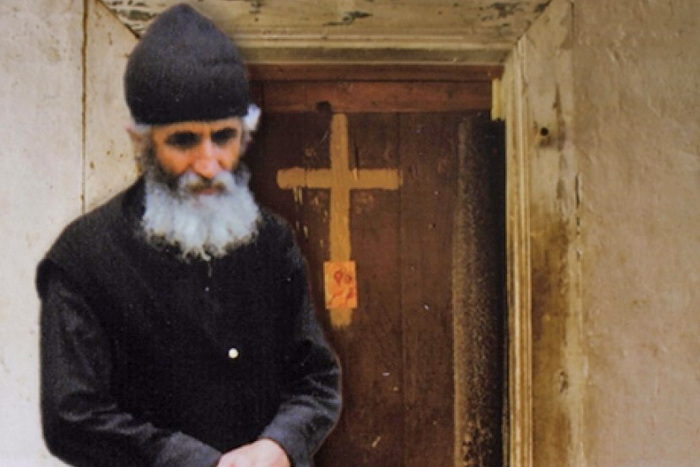

The path to Athos is open to men only. But in Greece there is a women’s monastery where they live according to strict Athonite rules and serve without electricity, by candlelight. This monastery, in the village of Souroti, was founded by Elder Paisios the Athonite, whose books have been so popular in the past few years in America and Russia. A correspondent of the Russian Orthodox journal “Neskuchnii Sad” headed to Souroti to meet with people who remember Elder Paisios.

“I Was an Atheist”

“When Elder Paisios would visit the sisters at the Monastery of John the Theologian, thousands of people would come see him. I went especially to see how the swindler was cheating them all. I was an atheist. This was in 1988. The service had started. The church was divided into two parts: for laity and for nuns. There was a taut rope between the two sections, and I didn’t know that I couldn’t go in, so I crossed over. There was an elder sitting among the nuns, whose face radiated light… Seeing this, I left, but two days later I came again, for a blessing. Then I went to Athos and so remained with the elder for life,” recalls Nicholas Mentesidis, a jeweler who knew the elder.

There are many such stories, of when the first, and sometimes the only encounter with Elder Paisios changed somebody’s life. They talk about it especially often in Souroti, a quiet village outside of Thessaloniki. “Many who knew the elder have moved here—closer to the monastery,” claims local postman Polikletos Karakatsanis. “You would think in vain that everyone in Greece is a believer—statistics say otherwise: only two percent of the ‘Orthodox’ regularly commune. We try to live close to one another, holding onto God and one another.”

On the road to Souroti, they sell small church-chapels, as tall as a man (like our cabins or baths). You can buy thse chapels and put them near your house or in your olive grove. Judging by their number, there really are many believers in the surrounding villages. “Fr. Paisios told me,” recalls Athanasios Rakovalis, the author of a book on the elder, “that to avoid sin in our difficult times, we must hold fast to the Church. The farther away, the more people will be lukewarm: The people are divided—those who leave the Church go far, but those who remain with God will be zealous.”

Zealots

For the residents of Souroti, the nuns of the Monastery of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian serve as a model of zeal. More than half of the sixty-seven sisters well remember Elder Paisios. He helped them write their monastic rule and spiritually guided the monastery. The answers to questions, published in Elder Paisios’ books, were addressed precisely to these nuns.

The nuns avoid communication with the outside world, and don’t give interviews. It’s no accident. Elder Paisios is greatly popular in Greece, and some unscrupulous politicians and journalists use his authority, distorting the elder’s words to their benefit, to give weight to their ideas. “Moreover, Geronda believed,” says one of the older nuns, “that any participation in secular life, including communication with journalists, can hurt us.” The elder wrote, “If a monk is constantly occupied with external things, then he will unavoidably go wild spiritually and not be able to sit by himself in his cell; even if they bind him, he’ll always like to talk with people, to lead excursions, talking about the domes and the archaeology, showing them the pots with various colors, and making them meals.” “We do share our wealth though,” the nuns emphasize, “by publishing the notes of our conversation with the elder and his letters!”

They distribute books on the elder, printed in various countries, in various languages, to inquisitive pilgrims to read. The library is in the guest house, in a special room for meeting guests. There, settled in with a book on a bench, you can have a cup of coffee and try some sweet loukoumi. Treating guests with loukoumi is an ancient Athonite tradition which they also follow in Souroti. They say that in less populated monasteries, they put out a jar of sweets and hide in their cells, thus fulfilling their duty of hospitality, but not meeting with tourists.

