The principles of monasticism are deeply embedded within the scriptures. The call to monasticism is twofold. It represents a call to adhere strictly and without compromise to the commandments of God. It also represents a call to asceticism, to the sacrificing of material goods in this world in favor of spiritual goods in this world and the world to come. Ascetic practices are performed by figures throughout the scriptures, in the form of fasting and prayers and vigils. There are also, however, individuals called to whole lives of consistent asceticism, both as individuals for the benefit of their communities and communities as a whole. The first person whom we see receive a monastic calling, a calling received before his very birth, is Samson. In regard to carrying out and fulfilling his calling, however, Samson is shown to be a complete failure. It is important to separate the way in which Samson is portrayed and described in the scriptures from the way in which he has been portrayed in various popular media and Sunday School lessons which have sought to remake him into a sort of Judeo-Christian Hercules. There are resonances between his story and those of various ancient Mediterranean heroes described in epic literature. The scriptures, however, view the man and his exploits in very different, un-heroic terms.

The first sign of trouble in the Samson story is his family of origin, which comes from the tribe of Dan. The Danites were far and away the most wicked of the Israelite tribes. Rather than settle in the land granted to them by Yahweh following the conquest, they carried out a massacre in the city of Laish, conquering it and renaming it Dan (Jdg 18). After the massacre they established a center of idolatrous worship there with a line of priests descended from Moses serving at the shrine. Later, Jeroboam son of Nebat would place one of his golden calves there to make it a religious center of the official religion of the Northern Kingdom. Though these events are narrated after the story of the life of Samson, they are prophesied in the Torah (Gen 49:16-18). These events had, at any rate, taken place before the composition of the book of Judges, giving Samson’s origin its full resonance. Dan as cursed has a typological relationship with Judas among the 12. In the book of Revelation, Dan is omitted from the list of the tribes of Israel in the life of the world to come (Rev 7:4-8). Based upon these themes, St. Hippolytus and other Fathers identify Dan as the tribe of the antichrist.

Samson’s birth is predicted by a visitation by the angel of the Lord. This visitation to his parents before his birth is paralleled by St. Luke’s description of similar visitations to the father of St. John the Forerunner and the Theotokos (Luke 1). The parallel is particularly close to that of the visit to St. Zachariah, in that both Samson and St. John were to be Nazirites dedicated to Yahweh the God of Israel from their mother’s womb (Jdg 13:4-5; Luke 1:15). The Nazirite vow is described in the Torah in Numbers 6. Someone could undertake this vow for a period of time or for a lifetime. The Nazirite engaged in various ascetic practices for the duration of the vow. These can be organized under three heads. First, the Nazirite drank no alcohol and under this head came general abstention from gratifying the pleasures of the flesh, even those which are not themselves blameworthy. The second was a vow to never shave or trim the hair, under which heading comes a lack of concern for appearance and vanity. Finally, the Nazirite was to preserve himself in a state of holiness which included ceremonial cleanness, understood under the head of never coming into contact with anything dead, even the body of a close relative. Amos 2:11-12 describes permanent Nazirites among the Israelites as recipients of a special calling from Israel’s God. Amos also parallels their calling with that of the prophets, who lived together in community (cf. 2 Kgs/4 Kgdms 6:1-2). The Nazirite tradition continued into the New Testament period not only in the person of St. John the Forerunner who became the pattern for later Christian monasticism, but also directly, in members of the apostolic church in Jerusalem continuing to consecrate themselves as Nazirites (as in Acts 21:17-26).

The overarching purpose of the book of Judges is to show the descent of Israel, following the conquest under Joshua, into chaos and madness. Samson’s story comes at a point very close to the nadir of the descent. He is the last described judge, worse than all before, whom God uses despite himself. The closing chapters of Judges then describe the horror, violence, and civil war into which Israel fell after his time. All of this is with the purpose of demonstrating the necessity of Israel’s monarchy, specifically the monarchy of David (as the final chapters show how Benjamin, Saul’s tribe of origin, was complicit in the worst of Israel’s distress). We can see then that the pattern described in Judges and Samuel is paralleled in St. John the Forerunner and Jesus as Messiah, the son of David, albeit in an inverse way. Samson is a sort of dark forerunner to David’s reign. He is a type of antichrist.

