Sometimes, for various reasons, traditional encaustic or tempera paints are not available to icon painters, prompting them to look for other suitable materials. Stone has proven to be easily accessible and quite suitable for icon painting. As a result, a wide range of stones, from simple boulders to noble marble and semi-precious or precious stones, began to be used for making religious icons.

Boulder Icons

Boulder icons are mostly quite primitive in artistic execution, but far from simple in technical implementation. All of the few known representatives of this type have been found on the territory inhabited by the Slavs, mainly Eastern ones. This type of icon remains poorly researched. It is not always possible to clearly determine who created such an icon, when and for what purpose. Naturally, no tradition of icon painting on boulders has ever developed, which makes each specimen unique and most commonly different in method of depicting an image. Some boulders have relief images without paint, while others are painted (some of the images below represent bolder icons with restored paint layers).

The most probable hypothesis about the origin of these icons states that they were intended for travellers, which explains their typical location not in settlements, but rather along the roads. This version is also supported by the fact that some boulder icons also had maps, indicating the locations of the nearest towns and villages.

Stone Icons

Stone, as a material for icon painting, has been endowed by a divine blessing, as evidenced by a number of not-made-by-hands stone icons, including the Savior of Edessa (544), as well as Zhirovitskaya (1470) and Pochaevskaya (1559) icons of the Mother of God.

Speaking of the hand-made icons, with the gradual improvement in their technology they began to enter everyday life and architecture. It is worth noting that the 13-16th-century specimens found in Russia (and a few more ancient items) are quite small. Most often, their size does not exceed 5×7 cm with a thickness of 0.8 cm. They come in about 20 repeating shapes, the most common of which is an elongated rectangle. The top, bottom, or sometimes both corners of these specimens are often rounded.

The material used for stone icons can be divided into three groups. Some were made from the softest stones like steatite and soapstone, others used relatively soft stones like limestone and marl. The third type represents the hardest varieties of sandstone.

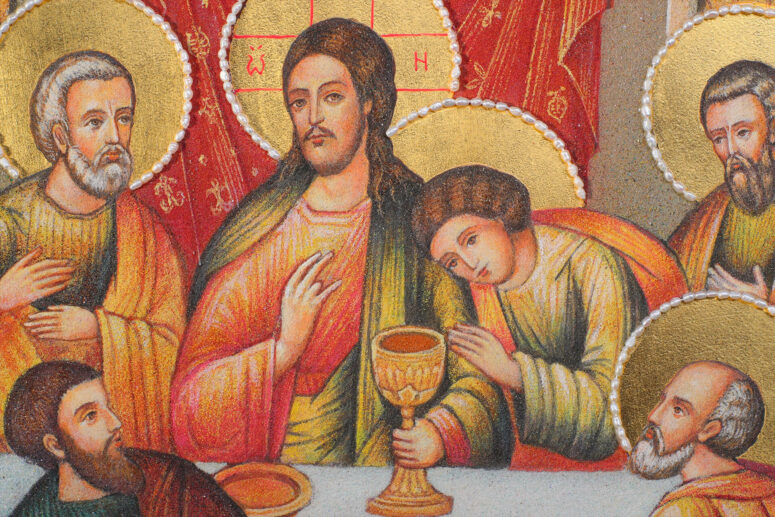

All of these groups featured relief images of saints, as well as episodes from Holy Scripture or hagiographic literature, depicted in stone. Most often, they represented a single image of a saint (commonly the owner’s heavenly patron).

The elements of these icons were carved in the stone, observing a particular order. First, the frame was applied, then the outline of the figures, then the background with the actual figures and finally, the facial images.

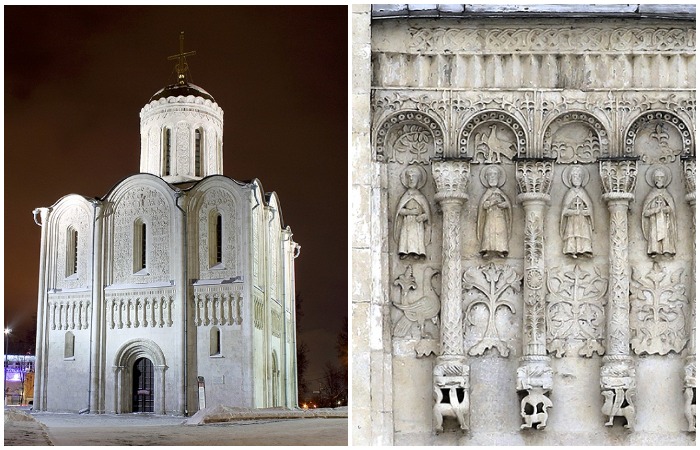

The new technologies, appearing over time, have simplified the manufacture of stone icons. Due to the technical complexity of making full-size stone icons, there are hardly any made, with a few exceptions, decorating the facades of rich cathedrals (for example, the Cathedral of St Demetrius of Thessaloniki in Vladimir).

Modern technologies greatly facilitate the process of creating a stone icon, allowing the use of a wide range of stones. For example, there are icons made of marble, granite and jasper.

Stone icons can be bold or flat. Both engraving and painting are used in the manufacture of planar icons. Relief icons are typically not painted.

Crushed Stone Technique

Colored stones are also used to make icons. Small gems (cameos and intaglios) are widely known to be used for applying images on them. Semi-precious stones as pigments for tempera paints are firmly embedded in classical icon painting. However, creating full-size icons entirely from natural gems was difficult to accomplish before icon painters began using crushed stones in their work.

The crushed stone technique comes from the Urals, although its roots can also be found in Florentine mosaics and even in Egyptian sand paintings. In the 17th century, the numerous deposits of gems, found in the Urals, began to be actively mined and processed. This led to a large amount of remaining stone chips, which were used in painting, and later in iconography.

The image is created using fractions of semi-precious and precious stones, ground in a mortar. The icon is graphically divided into zones, covered with glue and then with stone chips. The smallest fractions are used for distant views and facial images, while the foreground, decorations and clothing are made using larger grains.

The final result of using this method depends on many small factors, such as the air circulation in the room. It is difficult to predict exactly how the stone will adhere to the base. This makes it impossible to create two completely identical icons, which means that each icon made in this technique is unique in its own way.

The final image is bright and rich. A distinctive feature of such icons is a particular glow, produced by fractions of precious and semi-precious stones. Most importantly, such icons are very durable and do not lose their original qualities over time. This makes them an excellent candidate for becoming a family heirloom.