Christianity came to Africa as early as in the 1st century after Christ. It was preached in this part of the world by three apostles: Philip, Matthew, and Mark. For a long time, Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) remained a center of Christianity, after adopting it as the official religion in 330. Its Christians have preserved their Orthodox faith despite countless attacks from the Muslims and Western colonization. Ethiopia’s location in mountainous and hard-to-reach terrain limited external influences on its church art. The Christians of nearby Egypt were in a different situation: they were far more open to historical upheavals and religious developments, and their churches were built along key caravan routes to Palestine and beyond. They were also living amid Muslims, and nearly all converted to Islam by the 7th century. The isolated conditions of Ethiopia were highly conducive to the formation of a distinct Abyssinian painting and iconographic tradition.

In general, Christian church art in Africa was shaped by the traditions of the early Coptic Church of Egypt, and the church history of ancient Abyssinia and Ethiopia.

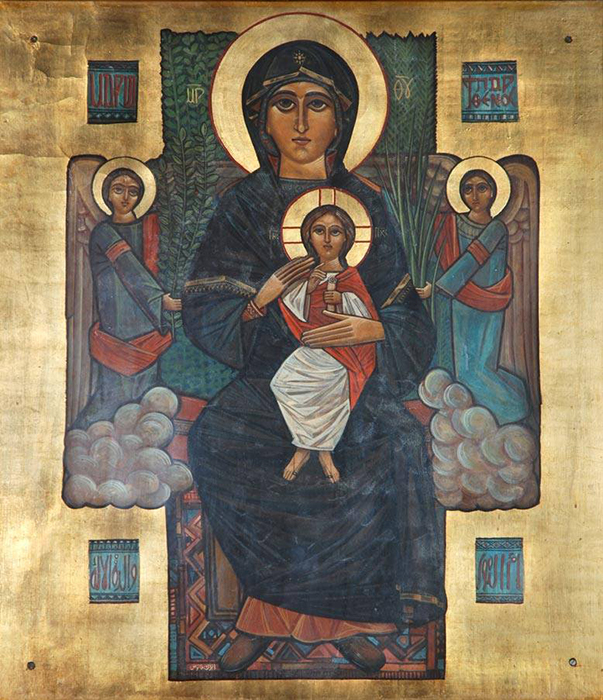

Coptic icons

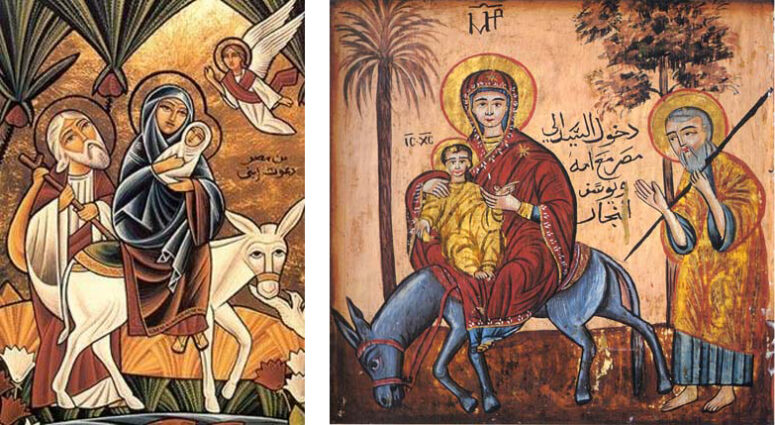

Coptic church art was greatly influenced by the art of ancient Egypt, with some input from the old Hebrew and Greek painting schools. Many Coptic Christians believe that iconography originates from Egypt, and refer to visible similarities of the iconographic canon with Ancient Egyptian artworks.

Characteristic features of the Coptic style are visible in the icons dating back to as early as the fourth century. Large eyes, clear lines, sharp edges, joy-filled and peaceful faces of the saints, the air of innocence and child-like features of the images are some of their hallmarks.

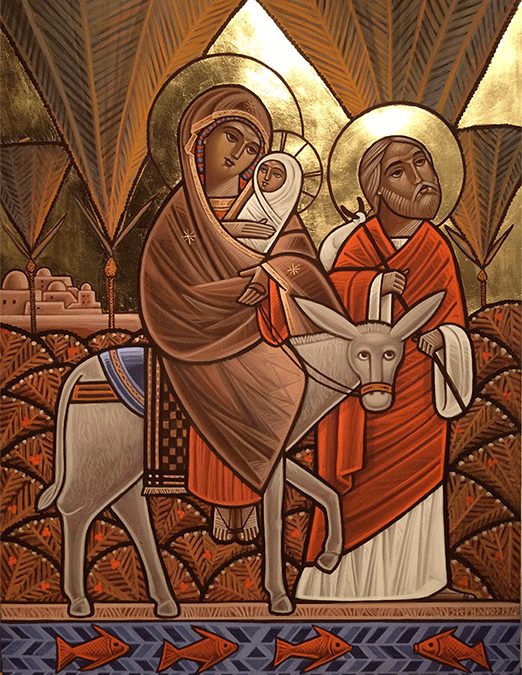

The saints depicted in the icons do not look at the viewer, but beyond and past him. This feature is also common to many old Ethiopian icons. Not surprisingly, the flight into Egypt was the most common biblical story depicted in the icons.