In order to portray him in this light, the book of Judges describes Samson, from the beginning of its description of his adult life, in terms of sin, wickedness, and the violation of each of his vows in turn. His first action in the text is to dishonor and disobey his parents by marrying a Philistine woman, a violation of holiness and the Torah (14:1-3). On the way to visit her and set up the wedding feast, he kills a lion and then eats with his hands from its carcass, violating his vow against coming into contact with dead things (14:8-9). The feast is said to have taken place in a vineyard, violating his oath regarding the drinking of wine. His Philistine wife’s father, because Samson used the wedding feast to slaughter many of his countrymen, gives his daughter to another. Samson is enraged when he comes back to gratify himself sexually with her and is denied and Samson takes revenge by burning their fields (15:1-5). The Philistines retaliate by burning his wife and her father (v. 6). Samson then states that he is going to avenge himself, and slaughters 1,000 Philistines (v. 15). He does this, however, with the jawbone of a dead donkey. Just as he was unable to resist the passion of his hunger, so after the slaughter he becomes petulant with God, mirroring the grumbling of Israel in the wilderness, when unable to control his thirst (v. 18-19).

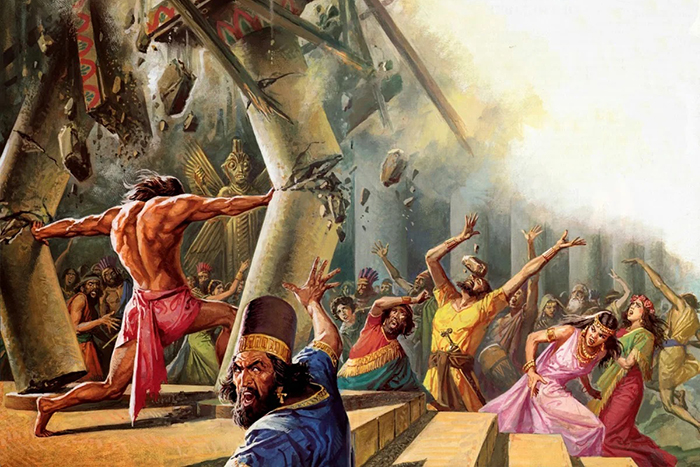

After a tryst with a prostitute (16:1), Samson begins a sexual relationship with another Gentile woman, Delilah. She betrays him after he reveals to her his Nazirite status (16:17). Here Samson reveals his level of understanding. He knows about the vows that have set him apart from his mother’s womb. This means that he has been violating them deliberately and unrepentantly. The means of repentance for the breaking of these vows had been set out in Numbers 6, and Samson has ignored them. Further, he knows that his source of strength, the Spirit, will depart from him if he breaks the one vow so far unbroken, that regarding his hair. Even being blinded and held prisoner does not bring Samson to repentance. In his final ‘prayer’ he requests from God no forgiveness and expresses no contrition. He asks only for one last burst of strength so that he can get revenge on the Philistines for what they did to him.

Samson, as judge of Israel, had been chosen to be a holy man, set apart by Yahweh the God of Israel to exemplify righteousness, holiness, and the fulfillment of God’s commandments. He was called upon to gratify not his own desires, but to live a life of asceticism pleasing to God. Instead, he broke every one of his vows and yielded to every pleasure of the flesh. He had been called as a judge to deliver Israel from the Philistines. God did this through him despite Samson’s disobedience. Rather than oppose them and free his people, Samson married one of them. His massive slaughters of Philistines were not carried out because they were the requirement of freeing the Israelites to serve Yahweh. Rather they were a series of personally motivated revenge killings over sleights against Samson. That this led to freedom for Israel was purely accidental, from Samson’s perspective.

Samson can, therefore, be seen as an icon of unbelieving Israel at their worst and their need for a king like David. St. John the Forerunner, likewise, is an icon of the believing remnant of Israel, awaiting the coming of the Messianic king. This polarity manifests itself in their respective ways of life. Samson’s path exemplifies a life which leads to death and destruction. St. John’s life exemplifies a life formed by the gospel which leads to eternal life. It is for this reason that St. John serves as the model for Christian monasticism as a pathway of, and leading to, holiness. Throughout the history of God’s people, from the earliest days of Israel to the present day, as a gift to the Church, God has given men and women called to monasticism. They are called to live a life of asceticism and strict obedience to all of the commandments of Christ. They are called to serve as an icon to the Church as a whole of repentance and obedience which lead to life.

Source: https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/wholecounsel/2019/04/11/samson-and-the-origins-of-monasticism/

P.S. Due to some online controversy, the team of the Catalog of Good Deeds must clarify that we do not support Father Stephen De Young’s idea that forefather Sampson is not a saint.