In the previous article on church structure, we briefly talked about the exarchate, as the lowest level of church self-government, not including, of course, the basic diocesan level. In this article, we will discuss the concepts of autonomous and self-governing churches.

Ancient Metropolises

In the Byzantine era, when church structure gradually began to acquire its familiar outlines, the metropolises were the intermediate link between the diocese and the Patriarchate. Metropolises began to take their shape before the introduction of exarchates and patriarchates. They had a high level of independence, being autonomous, i.e. independent from other similar metropolises. However, according to the established ancient tradition, metropolises respected the authority of the great Churches of Rome, Alexandria, Antioch and Ephesus.

The very term “autonomy”, like many other concepts related to the social order, came into church use from civil law. According to Roman law, the right of autonomy was enjoyed by some local organizations, for example, by priestly colleges. Church autonomy has acquired a similar significance.

The Autonomous Church (Greek Αὐτονομία – “self-law”, something governed by its own laws, independent) can be defined as a local church, which has received from the Mother Church (the Kyriarchal Church) sufficiently broad rights to self-government in its internal affairs. Exarchates or even simple dioceses have enjoyed autonomy earlier. The right of autonomy can be granted not only to entire local Churches, but even to simple parishes and monasteries. This practice was especially common in Athos (for example, the Hilandar Monastery, enjoying, according to the Typicon of St Sava, almost complete independence from the Holy Synod (Kinot) the main cathedral governing body of the Holy Mountain.

Dependency on the Mother Church

The dependency of an autonomous church on the kyriarchal church, which is often (although not always) the same as its mother church (i.e. the church that gave birth to it) is manifested in the following rules:

- In contrast with an autocephalous church possessing the fullness of ecclesiastical independence and appointing its own bishops (including the primate) an autonomous church lacks such a level of independence. Despite the right of an autonomous church to choose and ordain its bishops or its primate, the latter has to be approved by the head of the kyriarchal church (autocephalous church, which embodies that autonomous Church), who also performs the ordination of the primate.

- Ecclesiastical rules of an autonomous church are approved by a council of the kyriarchal church; the head of a church autonomy is subject to the court of the highest judicial authority of the kyriarchal church. In the churches of the Russian tradition, the name of the kyriarchal church’s ruler (kyriarch) is remembered in prayer before the names of the autonomy’s primate and the diocesan bishop. In Greek churches, only the ruling bishop is commemorated during services.

- Another interesting rule, signifying an autonomy’s administrative and even sacramental ecclesiastical dependency on the mother church, is the exclusive right of the kyriarch to confer the holy Chrism, used during the Sacrament of Chrismation, without which full church membership is impossible. Let us note however, the sometimes conventional nature of this rule, illustrated by the fact that some autocephalous churches (for example, the Churches of Hellas, Poland and Albania) receive holy myrrh from Constantinople, which was particularly stipulated when Tomoses of autocephaly were granted to these churches. This fact, however, is interpreted not as a kind of canonical dependence, but rather as an expression of brotherly love and respect for the “first among the equal” churches.

Grounds for Granting Autonomy

The main reason for granting autonomy to a church is most often its location outside the state in which the mother church is located. Other important reasons may include a geographical remoteness, as well as ethnic or linguistic uniqueness of a particular church autonomy. Historically, obtaining state independence by a country has often been followed by quickly granting autonomy status to the church communities located in this state.

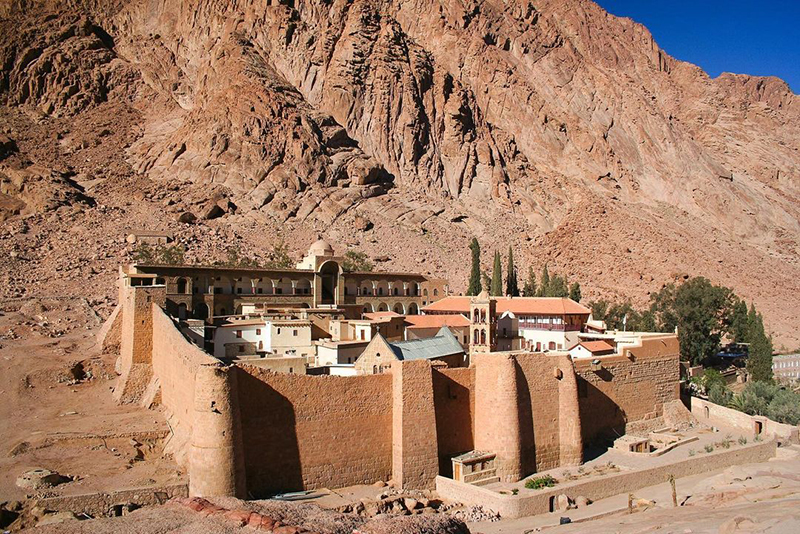

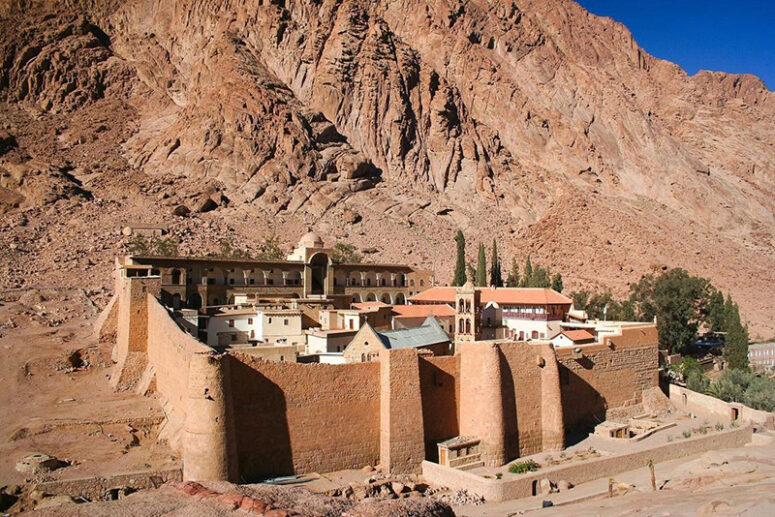

Currently, there are several autonomous churches in the Orthodox Church, among which are the Finnish, Cretan, Estonian Churches (Ecumenical Patriarchate), the Japanese Church (Moscow Patriarchate) and the American Archdiocese (Antiochian Patriarchate). The Sinai Church is another example of an ancient autonomy, notably consisting of just one community (Monastery of The Great Martyr Catherine) and headed by one bishop, ordained by the Patriarch of Jerusalem. Autonomous churches should be distinguished from such a fairly new ecclesiastical phenomenon as self-governing churches, which, while not being de jure autonomous, also enjoy certain independence. These church structures include such Churches as the ROCOR (part of the Moscow Patriarchate, but with full autonomy in internal affairs), the Churches of the Baltic countries and Moldova, as well as the Church of Ukraine (all within the Moscow Patriarchate, with broad autonomy rights granted to the Church of Ukraine).

Now that we have briefly looked into the ecclesiastical self-government structure at the level of exarchate and autonomy, we have come to grips with the concept of church autocephaly, which we will focus on in our next article.