2003 Cincinnati, Ohio

Almost 20 years ago, Tatiana Zhedik, one of our lay sisters, went to the USA for a summer job. As a believer, she began her acquaintance with Cincinnati by finding an Orthodox church immediately on her arrival. Weekends were Tatiana’s highest paid work hours, yet she told her boss straight away that she would be singing in church on Sundays.

One day, Tatiana met an elderly man in church. They had a conversation. Tatiana said that she was from Belarus. Shortly before she started leaving, the man came up to her, handed her a folded banknote and whispered, “This is for you.” Within a short time, the man returned twice, bringing Tatiana donations from his wife and daughter. When Tanya came home, she counted the money and realized that she was holding in her hands exactly the amount that she was “losing” by spending her working Sundays in the church.

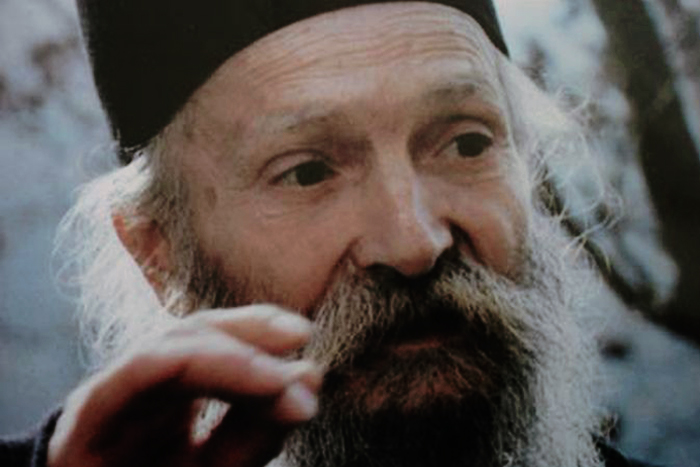

The man’s name was Sergey Kaminsky. His daughter Larisa Kaminskaya sang in the church choir. It turned out that the roots of the Kaminskys were in Belarus. However, it was not until eighteen years later that Tanya learned what they were. A year ago, Larisa posted on Facebook,”My great-grandfather, Archpriest Symeon Kaminsky was especially known as a great orator whose sermons shook the rafters and brought the faithful to tears. When you come from a stock like this, you see things differently and your tolerance for nonsense is very low.” “Interesting,” thought Tanya and asked Larisa who her great-grandfather was.

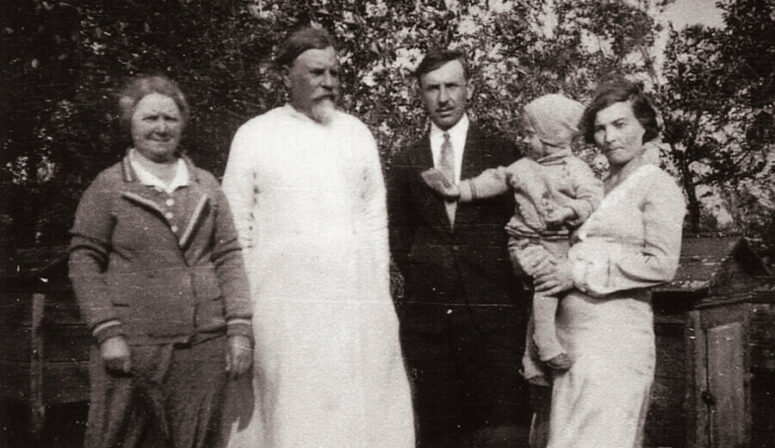

She learned that Symeon Kaminsky was a holy martyr killed for the Orthodox faith on September 22, 1939 in the barn of his own house in Gorbachi village. His son Konstantin was also a priest. After his father was murdered, Konstantin fled with his family to Vilnius and then to Poland. Then after spending several years in a refugee camp in Germany, the Kaminskys immigrated to the United States. The church in Konstantin’s native village is still in place. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Symeon’s grandchildren living in the US donated money to restore it. Father Simeon is buried in the village cemetery.

Tanya wrote to Larisa that one day she would visit her great-grandfather’s grave. Recently she was able to keep her promise.