The Arab conquest of Egypt in the 7th century impacted the iconographic tradition, while the near-universal adoption of Islam in Egypt interrupted it for many centuries.

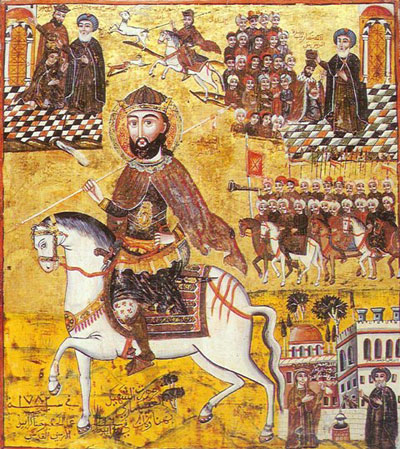

Coptic Christianity and the practice of venerating the icons resumed from the mid-18th century. One of the best-known church artists of the time was Yuhanna al-Armani. His works feature some advanced techniques and innovative approaches, such as the use of several storylines in a single narration.

From the mid-1960 the Coptic traditions of iconography were succeeded by the neo-Coptic school.

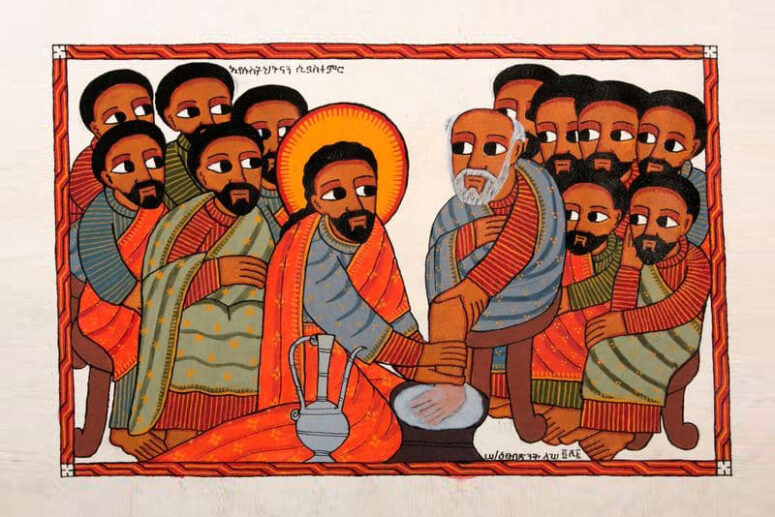

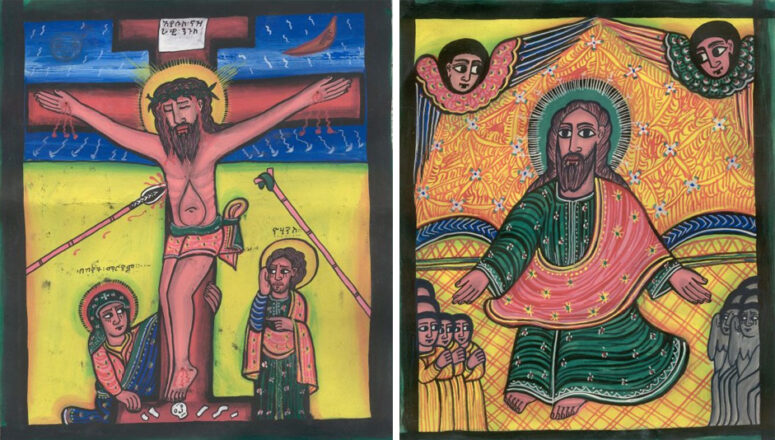

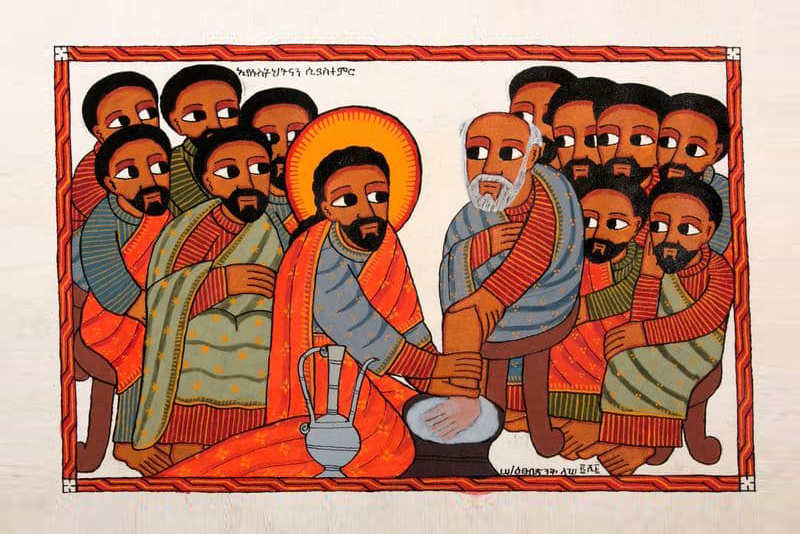

Ethiopian Orthodox icons

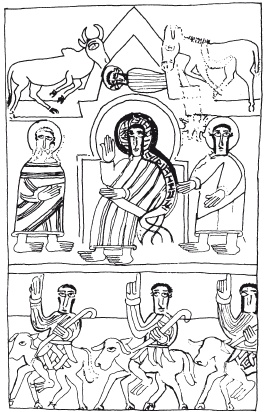

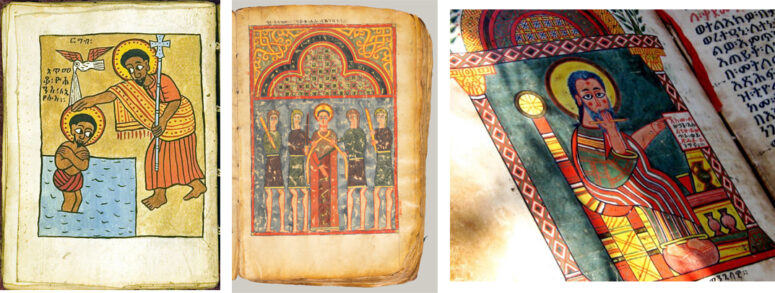

The first examples of the Ethiopian tradition of church art were the illustrated gospels, translated into the local language approximately in the 6th century. The