Filthy loukoumi

There’s a large olive tree growing near the path to the church. On Sundays and feast days, one of the older nuns holds a conversation in its shade with the visitors. They usually sit around in a circle on some stumps and ask the mother some questions or listen to her stories, and sometimes recollections of the elder.

Fr. Paisios often spoke with pilgrims just the same way, on the benches. When the elder would visit Souroti, although he would try to hide the time of his arrival, many people would come—cars were parked in the neighboring village of St. Paraskevi, two kilometers away. “After speaking with the elder, people would feel peace and comfort in their souls,” says Athanasios Rakovalis. “Many smelled a sweet fragrance during these meetings; many, and even I myself, have seen his face shining; but it’s not people that have glorified the elder, but the Lord Himself.” For instance, Souroti resident Kaliopa tells a story: “My friend and I went to see the elder. When our turn finally came, he was so tired that he couldn’t even speak. We silently approached, and the elder blessed us with some crosses: He gave me five—my family has five people, and to my friend he gave four—her family has four people. And we didn’t even say anything!”

“One day I realized I was asking the elder something I had already asked, because I couldn’t remember the answer,” recalls Athanasios Rakovalis. “Then I started recording the conversations in a notebook. People found out I was gathering recollections to publish them, and they began telling me their stories. For example, one man had filmed an amoral film and was living in luxury. Someone told him about the elder, and having decided that the elder was a charlatan, he went to Athos to confront him. When he entered the kalyvia, the elder treated his guests with loukoumi. He gave everyone a piece, but in front of this man he threw the loukoumi on the ground and said, “It fell. Pick it up and eat it.” Of course, the man was offended. “How am I going to eat that off the ground—the loukoumi is filthy!” The elder answered, “You also feed people with filth.” The man was so shocked that he ran out of the kalyvia, but the next day he returned and spoke with the elder alone. The elder told him to quit his dirty work, and so he did, and now this man is a pious Christian.

The elder was never angry and never irritated. If someone tried to anger him, he would say he had a headache or some obligation and leave, so as not to offend anyone. But one time he got seriously angry at me. I went with a friend, and we wanted to stay and sleep in the elder’s yard. It started to rain, and I dared to ask the elder to pray that the rain would move. The elder drove us both out of his kalyvia with the words, “Who are you to know God’s plan? If God is satisfied with rain now, it means the rain is needed now—what a big responsibility to care for the whole earth and to arrange rain at the necessary time! And what kind of plan do you have? You say, ‘I want,’ and don’t think about anything else?” However, when we left the kalyvia, I turned and saw that the elder was blessing us with the sign of the cross.”

How not to sleep

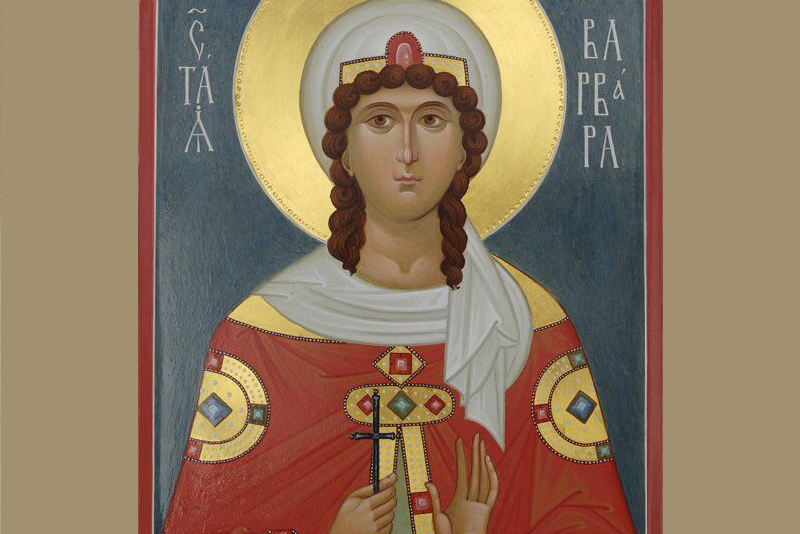

In the guest housing, where I was staying, there were five young girls (men could not stay on monastery territory). Three cheerful girlfriends, students of the pedagogical university in Thessaloniki, Evangelia, Barbara, and Anna, often came to the monastery on the weekends “to pray and get some rest from the big city.” All three were planning to eventually get married, but they loved the monastery life: They went to the services and looked for obediences “to help the sisters.” Two other girls, Elena and Christina, came individually and were very quiet, and would pray for a long time in their rooms—they were obviously inclined towards the monastic life.