Present Day, Gorbachi village in Grodno region

“Vasya, come here! He knows better than me,” Zinaida Pavlovna is inviting her neighbor Vasily to join our conversation. The woman is wrapped in a scarf. She has been waiting for us for a while.

There is one street and five houses in the village of Gorbachi. The oldest resident is 89. Of course, all the eyewitnesses of those events have already died. Even the parents of those alive today were still children back then. Vasily finally comes leaning on a stick. He lives in a green wooden house nearby.

“This old man knows more than I do, so ask him,” Zinaida brings us closer to Vasily. “I was born in another village, but I spent most of my life here, since I was twelve. I worked long hours teaching Russian at school. I physically had no time for this.”

“What can I say?” Vasily shakes his head, “If you came at least a year and a half ago, the old women were still alive who knew something about it. They have already died. My wife knew everything, but not me. I had no time to delve into what the women said. I went to work at the collective farm in the morning and returned home in the evening, and that was it. “It is hard to say who the killers were. Some say one thing while others say another. According to one version, the soldiers killed him, but who knows if it is true or not? Another version is that the local communists did it. The old people used to say that. As for me, I was still young then. The youth did not care much then. “The women from the village of Chaplichi washed the body and buried it. They sang in the church there. They are long gone, even their children have already died. It was a long time ago…”

We are standing in front of the stone church of the Dormition of the Blessed Virgin, built in 1860. Around the church building, there are huge sawn trunks of rotten trees, possibly of the same age as the church. Although not destroyed, the church had been closed until 1990. A young priest, Fr Vladimir Grishkevich, has been serving here for eight years now; besides the village of Gorbachi, he has two more parishes. There are hardly any parishioners here. Yet, services are held twice a month.

The sign next to the church entrance was made in 2018, on the Feast of the Synaxis of New Martyrs and Confessors of Belarus. The inscription on it says, “This memorial was erected in memory of priest Simeon Kaminsky, innocently killed by the Red Army”.

Zinaida Pavlovna is keeping her posture as she speaks loudly, even solemnly, as if she were teaching a class at the blackboard.

“In Soviet times, our local people did not allow them to use the church as a grain storage. They just did not let that happen,” she says sternly. “My grandmother with several other women stood like a wall against the “innovators” until they finally turned around and left. This is the way our grandmothers were. “They took the church utensils and icons to other churches. When the church was re-opened in 1991, they were able to get some of that back and replaced the rest with new items. The church was opened thanks to Kaminsky’s grandson Yaroslav. “It would not have been possible without him. I am a hundred percent sure of that, because when they went around the villages to collect money for restoration, most people would donate a few kopecks or a ruble at the most.”

“At that time, one ruble was a lot of money,” Vasily adds. “I worked all day for 20 kopeeks.”

“Simeon’s grandson Yaroslav lived in Washington,” Zinaida continues. “He knew that his grandfather was buried here, and he started this in memory of him. Twice he transferred money to Priest Gleb Pavlovich Yakunin in Moscow, who then travelled all the way from there and brought it here, despite the distance. He did not take a penny for himself and brought the money here to open the church. These were very large sums of money at that time. This is how people should be, I think. This is a real act of faith. “Some time in the early 2000s, Yaroslav came here in person. He was interested to see how the church was rebuilt. Besides, he wanted to visit the grave of his grandfather.

“I live alone, just me and my chickens,” Zinaida Pavlovna leads us past the empty houses. “My children live in cities. When my daughter took me to Minsk, I stayed there for a week before I knew I had to go back. I could not stand it. I was literally suffocating there. I prefer to die here. “It is only old people who live here, but as long as there is a church, the village will live. I believe so. I know. It is for a reason that it was restored. It was possible thanks to these people, the Kaminskys.

“My mother used to graze their cows. She was 10 years old then, and Yaroslav was even younger. She remembered him well. He had blond hair. “Mom said that when he arrived in 2000 and saw her, he hugged her and stroked her head very gently… He was so happy that he met these people! Mom said that she would not have recognized him, from a blond boy he had turned into a red-haired old man, and still he recognized her… “Mom died ten years ago. He brought her a small icon from America. I keep it to this day as a memory.

