There are many councils in the history of Orthodoxy. Seven of them are called Ecumenical for their indisputable authority for the entire church. Other councils have been held, whose scale and significance could be determined as “local” and whose decisions were important mostly for the churches that held them. In this article we will discuss some of those “minor” councils, which, despite not being ecumenical in the fullest sense of the word, have been approved and assimilated by all the patriarchs and have high authority for all Orthodox Christians.

Council of 1089

This council was held in Constantinople in relation to Pope Urban II sending his emissaries to Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. According to Goffredo Malaterra, who was a contemporary of these events, Urban II, after his accession to the Roman throne in 1088, decided to send Abbot Nicholas from the famous Greek monastery of Grottaferrata and Deacon Rogerius to Constantinople. The ambassadors were supposed to express “paternal reproof” to the Basileus for forbidding Latin Christians living within Byzantium to serve the liturgy on unleavened bread (Malaterra Gaufredus. Historia sicula // PL. 149. Col. 1087-1283). However, from the emperor’s response we see that in all likelihood the delegation’s main motive was the desire for “peace” and “harmony” between the two churches, as well as renewing the tradition of commemorating the Pope during divine services in Byzantium.

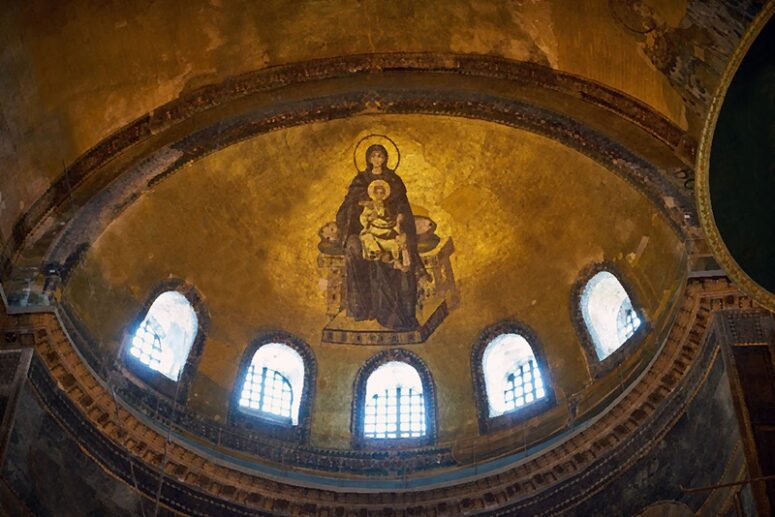

The emperor called upon the Patriarchs of Constantinople and Antioch, as well as some twenty metropolitans, to convene a Council and jointly discuss a program of action in regards to the communication of Urban II. The fathers recognized the existence of a schism between the Eastern Churches and Rome, but at the same time noted that the separation of the Roman Church from the rest of the four patriarchates did not take place as a result of any conciliar decision, and therefore is canonically unjustified. In that context, at the insistence of the emperor, the hierarchs agreed to renew the commemoration of the Roman primate, but only after receiving a “sound” confession from him. That confession was also supposed to contain approval of the canons of the Quinisext Council (691), which was much more problematic, since the canons of that Council were not recognized by Rome even in the times of unity between the East and the West. Also, the Pope was to send his legates in order to settle controversial canonical issues.

Along with the reciprocal epistles from the emperor and the patriarch, an envoy was sent to Rome from the Antiochian Church, which was to enter into negotiations on restoring the unity of the Churches. However, in all appearances, the Eastern churches never received the awaited confession of faith by the Roman Primate. The era of the Crusades began and the question of reuniting Christians receded into the background.

Council of 1484

In 1453, the Turks put an end to the existence of the Eastern Roman Empire, and in doing so completely nullified the results of the Council of Florence, held shortly before the fall of Constantinople. The Florentine union, formed between the Catholic Rome and the Orthodox East in 1439, was never brought to life, since the opposition to it began immediately after its signing. The anti-union position of the Greek clergy and laity was led by St Mark of Ephesus, while the 1443 Council, held in Jerusalem condemned the union and, thereby, opposed the position shared by the Patriarch and the emperor of Constantinople. The Turks also banned the union, but their policies were based on their geopolitical interests.

Only 45 years after the signing of the Florentine agreements, the non-canonical nature of the Council of Florence was officially recognized, and its decrees rendered invalid. It happened at the Council of 1484 in Constantinople, which was also attended by representatives of the Alexandria and Jerusalem Patriarchates. Rather than declaring invalid the Council in Florence, the main task of the 1484 Council was to determine the rite of accepting Catholics into the Orthodox Church.

That question was very relevant at that time, since the Turks seized more and more territories, previously subordinate to the West (for example, the Duchy of Athens), and many Christians returned under the omophorion of the Patriarch of Constantinople. Additionally, the Turks endowed the Patriarch of New Rome with secular power (the powers of the ethnarch of all Greeks and bearers of the Greek faith), so all Christians of the empire, even those previously under the pope, were now subordinate to him.

The Council decided it sufficient for Catholics, wishing to become part of the Orthodox Church, to renounce Latinism and undergo chrismation (at present day, some Churches practice accepting Catholics through confession if they have previously passed confirmation). The Great Moscow Council of 1667, which also decided to accept Catholics through the second rite (i.e., through chrismation), also makes reference to the Council of 1484, revising the decision of the 1620 Council to re-baptize the Roman Catholics.

From the example of these two councils we see that the conciliar life of the Orthodox Church did not seize even in the second millennium. The Council of 1089, despite the absence of any significant results, testifies that the Eastern Patriarchs were ready for dialogue and the restoration of communion with Rome. The Council of 1484, overriding the acts of the Council of Florence, which failed to become a platform for a full-fledged dialogue between the Catholic and Orthodox Christians, took a moderate position regarding accepting Catholics into Orthodoxy.