ancient manuscripts were brought from Palestine and Greece. The first Abyssinian artists copied these richly illustrated books and replicated the depictions of the biblical stories in their distinct style. Abyssinian art is known for its simplicity of colour and design.

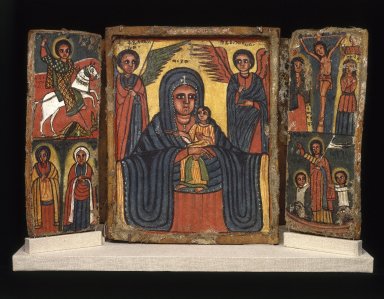

The rise of the iconographic school in Ethiopia occurred in the late middle ages, at around the 15th century. The ruling emperor Zara Jacob had just learned about the tradition of the veneration of the icons and mandated universal adoration of the Theotokos and display of her icons in worship services and popular feasts. The Ethiopian iconographic style – distinct among the other traditions of Christian iconography – was thus established.

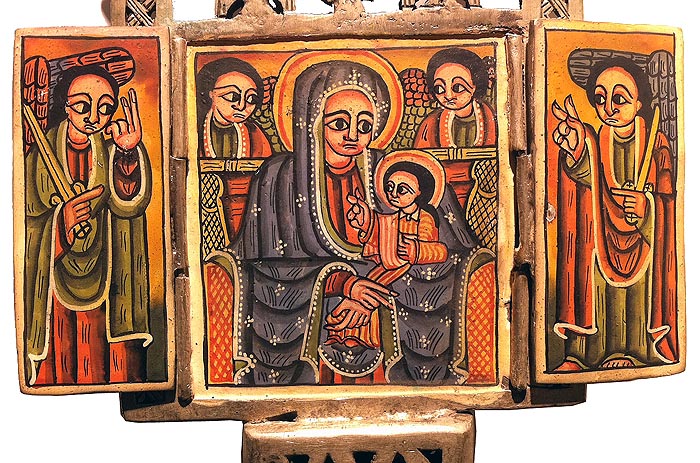

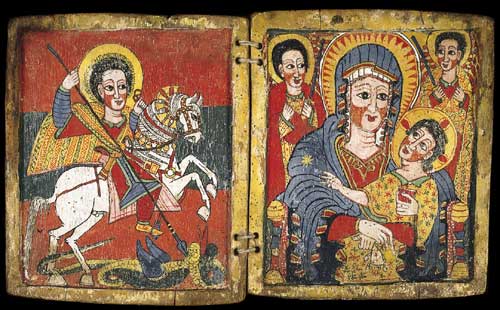

Many icons were created as double or triple tablets, connected physically and thematically. Smaller wearable versions of two-tablet icons were available.

