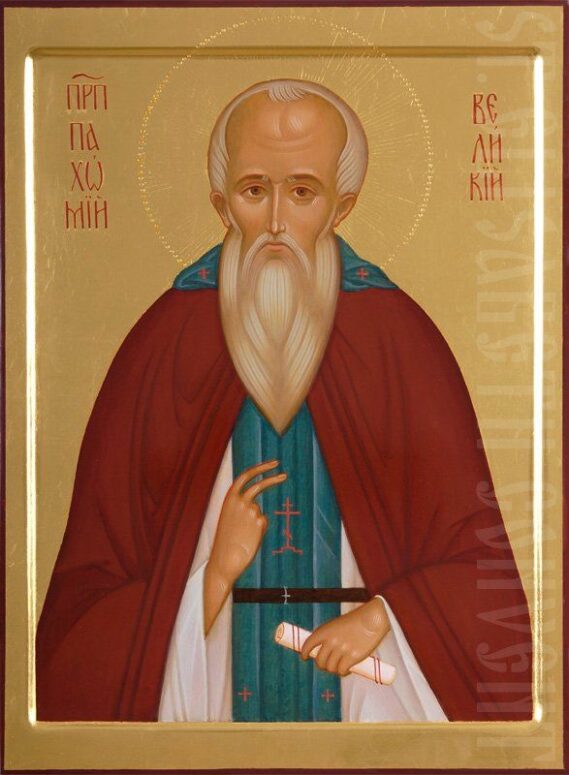

St. Anthony the Great is honoured as the father of coenobitic monasticism. Yet the Venerable Pachmius the Great takes the credit for establishing the first monastery and drawing up its monastic rule. What was the life of a monastic like at this first monastery, and why do its practices matter for present-day monastics?

Rules and practices

As we read in his life, St Pachomius was praying in the Tabenae desert when the voice from above commanded him to stay and establish a monastery. Immediately, an angel dressed as a hieromonk descended on him and handed him a copper plaque with nineteen monastic rules inscribed. Subsequently, the Venerable Pachomius added more rules to these nineteen.

Abbot Pachomius considered himself responsible for all aspects of the monastery’s life. Monastics were living in cells with 300 brethren. For each cell, a responsible monastic was assigned to manage its economic activity. Dedicating himself fully to giving spiritual guidance to the brethren, Abbot Pachomius still found time to oversee the monastery’s economy.

Monastic supported themselves by making merchandise and selling it in the open market. Ropes and burlap were the most marketable commodities. Under the monastic rule received from the angel, every brother had a production target based on his strength and capabilities. No brother could perform below the target except because of sickness or infirmity. Overperforming was also discouraged. Healthier and stronger brothers had higher targets, while the sick and the infirm had minimal ones.

The monastery’s prayer life consisted mostly of communal prayer meetings. The brethren met three times daily – at noon, at sunset and midnight. Psalm singing was followed by readings from the Old and New Testaments. A set of six evening prayers were said after sunset. There was also an additional session at three in the afternoon, dedicated only to psalms. Altogether, the monks read twelve psalms per day. A vespers service was celebrated each Saturday night, lasting until the fourth crowing of the roosters in the early hours of Sunday.

The monastery had no permanent clergy. Abbot Pachomius believed that having clergy would put some brothers above others and generate tensions and jealousy. Only on great feasts would he invite a priest from outside to serve the liturgy. Therefore, it was common practice among the monastics to administer the Communion among themselves. Everyone was required to gather for Communion each Saturday and Sunday.

The material standard of life was modest. Monastics had no personal possessions except clothing. The diet was mostly of bread, salt, vegetables, cereals, fruit and herbs with vinegar or oil. The sick and the infirm were offered wine, fish and even meat.

Every monastic was allowed as much food as they wanted. Fasting was a right, not an obligation. The penances assigned to monks for misdemeanours were generally as lenient as the fasting rules. A monk was told to stand when the rest were seated for being late for prayer or the abbot’s talk. A monk who was late for a meal had to skip it. The punishment for idle talk over a meal or during prayer was leaving the ceremony until it was over. Serious offences such as theft were punished with beatings or deprivation of food or drink. Monks were verbally censored for laziness or procrastination. If that did not help, they were sent away to the infirmary where they were given food, but no work, in the expectation that forced idleness would change their attitude toward work. Transgressions committed through ignorance carried no penalty.

Joining the monastery was no easy task. Aspiring monastics were made to wait outside the gate for several days. Only then would they be allowed into the guesthouse, where they would spend weeks or even months. They spent the trial period memorising the Psalter. A monastic was assigned to ask the new arrival from time to time if he had changed his mind about joining.