“He gave the woman in the church shop some money and asked her to take care of his grandfather’s grave.

What a good memory he had! Mom said that he remembered many things from when he was a child. He was a child when he left here, yet he remembered the river mill outside the village. “He also remembered the oak. Their family planted an oak tree. When Yaroslav came, he asked my mother to take him to this tree. She led him there. This oak is now a tall beautiful tree on the corner of the village.” On the site of the Kaminskys’ house, there is a farm stay now.

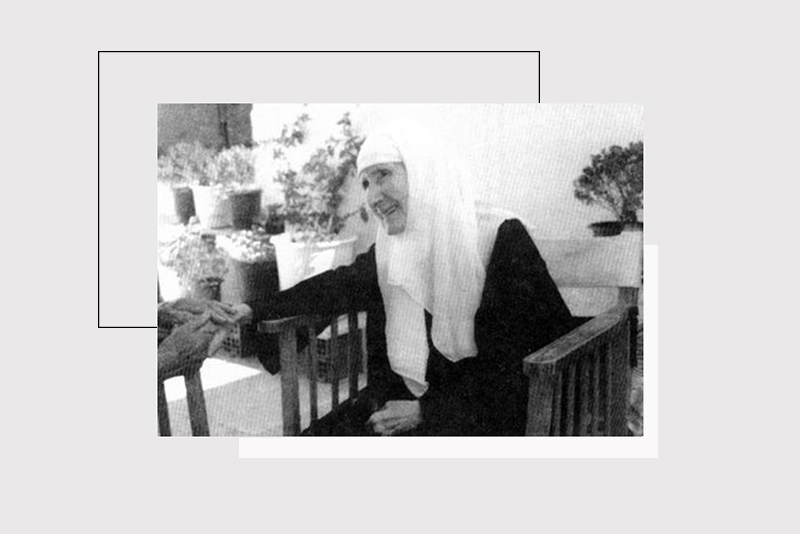

After the death of Fr Simeon, his daughter Tatyana stayed in Poland. In 2003, Tatiana published the story of her father’s life and death in the Polish Orthodox magazine Tserkovny Vestnik (Church Reporter).

Archpriest Simeon Kaminsky was born in 1877 in the village of Gnoino, Bialsky District. His parents were peasants, primarily involved in agriculture. He finished a teachers college in the city of Kholm and started working as a teacher in a rural school. Then he entered a theological seminary. He married and had a son and a daughter. In 1915, with the war front approaching, he was forced to leave for Rostov-on-Don. There he was assigned to a village parish and became rector of an old cathedral.

According to Tatiana Kaminsky, The Cossacks and the parishioners came to love her father. “They even accepted my father and brother into the Cossack brotherhood,” she writes in her memories, “and allotted them tracks of land.” “After the Bolshevik victory, the most difficult period of our lives began. There was a terrible famine in Russia in the years 1919-1920. People were dying in the streets and there was no one to bury them. “Winter was the hardest. My mother would go to farms and trade whatever clothing and other items we had for food. My father and brother would try to catch some fish through holes in the river ice. “I recall that the Communists often called Father to their meetings, after which he would come home barely alive.

“I remember, once in a very hungry time after the spring flood of the Don River, my father and brother were catching fish with nets and caught a lot of it. People were already waiting for them on the shore, and they distributed everything they had among the hungry residents.”

In 1922, the Kaminsky family returned to their homeland. Simeon Kaminsky went to the Warsaw Metropolis for permission to petition the local authorities to open a parish. In 1923, the parish was opened in Fr Simeon’s native village of Gnoino, where he was born. The church house, land and estate were returned.

“The house was empty, and we had nothing with us. During this difficult time, Father’s friend arrived from America. Prior to the war, Father had helped him emigrate by lending him some money for the journey. “The man repaid the debt, and we bought ourselves a cow with the money. So began our small farm.

Our parish did not have a psalm-reader, so my brother and mother directed the choir themselves. “My father had great zeal for Orthodoxy and often preached at parish feasts and in district parishes. I remember his sermon in a forest spot in the Tokarski parish, where miracles had occurred. “It was the third day of the Pentecost. There was a multitude of people there. Many of them were crying while listening to my father’s preaching. After the service, people came to my father in gratitude, requesting his blessing.