In Ethiopia, there is a strong tradition of venerating the Theotokos. The Mother of God is commemorated 33 times in the liturgical year and is depicted in the majority of the icons.

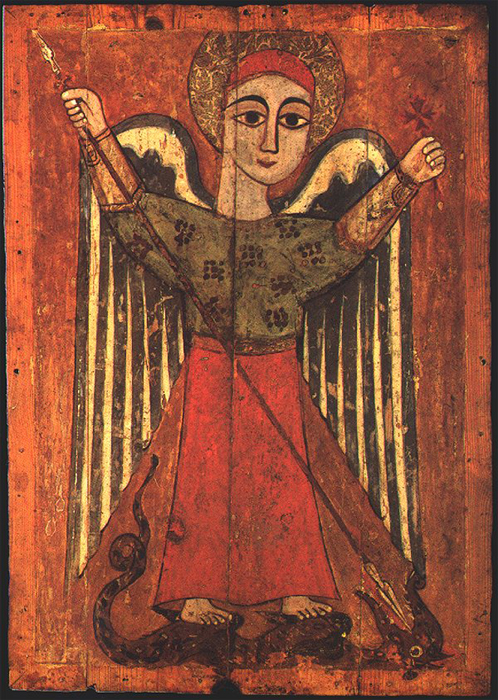

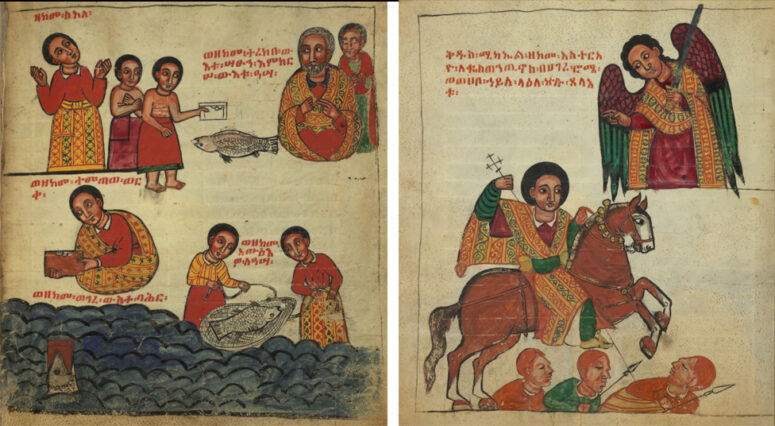

The 17th-century works of the school of Gondar (the seat of the Ethiopian emperor and government) are remarkable examples of the Ethiopian tradition of church art. Some notable representatives of the school that have survived to this day are 49 colourful illustrations to a manuscript on the miracles of Archangel Michael with liturgical readings. The illustrations depict the Lord, and the Archangel performing the miracles.

Some typical features of the Gondar style include an uncoloured background, clear boundaries of the images, painted in black lines, and the use of elementary colours (mostly yellow, green, red or blue). The artists make visible attempts to depict the shades and volume. Perhaps the red blots on the faces noticed in the icons of the 17th centuries is also a technique for livening up the images.

The Ethiopian iconographic tradition changed little from the 18th to the 20th century. Similar to Coptic iconographers, the iconographers of Ethiopia have tended to combine several narrations in one icon.

Modern painters and iconographers of Ethiopia have continued to pursue and build upon the old tradition.

* The Ethiopian church is an Oriental Orthodox (“non-Chalcedonian”) Church, similar to the Coptic, Syrian and Armenian Orthodox churches; it preaches ‘monophysite’ Christology; it recognizes the decisions of the first three ecumenical councils, but not the canons of the Council of Chalcedon (451).

** Abyssinians – the old name of the inhabitants of Ethiopia (formerly, Abyssinia).

Thank you for sharing this wonderful and insightful article about Coptic and Ethiopian iconography.

Thank you for reading and the comment!

I am surprised that you do not credit the icon of the Theotokos at the beginning of your article. You have “borrowed” it from the website Full Homely Divinity. I know it is the same icon because of the imperfections which would be impossible to match exactly. It is used as an illustration on a page about icons in Anglicanism. If you had asked, I would have told you where and when the icon was written as it belongs to me.

Thank you for telling us where is image from. Sorry for our poor attention to details.

Good job, Anastasia!

Thank you for reading and the comment!

Thank you for sharing this short and detailed histograph of Coptic and Ethiopian Iconography.

I wish to add that even though Ethiopian and Coptic church preach ‘monophysite’ Christology; a more accurate understanding of Oriental Christology is “miaphysite” Christology. Both Eastern and Oriental churches agreed in Geneva 1990, that “In the light of our agreed statement on Christology…, we have now clearly understood that both families have always loyally maintained the same authentic Orthodox Christological faith, and the unbroken continuity of Apostolic tradition”

Thank you for the comment and the detailed clarification!