Tertullian clearly writes about the significance of the sign of the cross in the life of the ancient Christians, “At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign (De corona, ch. 3). This article discusses the history of the sign of the cross, focusing on why the ancient Christians adhered to this practice and in what manner.

It is impossible to say exactly when and where the tradition of making the sign of the cross came from. Mentioning it as early as in the 4th century, among those, whose origin is unknown, St Basil the Great said that no one had left us a written instruction on making the sign of the cross. According to St Basil, such practices have been secretly received from apostolic tradition and are as important for piety as those that have been explicitly left by Scripture or the saints. Rejection of such traditions is tantamount to distorting the Gospel (On the Holy Spirit, ch. 27).

We can nonetheless try to trace the origins of this tradition. In the time of Christ, in synagogue worship, there was a rite of inscribing the name of God on the forehead, originating from the book of the prophet Ezekiel. Ezek. 9 speaks of a vision of God’s visitation of Jerusalem. Punishment was supposed to befall everyone, except those on whose foreheads the angel of God would depict a certain sign.“(The Lord) said to him, “Go through the city, through Jerusalem, and put a mark on the foreheads of those who sigh and groan over all the abominations that are committed in it”” (Ezekiel 9:4).

Mentions of similar inscriptions can be found in the Revelation of John the Theologian. “Then I looked, and there was the Lamb, standing on Mount Zion! And with him were one hundred forty-four thousand who had his name and his Father’s name written on their foreheads” (Rev. 14:1); “Nothing accursed will be found there any more. But the throne of God and of the Lamb will be in it, and his servants will worship him; they will see his face, and his name will be on their foreheads” (Rev. 22:3-4).

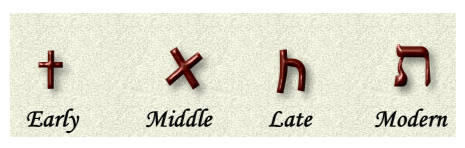

The Jews symbolically inscribed the name of God with the first (Aleph) and last (Tav) letters of the alphabet. This was done to signify the Infinity and Omnipotence of God, containing in Himself the fullness of perfection. Similarly, the Lord will say of Himself in Revelation: “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end” (Rev. 21:6). Gradually, the two letters were replaced by the only letter Tav, inscribed on the forehead.

N.B., at that time the letter Tav resembled a small cross.

The remaining testimonies about the manner in which the sign of the cross was made by the ancient Christians speak in favour of the custom being adopted from the Old Testament religion. According to most of them, the sign of the cross was made on the forehead. We have already mentioned one of such testimonies in the beginning of the article.

There are also mentions of cases when the sign of the cross was performed over the mouth or the whole body: “Raising her finger also to her mouth she made the sign of the cross upon her lips,”Jerome, Letter 108 (to Eustochium); “Shall you escape notice when you sign your bed, (or) your body?” (Tertullian, Ad Uxorem, b. 2 ch. 4)

Most often, the sign of the cross was made with only one finger, (a thumb or forefinger). A description of such a sign of the cross can be found in the Panarion, a work by Epiphanius of Cyprus. “Tracing the sign of the cross on the vessel with his own finger, and invoking the name of Jesus, he cried out…” (Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion, Against Ebionites, ch. 12)

There are also examples of the sign of the cross being made with the whole hand. “The pious man Honoratus … calling upon the name of Christ several times and putting forth his right hand, made with it the sign of the cross” (Gregory the Great, Dialogues, b. 1 ch. 1).

It can be concluded that there was no uniformity in the manner of performing the sign of the cross in antiquity, although the predominant way was to do it on the forehead with one finger. The sequence in which the sign of the cross was made remains unknown. Although it is likely that the tradition itself passed down to us from the Old Testament religion, in the patristic interpretive tradition, the sign of the cross is unequivocally perceived as a sign of the cross of Christ.

As already noted, the Fathers urged Christians to cross themselves as often as possible and on every occasion. In some cases, making the sign of the cross was an absolute necessity. St John Chrysostom exhorts Christians to make it as a protection from evil spirits, in case of a need to enter a synagogue or a pagan temple. “But how will you go into the synagogue? If you make the sign of the cross on your forehead, the evil power that dwells in the synagogue immediately takes to flight” (St. John Chrysostom Against the Jews. Homily 8).

It was considered obligatory to make the sign of the cross before meals. Both in the East and in the West there are stories about the sign of the cross saving from poison. They described cases when people made the sign of the cross, drank poison and remained unharmed. For example, a bowl of poison, overshadowed by the sign of the cross by St Benedict of Nursia, completely fell apart (Gregory the Great, Dialogues, book 2, ch. 3).

A common reason for making the sign of the cross, mentioned by the holy fathers, is the struggle with passions and sorrows. Often the need to cross oneself is caused by the influence of unclean forces, in which context the sign of the cross is spoken of as an invisible seal driving away the devil and demons.

In monastic literature, the sign of the cross became one of the main means of healing. For example, St Theodoret described a healing, performed by Peter the Ascetic, who “putting his hand on the patient’s eye, made the sign of the saving cross, causing the disease to immediately disappear” (Church History).

The sign of the cross was revered and helped believers so much that even pagans began to resort to it. For example, the emperor Julian the Apostate, after he had already renounced his faith, once became frightened and crossed himself (ibid.) Theophylact Simocatta testifies of captive pagan barbarians who, at the insistence of their parents, had the signs of the cross on their foreheads from childhood, to save them from illnesses (Theophylact Simocatta, History).

Obviously, the sign of the cross was an inseparable element of life for the ancient Christians, helping them to constantly keep their minds in the Lord, protecting and giving spiritual and physical strength to believers.

The importance of the sign of the cross is best described by St Ephraim the Syrian, “Instead of a shield, protect yourself with the True Holy Cross, marking your limbs and heart with it. Use the sign of the cross to overshadow yourself not only with your hand, but also in your thoughts mark with it your every occupation at the times: your arrival and your departure, your resting and rising, your bed, and whatever service you go through – first cross everything in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit. This weapon is very strong, and no one can ever harm you if you are protected by it” (Ephraim the Syrian, On a Monk’s Armour).