We imagine the church as a free-standing building with domes, a forechurch, an altar and multiple icons. But have the Christian churches always looked like that? As we know from the Book of Acts, worship services in the old times took place in private houses, typically belonging to the wealthiest parishioners. These buildings looked usual from outside but underwent some major alterations inside to serve as places of worship. Let us consider one example of such an old church, known for its unique frescoes. It was discovered in the early 20th century in modern-day Syria.

Historical background

In the 1920s, the British military was upgrading the fortifications in a Syrian desert as they stumbled across the ruins of an ancient wall with some well-preserved frescoes. The wall turned out to be a fragment of a castle of an ancient castle city on the Euphrates. The site became known among historians and archaeologists as Dura-Europos. This discovery provided researchers with insights into the appearance of early churches and the early development of old Christian church art. Today, fragments of this old city can be found only among museum exhibits. The ancient city was almost fully destroyed in the Syrian civil war of 2011.

During the excavation at Dura-Europos, archaeologists have discovered the ruins of a synagogue, a Christian church and several Pagan temples located a short distance away from each other and dating back to the third century AD. The high concentration of religious buildings catering to members of different faiths suggested that the old city had a diverse population. Assyrians, Arabs, Jews and members of several Iranian tribes formed its majority. However, the city’s rulers were of Greek and Macedonian descent, and the city itself was governed in the Greek tradition.

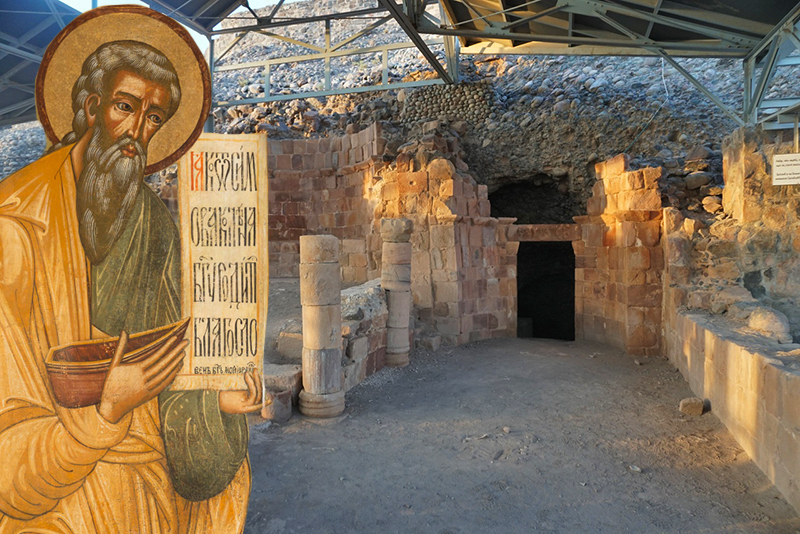

Of interest to us is this private house from the year 232 used as an early domestic church.

Floor plan and the frescoes

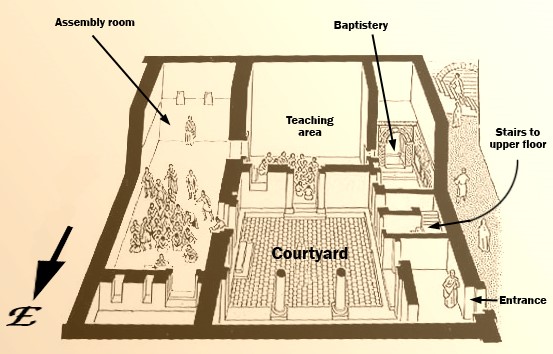

The building’s interior design changed in a major way. A large auditory for seventy people appeared in its southern wing, where the faithful congregated for joint prayer and the sacraments. Adjacent to the hall was a smaller room, presumably a teaching area for catechumens and children. In the North-western wing was a baptisterium with a baptistery. In the centre was the inner courtyard with doors to every other room. The second level of the building had not survived.

The best-preserved fragment is the baptisterium. It is also the only element of the church with frescoes. Above the rectangular baptistery is an arc-shaped valley. Its façade was painted with a floral ornament, and on the inner surface were the images of stars in a blue sky. The frescoes on the walls depict a variety of biblical stories and rank among the oldest and best-known monuments of early Christian church art.

Surviving to our times are some of the following known biblical characters: Adam and Eve in Paradise, the Good Shepherd, Jesus and Peter walking on water; procession of the Myrrh-Bearing women, healing of the paralytic, and Jesus’ encounter with the Samaritan woman. Because only some of the frescoes have survived, it is not possible to conclude with certainty if they were a part of a single narrative.

The controversial fresco

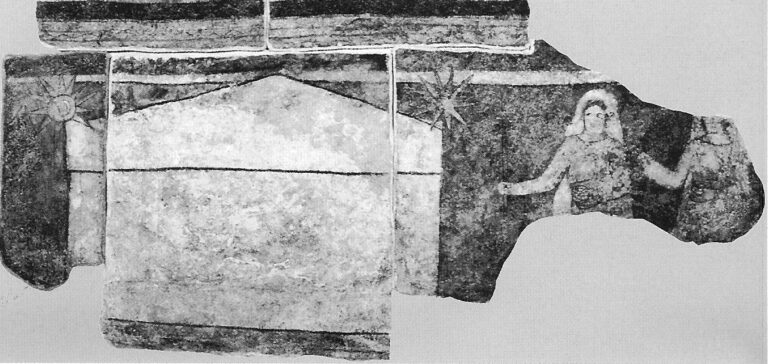

The fresco with a young woman at a well is the subject of some controversy.

In the 1930s, few scholars had any doubts that the woman in the frescoes was a Samaritan. Clark Hopkins, leader of the team of archaeologists at the Dura Europos site, suggested that the image could be the left fragment of a larger fresco, whose right segment, depicting Christ, may have been lost. Later, he accepted the idea that the Samaritan woman could have been depicted without Christ. Referring to the example of the wall paintings in the catacombs of Rome, he supposed that in the early years of the Christian church, it was common practice for artists to depict only one character and let the viewer recall the rest.

The first scholar to question these hypotheses was Michael Peppard, a student of early Christian architecture and iconography of the Roman empire. Eight decades later, he joined the research effort at the Dura Europos site and offered an alternative explanation. He hypothesised that the mural was too small for the depiction of Christ, and there was no tradition in church art for depicting the Samaritan woman without Christ. Referring to other examples of Western Christian art and Eastern Christian iconography, Peppard proposed that the fresco showed the Annunciation of the Mother of God. He referred to a tradition of depicting the Mother of God hearing from an angel the good news of the Saviour’s conception standing at a well.

The depiction of Mary at the well is based on the apocryphal text of the Proto-gospel of James from the second century. It has been present in the Russian iconographic tradition, in which Mary is often shown with a spindle and a red thread. Although the Proto-gospel of James was never included in the biblical canon, it remained widely known and used in Eastern Christianity, including in Byzantine.

In light of these facts, Peppard’s hypothesis seems fully plausible. If Peppard is correct, the location of the oldest known image of the Mother of God may not be the Catacombs of Priscilla, as previously believed, but the domestic church of the early Christians at Dura Europos.