“I fall asleep during the long services,” Barbara honestly confessed, “but if I don’t go to church at all, what’s the point of coming here? Although I know how not to sleep—you have to stand on your feet the whole time. It’s hard, so I sit in the stasidia, and… fall asleep.” They serve on the new calendar in the monastery, as everywhere in Greece, but according to the Athonite rule, without electricity, with candles, and they serve the full services. In the morning, the services begin at 4:00 and end at 10:00. However, there isn’t always Liturgy. It’s served by priests invited from Athos only on Sundays and feast days. Many commune at Liturgy, although, as is customary in Greece, without Confession. Confession happens in the monastery at individual times. The spiritual life of the community follows the gerontissa, who hears the sisters’ revelation of thoughts and determines how often they should commune.

The evening service is short, except when the All-Night Vigil is served, which literally lasts all night. But usually the services go from 5:00 to 8:00 PM, including an hour break for dinner, as on Athos.

The monastery church is divided by a rope. When there are too many parishioners, the nuns, not at all annoyed, condense and move the rope closer to the altar, so it wouldn’t be too crowded for those who come. Women stand on the left and men on the right. The women don’t have head coverings but they are always in skirts; if you come in pants you can get a skirt at the entrance to the monastery—it’s a rule commanded by Elder Paisios.

There are stasidia along the walls of the church, but no rows of cushioned chairs, which is usual for Greek churches (just folding chairs for the infirm). “For the Greeks, the church is like one of the rooms in their house,” says one observant pilgrim from Russia. “On the one hand, he feels the need for it and his responsibility for it, but on the other hand, ‘at home’ he usually wants it to be comfortable and easy: pants, chairs, short services.” But Elder Paisios strictly denounced any kind of “Church comfort:” “If every monk had his mama near, taking care of him, of course it would be a comfort,” he wrote to the sisters. “And if we put a tape recorder in the church to play the sounds (prayers), then, of course, it would give us rest, and it would be an even greater rest if the stasidia were turned into beds. And no doubt, it would be nice for the ascetic if he had a little machine specifically for moving around his prayer rope, and a doll-ascetic who would fall and get up, doing prostrations for him, and he could buy himself a soft mattress, to lie and give some rest to his suffering flesh. Of course, this all brings relief to the flesh, but the soul is ravaged and becomes unhappy, leaving it only with feminine emotions and disquietude.”

Trapeza—part of the service

The nuns eat only twice a day. The pilgrims have an easier life: They are offered an additional light breakfast after the service, then also milk and cookies in the afternoon, and also little things like coffee and loukoumi, and you can take this whenever you want throughout the whole day. The monastery trapeza, painted with frescoes like a church, is located in the sisters’ building. First the nuns go, and then the guests are seated in the appropriate places.

Meals consist of one main dish (cooked beans, boiled grains, or pasta) and appetizers (olives, cabbage salad, feta cheese). The dishes are made of metal. Everyone gets another small plate for extra food if the portion isn’t big enough for you. For drinks, there is a pitcher of water—there is no coffee or tea anywhere. They don’t drink Greek coffee at all, except when they’re sick with a cold, for which they usually even sell it in drugstores. For dessert there is fruit, honey, and oriental sweets—all divided into portions.

The local pastry chef is very talented—Greeks love sweets. A box of sweets from a good confectionery is received as a valuable and welcome gift. “Once, when I was with the elder, fifteen young people came to him at his kalyvia,” says Nicholas Mentesidis. “They brought some oriental sweets with them as a gift for him, each in a big box. The elder, as soon as he saw them, not letting them in the yard, told them to exchange the boxes and receive them as a blessing from him: “George, give to Demetrios, Demetrios to Kosta…” he directed. Then he made sure that every last piece of candy was eaten, and said, “Why did you all bring me something I don’t need, so I had to take care of it?”

During the meals, one of the sisters reads the lives or teachings of the saints from a special high cathedra, which they call an ambo here. “The reading depends on the situation in the monastery; we read whatever is relevant for the community at any given moment,” says one of the older nuns. The reading ends at the ringing of a bell, everyone stands, they pray, and the pilgrims leave first. “During trapeza, everyone bears in mind that the service hasn’t ended,” explains one of the nuns, “therefore the general mood is not relaxed. Trapeza is not a rest after the service, but part of it.”