at risk to his health. His research also covered smalt, a type of glass distinct by its opacity and high density. In 1750, he produced the first local samples of smalt. But to catch up with the Italians, he still had to develop the process for obtaining a large enough variety of colours and hues. He experimented with a range of metal oxides. By 1742, he had conducted over 3000 experiments in colouring the smalt, producing a wide enough colour range for creating his first mosaic panel.

Experimental mosaics

In 1752, Lomonosov put together his first mosaic of the Virgin Mary. As Lomonosov reported, he made it from the original painting of the Italian painter Francesco Solimena. He used over 4000 pieces obtained in over 2100 experiments in a glass furnace. Lomonosov gave his work to Empress Elisabeth of Russia for her birthday. She accepted the gift with gladness and placed it in the icon corner of her royal chamber.

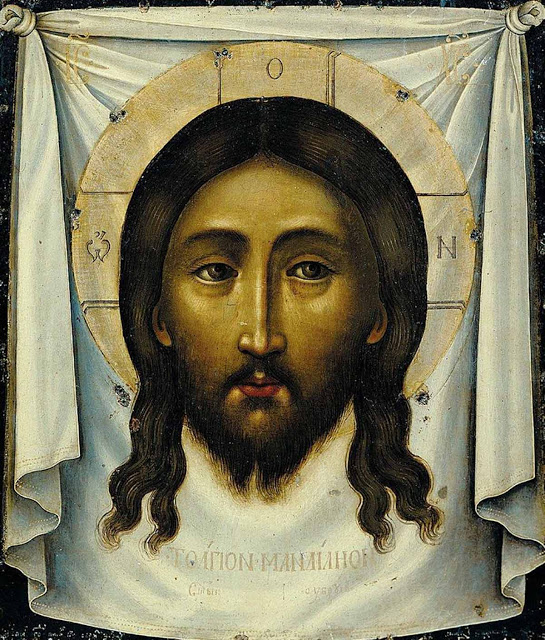

In 1953, he completed another experimental mosaic – an image of Christ not made by hand. The work was simple if not primitive in design, but Lomonosov described it as “a necessary first step”. It had been commissioned by Countess Shuvalova, a close friend of the Empress. In his letter to the Shuvalovs, Lomonosov apologised for the weaknesses of the work and its small size but underlined that it was the first trial. He asked the Shuvalovs to place it high enough above the ground to make its faults less visible and advised that it be kept under Lampads at a fair distance from the viewers. Eventually, the Shuvalovs donated the mosaic to the monastery of St. Nicholas at Malitsy under their patronage.

To move his undertaking forward, Lomonosov needed to scale up the production of the smalt. Helped by Chancellor Voronbtsov and the Shuvalovs – confidants of the Russian Empress – he secured financing from the Russian government to build a smalt factory at Ust-Rudnitsa in the governorship of St. Petersburg. His project was making progress. His two helpers, Matvey Vasilyev and Efim Melnikov – both talented artists – quickly improved the level and sophistication of the mosaics. To appreciate the progress achieved, compare the experimental works with the mosaics completed only a year later.

In the decade that ensued, Lomonosov and his team finished around 40 mosaic projects, of which 23 have survived to this day. Some are portraits of his renowned contemporaries. One notable example is the mosaic portrait of Prince Alexander Nevsky on the saint’s tomb.

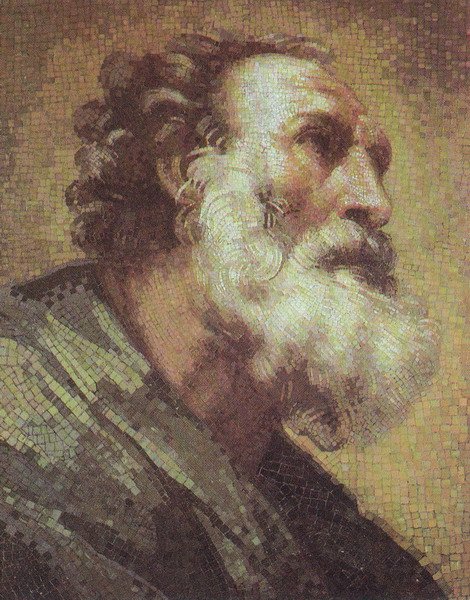

Some mosaics were religious. The mosaic of Saint Peter, one of his later works, is almost as rich in colour and sophisticated in technique as the original painting.

Perhaps the most ambitious project of Lomonosov’s studio was the mosaic panel “Battle at Poltava”, 6.4 by 4.8 metres, completed in 1764.

It was conceived as the first in a series of twelve mosaics detailing the life and accomplishments of Peter the Great to adorn the walls of the Cathedral of Sts. Peter and Paul, the resting place of the Russian Emperor. Lomonosov’s sudden death in 1765 disrupted the plan. In 1925, the mosaic was placed in the building of the Academy of Sciences, where it has remained to this day.

Lomonosov’s studio closed when the Russian government withdrew its support soon after his death.

However, his good works and accomplishments lived. His notes on the properties of smalt and smalt-making processes were not lost. Artists have continued to use them to this day to make mosaic icons in Orthodox churches. With God, nothing good is wasted or forgotten, and every good thing comes back to light again in its proper time.