Altar barriers have been known since the very first centuries of Christianity. However, the Russian iconostasis did not acquire its present form (a high wall, composed of several tiers with icons) until the 17th century. Fundamental changes have occurred not only in the appearance of the altar barrier, but also in the interpretation of its purpose.

The first altar barriers (1st through 3rd centuries), known from house churches and Roman catacombs, were low lattice partitions. They were installed in churches so that the clergy could freely perform worship, avoiding the pressure of the crowd. This was particularly important, since large numbers of believers gathered in small house churches. At the same time, these barriers did not obstruct the view of the altar to the laity.

After the fourth century, altar barriers made of 1 – 1.15 metre-high vertical stone slabs began to become more and more spread until they almost completely replaced the lattice walls by the 5th-6th centuries.

For a long time, altar barriers were rarely higher than the average person’s chest level. The first altar barriers, exceeding human height and blocking the view of the altar, appeared at the initiative of St Basil the Great (4th century). According to the life of St Basil, once during a celebration of the liturgy he noticed that a deacon serving with him was winking at a woman standing not far from the altar. St Basil then ordered to increase the height of the altar barrier in order to avoid such cases in the future.

However, low altar barriers, not obstructing the view of the altar, remained common until the 6th century. At the same time, the altar table was commonly placed under a ciborium, a canopy on four pillars with curtains, drawn at certain moments of the service in the same way as catapetasma.

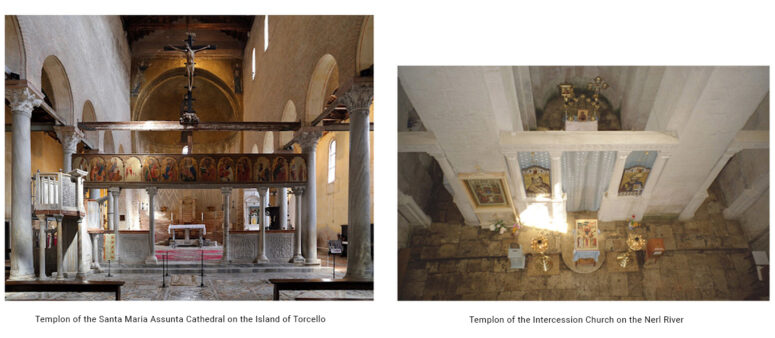

Hagia Sophia, built in the 6th century, became a symbol of the Byzantine “golden age” and significantly influenced all subsequent church architecture and art. That influence was also applied to altars. Many church architects began to follow the model of Hagia Sophia, surrounding the altar with a templon, a colonnade with an architrave (overhead horizontal beam connecting the columns).

The gaps between the columns were originally closed with curtains, but this practice did not last. In some cases, the floor space between the columns was partitioned with stone slabs. The architrave was decorated with carvings and mosaics, and over time, in the Eastern tradition, it also began to be used for placing icons. This is how the first iconostases appeared.

Such templons served as prototypes of the Eastern iconostases, while their Western descendants, due to liturgical differences, remained virtually unchanged, sometimes returning to simpler and more ancient forms, or even being completely abandoned.

There were some completely different traditions as well. For example, in the Eastern Assyrian Church of that time, altar barriers followed the pattern of the Jerusalem temple and were designed as blank walls with one or three doors.

The practice of decorating the altar barrier with icons becomes widespread with the end of iconoclasm. The most frequently used icons in altar iconostases were the feasts of the Lord and the Theotokos, as well as the Deesis. Images of local saints as well as icons of saints or events in honour of which a particular church was consecrated were also sometimes used.

Icons began to be placed in the gaps between or hung on the columns; sometimes they were written on the actual columns. A long painted or carved panel with the most significant icons was also installed on the architrave. That was the end point in the evolution of the Byzantine altar barriers.

In Russia, altar barriers were slightly different from the Byzantine ones. Unlike their Byzantine counterparts, mostly made of marble and stone, Russian altar barriers were typically made of wood, due to its greater availability and ease of processing. The icons of the earliest Russian iconostases were simply painted over plastered wooden walls.

At the turn of the 15th century, iconostases began to enclose not only the central apse, where the altar was located, but also the side apses, behind which were the credence altar (prothesis), and the room for performing funeral services, later transformed into the deacons’ sacristy (skeuophylakion). Approximately in the 15th-16th centuries, the iconostasis grew in height, with several more tiers of icons added on top of it.

The modern multi-tiered Russian iconostasis took shape and became predominant only by the 17th century. Most often it consists of five tiers. The first (bottom) tier contains an icon of the church’s patron saint or the feast day to which the church is dedicated. It also includes the icons of the evangelists on the Holy Doors, the icons of the Lord and the Virgin next to the Holy Doors, and the depictions of angels on the southern and northern gates. The second tier, called the Deesis, signifies the prayer of the Church to Christ. The third tier contains icons of the church festivals. The fourth tier is dedicated to the prophets of the Old Testament, and the fifth – to the Old Testament forefathers.

The appearance, as well as the theological interpretation of a modern iconostasis is significantly different from that of the ancient altar barriers. Unlike its ancestors, used exclusively for practical purposes, it now forms a sacral space, serving as a symbolic boundary between “heaven” and “earth”, marking off the secular world from the sacred domain.

Holy Tradition says that Christ, His Apostles used curtains to seperate the Holy of Holies from the other space of the (house-) churches. This can still be seen in Oriental Orthodox Churches. It is not only for practical use but of mystical meaning. In the early church was arcan discipline. No one was allowed to enter the Holy Temple and to participate in the Holy Mysteries. And only priests and Hierarchs were allowed to enter the Holy Table. The Throne of Glory.

It is very sad that more and more often low iconscreens can be seen. In greece even a little wall. This is pure protestant spirit.

Christ has torn down the wall of separation between God and Man, why put it up again?

Do you mind to specify how exactly having an iconostasis builds up a wall between God and man?

(Reader John Malov)