The canon is one genre in church hymnography with which we are perfectly familiar in practice, so this time we will talk about theory.

The liturgical themes are dry enough in themselves; like jurisprudence or law, they become interesting only when they have a practical application. However, let us slightly expand our theoretical knowledge of the canons, the regular reading of which is practised by each of us without exception.

Translated from the Greek κανών means “a rule” or “measure”. Today, canons have become one of the key genres in pan-Orthodox hymnography. However, they did not acquire their modern look instantly. For example, in the tradition of the Palestinian monks, the term canon meant the sequence of daily prayers. The life of St. Sabbas the Sanctified tells us about the obligatory canon of singing psalms, which became the prototype of the future Book of Hours. From the same source, we learn that Matins, the main divine service of the daily worship cycle, is called the “night canon”.

The canon acquired its present form by the VIII century, which also happened in the Palestinian environment. One of the main elements of Matins was the singing of biblical canticles interspersed with troparia. This tradition was characteristic of both monastic and cathedral worship in Palestine. Gradually, it regained its former name of matins, and ceased to be called “a canon“.

By its internal structure, the canon is a complex one-stanza hymn, consisting of several cycles called odes. They are built in such a way that each irmos is related to the topic of the corresponding biblical song of the Matins. It can convey a summary of the song, include a direct quotation from the Bible or give its allegorical interpretation.

If we delve into the canons that we read, we are certain to notice how they reflect the topics of the irmoi.

The first ode always contains a reference to the words of gratitude that Moses spoke after the miraculous passage of the chosen people through the Red Sea. The second ode is penitential; it is absent from most of the canons, and used predominantly during Great Lent, as it corresponds to its mood. The irmos of the third ode dwells on the song of thanksgiving, sung by St. Anna (the mother of the prophet Samuel) thus symbolizing our gratitude to God. The fourth ode is the prayer of the prophet Habakkuk, in which he sings of the Lord’s salvation for all of us. The fifth irmos reflects on the words of the prophet Isaiah, who foresaw the coming of the Messiah and the general resurrection before the Last Judgement. In the sixth irmos, we see the prayer of the prophet Jonah, whom the Lord released from the belly of the whale in the same way as He delivers us from hell. The seventh and eighth irmoi are the songs of the three youths — friends of the prophet Daniel, miraculously rescued from the furnace fire after refusing to bow to the idol. Finally, the ninth irmos is associated with the song of the Holy Virgin during her meeting with Elizabeth, or the prayer of Zechariah, the father of John the Baptist, after miraculously recovering his speech.

In addition, irmoi set the metrical and melodic model of the subsequent troparia. In some known canons, the first letters of troparia form an acrostic. Such canons have been composed by well-known hymnographers, such as St. John of Damascus, St. Romanos the Melodist and Theodore the Studite.

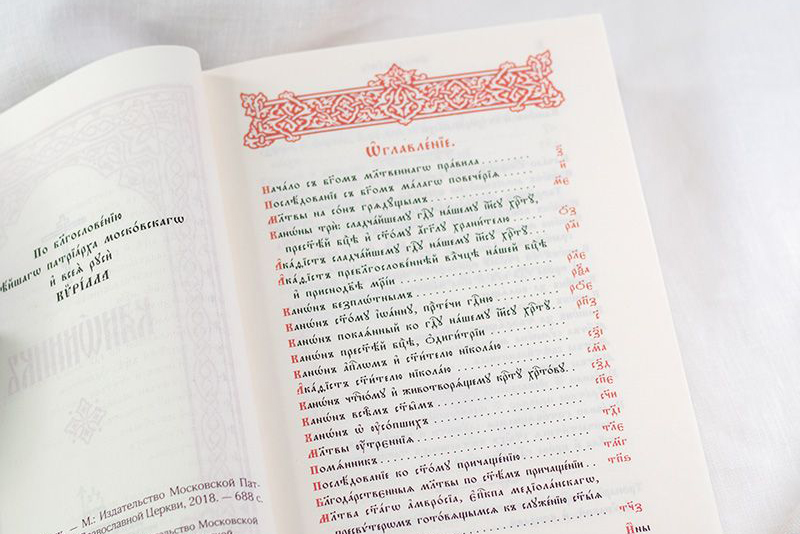

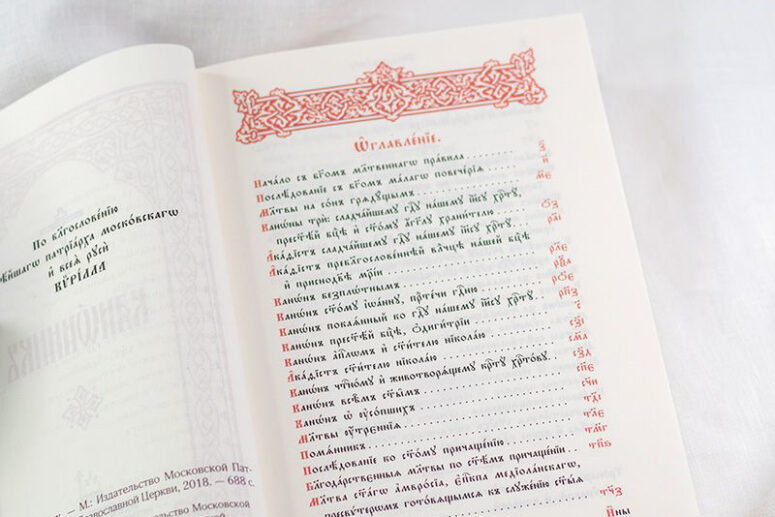

Thousands of canons have survived to this day, and only a small part of them has been included in the liturgical books that we use. For the most part, canons have been written specifically for church services, while some are composed for personal prayer or simply for the sake of gaining hymnographic experience.

In fairness, the most used canons in today’s worship owe their popularity to being included in the first printed books, whose compilers were neither always guided by the best ancient manuscripts nor had a full-fledged source base. Despite this, canons perfectly convey the meaning of feasts and memorial dates, which is why the righteous John of Kronstadt, for example, preferred to personally read canons during the Matins service.

As we understand from the above, Matins was the service originally containing the singing of the canons. Today, canons are also included in the Compline, memorial, funeral and prayer services, as well as the sacrament of Unction. The Typicon prescribes adding fourteen troparia to each irmos during Matins, with the exception of major feasts, when twelve troparia are sung, and the first day of Easter, when their number reaches sixteen. These figures are achieved by combining several canons, usually no more than four. In practice, in each parish, the number of troparia can be reduced at the request of the rector, the serving priest, or according to the established tradition.

Most often, we read canons while preparing for Communion, but this does not mean that we should not listen to them in church. Today we have every opportunity to familiarize ourselves with the liturgical canons. Perhaps, it is sometimes worth putting aside the prayer book and taking up the canons of a particular feast or a revered saint in order to partake of the liturgical treasury of the Orthodox Church.

Translated by The Catalogue of Good Deeds

Source: https://spzh.news/ru/istorija-i-kulytrua/89405-kanon–samyj-izvestnyj-i-neznakomyj-zhanr-cerkovnogo-pesnopenija