“In his struggle for the Holy Orthodox Faith, my father was deprived of citizenship. My parents were forced to leave the place where they were born and move to the Grodno diocese.”

A few years later, a tragedy happened in the Kaminsky family…

First, the place where the Kaminskys lived became a hospital, and then it was turned into a stable. Later, it was used as a collective farm hostel accommodating students for many years. Eventually, the large premises fell into dispair. Six years ago, a married couple bought it and turned the place into a farm stay. “These young people have beautified the abandoned lot. They even dug out a pond. Today they help me support myself,” says Zinaida Pavlovna.

As we approach the gates of the estate, the hostess opens the door. Zinaida Pavlovna asks permission to show us the oak tree and leads us through the premises.

“This is the place where the Kaminskys lived. Nothing is left of what was here before. The Kaminskys’ large territory where my mother used to graze cows was later overgrown with brushwood. This area has now been landscaped and beautified. Visitors are always delighted with their visits to this place.

Inside the homestead there is a space with several halls, used for weddings by couples both from nearby and distant places. On the premises there is a pond, many large stones and old trees.

Once, a neighbor wanted to get rid of these trees.He cut down a few of them and was about to continue when I told him, ‘You did not plant them, and you have no right to cut them down.’ I called the village council; the chairman came and he did not allow it. Yes, I am the head of the village and I will stand for this,” says Zinaida.

I look at her and imagine her grandmother, who once did not allow for the church to be closed. We are walking along the path to the oak tree.

“Look how big and beautiful this oak is! We have always admired it,” she says with affection.

The oak branches have spread out, forming a shed over this land. The trees look naked without their leaves, making you want to stand close to them, touching and examining the old bark, as if trying to read the history of this family in its cracks.

Tatiana approaches the old oak, trying to hug its trunk covered with soft moss. She looks very small against the background of the giant tree as she takes a photo of it and immediately sends it to Larisa, the great-granddaughter of Father Simeon, living in the US. Larisa writes back: “This is incredible. I cannot believe this is happening! Visiting the grave of my great-grandfather and the place where he lived and died is my greatest desire. A deep inner relationship with him has always been part of my mentality. I have been greatly influenced by this invisible connection with him. As a family, we have always prayed for him and his wife.”

Many times Larisa has tried to come to the village of Gorbachi, but due to various circumstances it did not work out. Larisa is a church choir director; her four children also sing on the kliros. She writes that she has always felt it was her duty to continue the work begun by her great-grandfather, preserving the spiritual legacy passed on to his children and grandchildren, forced to flee and build a new life without him.

“I am very proud to be a member of the Kaminsky family,” she says, “and a descendant of a new martyr. I am very proud to be Russian Orthodox; not proud in a sinful way, rather I feel very honoured and humbled to have been given this legacy. I have been doing my best not to waste it, trying to preserve it to the best of my ability both in myself and in my family.”

In 1938 Father Simeon was transferred to the parish in Svisloch village. His son Fr. Konstantin was the rector in Levshovo (now Gorbachi), a village eight kilometers from Svisloch. In his sermons, he often criticised Communists. The well-disposed parishioners used to warn him of a danger to his life. Eventually, Fr. Konstantin decided to leave for the West. He tried to convince his father to join him, but Fr. Simeon categorically refused.

On September 20, Fr. Konstantin left for Svisloch and from there, he moved to Vilno. Fr. Simeon remained at his parish. On the tragic day of September 22, he was brutally murdered. How exactly did the murder happen in 1939? The old oak tree is likely the only keeper of that secret. Zinaida leads us to the scene of the tragedy.