If the candidate’s motives proved sincere, he was admitted to the community as a novice. He would remain a novice for at least three years to become attuned to monastic life and have time to learn the Holy Scripture. Monks needed to know from memory the monastic rule, the Psalter and the Scripture. Memorising all these texts was not a goal in itself, but a way to attune oneself to the hard work of spiritual ascent to which a monastic must dedicate all his life.

Spiritual and moral rules

Monks spent most of the day in silence. They kept silent during work and most other activities and spent this time in contemplation on a recently memorised Scripture passage and reflections on all aspects of its meaning and teachings. They could not go over to another passage until they had explored every layer of its meaning. Therefore, the contemplation could last days and even months.

If a monk encountered in his reflections a question that he could not answer himself, he would refer it to the Abbot during his next talk. Abbot Pachomius gave talks every evening. His successors had meetings with the monks on Saturdays and twice on Sundays. The frequency of the meetings, however, was at the abbot’s discretion.

After each meeting, the monks would discuss Abbot’s words and reflect on them to reap good spiritual fruit.

Reading took a prominent place among the occupations of monastics. The monastic library’s holdings had the Holy scriptures and writings of the Holy Fathers. Each Monday morning a designated brother made a round of all the cells to collect book requests and spent the rest of the week delivering the books. The chief monk of the cell safe kept the books. He gave them to the brothers in the morning and collected them in the evening. All the books returned to the library on Saturday because the librarian’s mandate lasted only a week. How the brothers found time to read is still a mystery, as the monastic routine offered few opportunities for reading.

The moral practices of the monks rested on several pillars: silence, obedience, non-possession, fasting, abstinence, humility and mutual love.

As already stated, the monks kept silent most of the time. They could break the silence only to discuss a spiritual question or a work-related matter. The silence was the central instrument of contemplation and reflection about God.

For a monk, obedience was almost equivalent to the denial of one’s will. To obey meant to do only what was permitted by the rules or allowed by the Abbot. Full obedience to one’s spiritual guide and the monastic rule was seen as obedience to God Himself.

The monks’ habits were their only possession. They were made of the cheapest material. No monk, not even an abbot, could own anything else. The brothers treated the books and the tools they used for work as the property of others.

Although everyone was free to eat as much as they wanted, most brethren could eat as much as they wanted, and limited themselves in food voluntarily. Some vowed to eat nothing but bread and salt, others ate once in several days. Food was allowed only in the refectory, but not in the living quarters.

Monks walked with their heads bowed and wearing a kukol at all times for humility, to avoid looking at others as they pray, eat or work. The monastery was not a place for idle talk, fun, or laughing.

Love of God and one’s neighbour was the cornerstone of monastic life. The spirit of love permeated the monastic rules, despite their strictness.

It was forbidden to create unnecessary hardships for a brother. A brother who was exhausted from work was excused from the evening prayer. Brothers who needed extended rest typically had their request granted.

Responsible monks were tasked with seeing that no one was in sadness or despair. They had the duty to give reassurance to everyone who needed it and were subject to strict penance if they neglected to do so.

More generally, strict punishments were meted out to those who did not give love to their brothers, raised false accusations, or were wrathful and quarrelsome. In extreme cases, the monks who persisted in their sin could be expelled.

Relevance for the present

The monastic practices described so far were established 1500 years ago. Do they have any relevance to present-day monasticism? Certainly so, and in many respects. The monastic virtues of love, obedience, non-possession, and abstinence are still the pillars of monasticism.

The most visible distinctions are of the form. Most Orthodox monasteries are far more open to the world than in ancient times. The monastic rule of Saint Pachomius covered all aspects of monastic life down to the finest details, and new rules were added to it all the time. This situation is no longer typical of present-day monasteries.

However, the essence of monastic life has not changed. The Eucharist, prayer, fasting, obedience, work and contemplation of God are still its pillars. Change has only affected the form. For example, the Eucharist is now administered only at church by an ordained priest or bishop, and prayer gatherings are less important than church worship.

Yet from the monastery established by Saint Pakhomius, we have inherited some of the most fundamental features of monastic life that will remain relevant for centuries: spiritual discipleship, the guardianship of a more experienced monk, the spiritual father, over his less experienced brother; the prevalence of love over the letter of the law, equality of the brothers, and extensive freedom of spiritual practice enjoyed by every monk. Every brother worked to the best of their ability, and everyone was treated with love and respect. A visible expression of these values is the duty of care and reassurance borne by the monks toward their brethren. Remarkably, the freedom enjoyed by every monk motivated him not to slacken up but to exercise his inner discipline. This is perhaps the most valuable legacy of the Tabenae Monastery for modern-day monasticism.