“Here, in this place where the firewood is now stacked you can see the foundation of what used to be a barn,” says Zinaida. “It was large enough for keeping cattle. There are different versions. According to some, he was killed inside this barn, while others say that it happened behind it. This barn has been up for a long time. When the hospital was built here, they used it for storing firewood. Apparently, there were witnesses who saw everything. They wanted to take Father Simeon’s horse, so they went to the barn…”

Not so long ago, old.orthos.org published the testimony of Tatiana Pavlovna Ostasheva, a resident of the village of Zhilichi. She recalls, “Of course, many years have passed and many things have faded from memory, but the fact that Father Simeon was killed is something that my brother asked me to always remember and to tell others. My older brother Vladimir was then a shepherd at the Kaminskys’. He was 10 years old. On that September morning in 1939, Vladimir suspected nothing as he drove the cows out to pasture and started waiting for someone to bring him breakfast from the priest’s house. He clearly remembered seeing two men escort the priest out of his house and lead him to the stable at the sight of a rifle. One of the men was dressed in a military uniform, and the other was a civilian, from the locals. My brother was peeking through a crack in the barn, and the gunmen could not see him. There was a sheaf of freshly threshed straw in the shed, which they ordered Fr. Simeon to untie and spread on the floor. Father started spreading the straw, and at that moment they fired at him from the back. The shot rang out, and the priest slowly began to rise to his full height, and then fell on the straw face up…”

“Everything that has happened is part of God’s Providence. The question of forgiving the killer never even arose in our family,” Larisa, once wrote to Tatiana. “Matushka Elena, Fr. Simeon’s wife never spoke with anger or bitterness about what had happened to her husband, or their forced move to the USA, although she was very sad and missed her husband. I suppose there was no need to talk about forgiveness. It was self-evident.”

“Everything here is covered in obscurity. The 20th century is not a happy one,” Fr. Vladimir, priest of the church where the martyred Fr. Simeon Kaminsky once served, tells us. “Our land is soaked in blood; we do not know what we are walking on.

When they built the farm stay here, people began to come to our parish for Baptisms, Weddings, which they can now celebrate at the newly-built place. I think it is a good thing.

At one time, someone wanted to buy this memorable place and found a monastery here, but it did not work out. We have raised the question of canonization, but it is not an easy process. We are missing some important documents. Canonization requires serious work with the archives. It is now being treated very meticulously.

We, Christians, need to know the past, avoid dwelling on the present and move into the future, in spite of anything. The Lord gave us the means, the motivation and the destination.”

We follow the road leading from behind the church to the cemetery, surrounded by a field on four sides. The cemetery is very old. The wind blows in our faces, tearing the crumpled dry leaves off the branches. We walk through the graves until finally we find the grave of Father Simeon Kaminsky, surrounded with an old metal fence covered with moss. The grave looks inconspicuous. The inscription on the granite monument says: “Kingdom of Heaven and Eternal Rest, Dear Father.”

“Every year, on September 19 or after September 21, we celebrate a funeral service for Priest Simeon Kaminsky here, at the grave,” says Father Vladimir. “On this day, people gather to honor his memory. We need to remember… And as long as the locals keep the memory, we will continue to serve.”

“Has anyone ever come to Fr. Simeon’s grave, because they knew this story?” we asked Fr. Vladimir.

“As far as I can remember, you are the first.”

“Why do you think Father Simeon preferred to stay, instead of leaving together with his family?”

“Every soul is a mystery. Today we can only guess what really happened… According to the locals, he knew that he was going to be killed. He was shot after the Nativity of the Holy Virgin, and on that day his son was supposed to serve. Father Simeon knew that they would come for him, and saved his son by serving in his place. ‘You only die once,’ he said shortly before his death. It is a true Christian act and a good example to follow, especially in difficult times. For the Kaminskys, Father Simeon has become the cornerstone from which the great construction of Christianity began in their family.”

There was once a big old tree growing on the grounds of the farmstead and the Kaminskys’ former home. All that was left of it was a stump, which eventually rotted away. Before it did, however, a dense canopy of linden trees grew around it. That tree, having died, gave life to new ones. Perhaps it is the same with the life and death of a person who can “nourish” the branches of his kind until they begin to grow together, as if holding hands. Their roots go deep into the earth, where they draw their strength, while with their tops they reach into the sky…

Source: https://obitel-minsk.org/en/time-travel-part-1

https://obitel-minsk.org/en/time-travel-part-2

Thank you so much for this-so inspiring and uplifting too